Federal officials have beefed up the nation's Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) with antibiotics to protect Americans in future anthrax attacks and public health plans are set for their distribution, but the public may not be willing to take the drugs, a new poll found.

To get a handle on perceptions that could help public health departments craft messages that encourage more people to come to point-of-dispensing (POD) sites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) partnered with the Harvard Opinion Research Program at the Harvard School of Public Health.

The goal is to assess how the public might respond to an inhalation anthrax attack scenario. Experts shared the findings of this joint effort today in a CDC Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity (COCA) call and webinar.

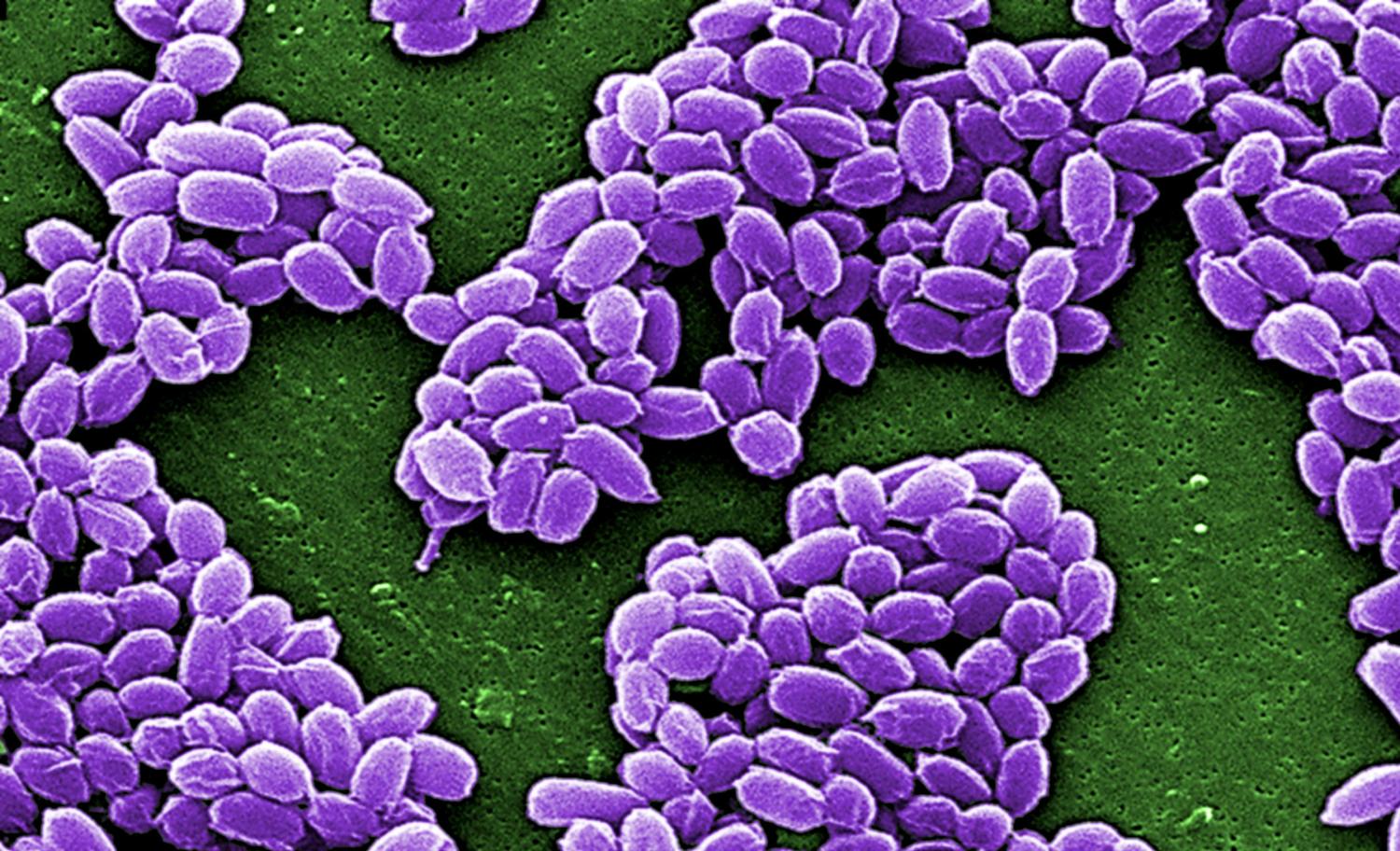

In an anthrax attack, federal response plans call for treating those at risk of Bacillus anthracis spore exposure with a 60-day course of antibiotics, and also offering three doses of anthrax vaccine for longer-term protection against late-germinating spores.

Laura Ross, PhD, lead health communication specialist in the division of state and local readiness with the CDC's Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, told participants that health departments face a tall task in getting the medication to the public within the recommended 48-hour time frame, including the step of getting the public to come to the PODs.

To mobilize people, health officials needs to gauge what knowledge gaps and misperceptions are barriers to people showing up to get—and take—the antibiotics, she said. Ross said, for example, people might leave their jurisdictions if an attack occurs nearby, or they might have resentments if companies or institutions assist with response efforts by dispensing the medications only to their employees and employees' family members.

The Harvard team conducted three survey rounds, which began in 2009, to help federal officials answer the questions. Gillian SteelFisher, PhD, MSc, presented new information from the third survey round, conducted from Dec 17, 2012, to Jan 11, 2013. She said the telephone (landline and cell phone) survey polled 1,509 nationally representative respondents and oversampled parents to better assess pediatric issues.

The survey walked respondents through a mockup of a possible anthrax attack in their area that resulted in illnesses and deaths, then asked them several questions to assess knowledge of preventing illness after possible exposure.

Though most (62%) were familiar with the term "inhalational anthrax," nearly half (46%) had missing information or misperceptions about whether the condition is contagious. SteelFisher said this finding shows that messaging efforts need to correct misinformation. "People may be reluctant to stand close to other people and stand in line at PODs," she said.

The vast majority (83%) of respondents said they'd be very or somewhat worried about getting sick or dying, consistent with other data, but 40% said they'd likely or definitely leave their area if there were anthrax cases in their town. SteelFisher said that reaction would make it more difficult for health departments to get people to PODs.

The public had positive impressions about the safety and effectiveness of the drugs but not a lot of confidence in the government's ability to supply the antibiotics or for local health officials to deliver them. SteelFisher said the numbers suggest that people might be vulnerable to rumors, and that messages can be designed, for example, to reassure people about the supply and show that POD crowds are peaceful and secure.

An overarching question about how likely the public would be to follow recommendations to pick up the pills from dispensing sites showed that 69% would be very likely and 21% would be somewhat likely. "Those are pretty good numbers," she said.

The poll found that 8% of adults and 14% of children would have trouble swallowing a pill, so liquid suspension and pill-crushing directions would be needed to help some people take their medication, SteelFisher said.

Overall, SteelFisher said the survey reveals the public saying they'd likely pick up the medications, but at the same time weighing the upsides against the risks of getting sick.

Info from the webinar and full survey findings are available in a slide presentation posted on CDC's COCA Web site.

See also:

Jul 23 CDC COCA presentation slides