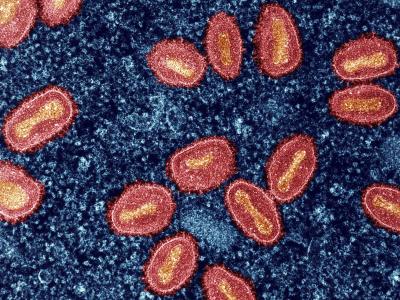

Sep 20, 2011 (CIDRAP News) – A study of preserved lung sections from 68 US soldiers who died in the 1918 influenza pandemic shows that cases from the spring and fall pandemic waves looked much the same and that there is no evidence of viral mutations that could readily explain why the fall wave was so lethal.

The study, led by Jeffery Taubenberger of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, showed the same pattern of damage to the respiratory tract as seen in severe flu cases in later pandemics, including 2009, and in severe seasonal flu. The authors also found evidence of secondary bacterial pneumonia—a common complication in severe flu cases today—in all 68 cases. The report was published online by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The 1918 pandemic is thought to have killed at least 50 million people worldwide, which has fueled speculation that the virus was uniquely virulent. Also, the record of a mild wave of flu in the spring or summer of 1918, depending on location, followed by a severe fall wave, has prompted speculation that the virus changed to become more virulent.

The new study doesn't support those speculations. Taubenberger's team found some evidence of a change in the virus's preference for binding to human as opposed to avian airway cells between the spring and fall waves, but they concluded that it doesn't explain the severity of the fall wave.

"Data from the case series do not support the hypothesis that high mortality in the 1918 pandemic resulted from unique pathogenic mechanisms," the report says. "The cause of extraordinarily high mortality in the 1918 pandemic appears not to be exclusively a factor of viral virulence, and thus remains to be fully elucidated."

Soldiers' lungs studied

The researchers studied lung-tissue blocks that were preserved in the National Tissue Repository of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. The 68 soldiers died between May 11 and Oct 24, 1918; 9 of them died between May 11 and Aug 18, a "prepandemic time period" when little flu activity was reported in the country. The other 59 died during the peak of the pandemic, from Sep 14 to Oct 24.

Microscopic examination showed similar changes in all the cases, including bronchitis, bronchiolitis, signs of primary viral pneumonia with alveolar damage, and "evidence of severe acute bacterial pneumonia," according to the report.

Flu virus antigens or viral RNA were found in the samples from 37 cases, including 4 from the prepandemic period, the report says. The distribution of viral antigens was similar in all the positive cases, and viral bronchitis was seen in all the cases for which bronchial tissue sections were available. The team found no differences in viral antigen presence in alveolar epithelial cells when they compared prepandemic and pandemic cases.

The researchers used polymerase chain reaction to detect viral RNA in 13 of 21 cases tested. In 11 of the 13, they determined the partial amino acid sequences for the part of the hemagglutinin protein that binds to host cells (receptor binding domain, or RBD). Three of four sequences from prepandemic cases pointed to a mixture of "avian-like" and "human-like" binding specificity, whereas seven of nine sequences from pandemic peak cases were suggestive of human-like binding specificity.

However, these differences were not associated with differences in microscopic findings or viral antigen distribution, leaving the significance of the finding unknown, the authors say.

"The data from this case series confirm that the clinical course and postmortem histopathological and microbiological findings in fatal 1918 pandemic influenza infections are not unique, and provide further evidence for the importance of secondary/concurrent bacterial pneumonias in fatal outcomes," the report states.

While commenting that their findings don't support the idea that the 1918 virus had "unique pathogenic mechanisms," the authors add a qualifier: "The data cannot, however, rule out effects of pathogenic host immune responses, or more rapid or higher titer viral growth, or of other important but unknown host or environmental cofactors."

They also observe that the cellular distribution of viral antigens in the cases "is remarkably similar to that observed in fatal 2009 pH1N1 pneumonia cases." Further, the pathology they found in the 1918 cases is "indistinguishable from that of influenza deaths in subsequent pandemics, including the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and in seasonal influenza deaths." Their view is that the 1918 pandemic, in its clinical and pathologic features, "differed in degree, but not in kind, from previous and subsequent pandemics."

Findings called exciting

Lone Simonsen, PhD, a Georgetown University epidemiologist who has studied the 1918 pandemic, said she was excited to learn of the identification of an H1N1 pandemic virus from the period before the pandemic took off in the fall.

"Over the last decade epidemiologists have identified and characterized a wave of what looked exactly like pandemic influenza in spring and summer of 1918 in the Americas, Europe, and Asia," Simonsen commented by e-mail. Some of these studies demonstrated that this first wave was marked by the same unusual age distribution of deaths as the fall wave, with young adults hit hardest.

"But finding a virus from the time before the pandemic really got going is like looking for a needle in a hundred-year-old haystack," she said. "Congratulations to Taubenberger and his colleagues for succeeding."

"I find it also very interesting that there was a genetic difference . . . in the virus's receptor binding site between the spring and autumn version of the 1918 pandemic virus," Simonsen added. Though the authors did not believe this mutation was associated with greater virulence, "perhaps it can help explain the close spacing (a few months) between pandemic waves in 1918" and also in the 2009 pandemic, she said.

Simonsen also commented that the severity of the fall wave of the pandemic might be related to genetic changes in other segments of the virus that have not yet been sequenced or to differences in host risks for bacterial infection between the two waves. "We will have to wait for answers on this important question," she said.

Sheng ZM, Chertow DS, Ambronggio X, et al. Autopsy series of 68 cases dying before and during the 1919 influenza pandemic peak. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2011 (early online publication) [Abstract]