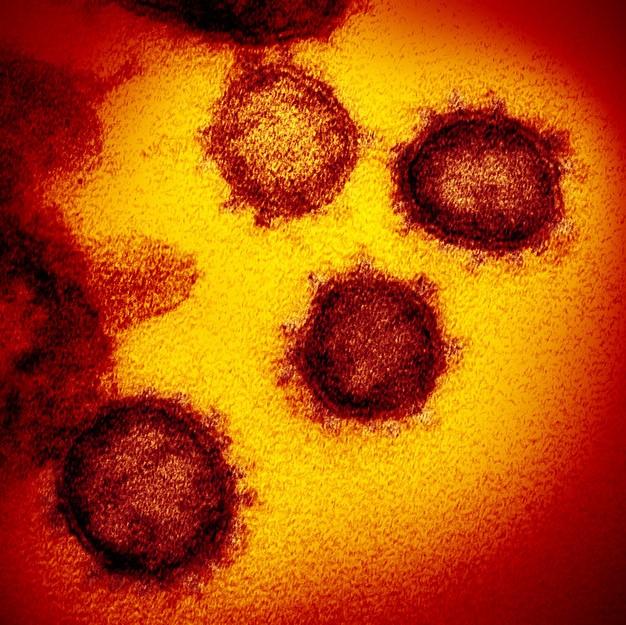

The new, highly mutated SARS-CoV-2 strain circulating in the United Kingdom is likely already sowing COVID-19 around the world, scientists say, fueling worries about recent surges that have swamped hospitals and whether it can thwart currently authorized vaccines.

The fact that the variant has developed 23 mutations in a matter of months is also reason for concern, top US experts say.

The variant, called B.1.1.7, has caused upwards of 50% of COVID-19 cases from Oct 5 and Dec 13 in the UK, mostly in people younger than 60 years, according to a Dec 21 World Health Organization report. An observed increase in the virus reproduction number (R0), the number of people that one infected person can infect—from 1.1 to 1.5—suggests that it is much more contagious than the previous "wild type" strain, the brief said.

With ongoing international travel between the UK and the United States, the mutated strain could already be circulating in the United States undetected, because less than a half percent of US virus genomes have been sequenced, but its presence hasn't been confirmed, according to a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) brief yesterday.

Stanley Perlman, MD, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology and pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, suspects that it is already in the United States. "I'd be surprised if it weren't," he said.

While many countries have closed themselves off to UK travelers, if the rapid spread of the new SARS-CoV-2 strain is being driven by its mutations and not simply epidemiologic factors, it will inevitably permeate borders, said Kristian Andersen, PhD, a professor in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. "We should not think that [a border closure] is going to prevent it from coming here," he said. "We can't prevent it. It will come here, and it will start spreading locally."

Will new vaccines be effective against it?

The new strain has prompted questions about whether current COVID-19 vaccines can fend it off. But as manufacturers rush to test their vaccines, Jesse Bloom, PhD, MPhil, associate professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, said that they are likely to have efficacy against the new variant.

While human coronavirus can gradually evolve to escape antibody-based immunity, and the UK variant may signify the start of this process, "this evolution happens over many years, and so should not cause immediate concern about the effectiveness of vaccines," he said.

Bloom said that scientists need to keep tabs on SARS-CoV-2 mutations to see if they are gradually evading antibody immunity, at which time it should be easy to update current vaccines. This is particularly true for mRNA-based formulations like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, in which it is relatively simple to change the spike protein sequence. These are the only two COVID vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

"But based on the time course of viral antigenic evolution … this is only going to be a problem over a many-year timeframe, which gives us as scientists plenty of time to respond," he said. "No one needs to worry that just a few mutations like the ones in the UK strain will make vaccines completely ineffective."

However, despite the likelihood of vaccine effectiveness against the new strain, Andersen said that, in addition to testing their vaccines, manufacturers need to prepare to revise, produce, and distribute any updated versions. "We shouldn't wait around to prove it before we act on it," he said. "We can't afford to be wrong about this."

23 mutations in a matter of months

Scientists, the CDC said in its brief, are trying to determine whether the mutations are responsible for the rapid spread (versus human behavior), affect severity of clinical illness, can evade diagnostic tests, affect natural or vaccine-induced immunity, are more or less likely to cause reinfection, or are less susceptible to treatments such as monoclonal antibodies.

But the very short time it took to develop more than 20 mutations, compared with the one or two additions or deletions expected to develop in that timeframe, along with its rapid change from a rare strain to a common one in England, is concerning, Perlman said. "I think what this teaches us is that we have to pay attention," he said. "Those kind of mutations don't arise easily."

A notable mutation in the variant is N501Y, located in the virus's spike protein, which is thought to enhance binding to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, the CDC brief said. Most of the individual mutations have been seen before, Perlman said, "but maybe they do a little better as a team."

Andersen called the highly mutated variant "entirely new territory," because it couldn't have evolved so quickly following the expected evolutionary process. "A separate process created this," he said.

That process, Andersen said, more likely occurred in a single chronically infected, immunodeficient or immunosuppressed COVID-19 patient treated with SARS-CoV-2–containing convalescent plasma, perhaps along with the antiviral drug remdesivir—a setting that can foster mutations.

Detection, mitigation measures

On Dec 14, the UK detected the SARS-CoV-2 variant through its robust, real-time SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance system, the COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium. In a Dec 20 risk assessment, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control said officials began an enhanced epidemiologic and virologic investigation after noting a pronounced increase in the 14-day case notification rate in Southeast England, from 100 cases per 100,000 in early October to 400 cases per 100,000 in December.

Sequencing of virus samples in Kent, the area most affected, indicated that the rise occurred at the same time as the emergence of the variant in November, when the country was in a partial lockdown amid Europe's second surge. But the geographic origin of the UK variant is unknown, Perlman said. "Amplification has  been noted in London, but it doesn't mean it started in London," he said.

been noted in London, but it doesn't mean it started in London," he said.

The new strain has also recently been identified in other European countries, such as the Netherlands, Italy, Iceland, and Denmark, as well as in Australia. Another highly mutated, rapidly spreading SARS-CoV-2 variant, unrelated to the UK variant but with the same N501Y mutation, among others, came to light in South Africa just days after the UK's variant was identified. That strain has been found in up to 90% of patient samples that underwent genetic analysis since mid-November, the New York Times reported on Dec 20.

In the past week, Britain has implemented the country's strictest lockdown since March, closing its borders, resulting in massive transportation disruptions. Following suit, other countries in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and North America (Canada, but not the United States) have been closing their borders to UK travelers in an attempt to stave off the mutated coronavirus.

Urgent need for better US surveillance

The UK's detection of the virus variant through its genomic surveillance system points to the need for a similar federal program in the United States, Andersen said. "It shows the incredible power and the necessity of having a really robust surveillance system, especially as the United States rolls out vaccines," he said. "Importantly, such a program would also enable [the United States] to detect what the UK just did with these mutations."

Smaller initiatives have been popping up around the country, such as the CDC's SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing for Public Health Emergency Response, Epidemiology, and Surveillance (SPHERES), according to the CDC brief. The program was launched in November but won't be fully operational until January.

Perlman agreed that close monitoring will be key as SARS-CoV-2 and its variants continue to change over time. "Whether it becomes a big deal or not, we don't know," he said. "The main point is that we have to be vigilant, but there's nothing there that should scare people."