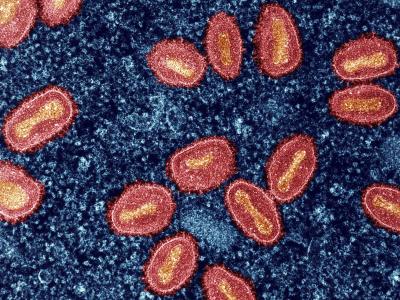

In a pair of studies that provide more insight on the link between Zika infection and microcephaly, Finnish researchers today described early imaging and lab findings that might help with clinical diagnosis, while a team from California offered a possible explanation for how the virus targets neural stem cells in developing fetuses.

In other news, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the availability of a new test for screening blood donations for Zika virus, Brazil added about 100 more cases to its suspected microcephaly total, and key experts published new Zika virus reviews.

Zika in fetal brain tissue

In a New England Journal of Medicine report today, Finnish researchers described their investigation into brain abnormalities detected in the fetus of a 33-year-old Finnish woman who was infected with the virus while on a trip to Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize in November 2015 while she was 11 weeks pregnant.

Her symptoms began 1 day after she returned to her home in Washington, D.C., and serology tests 4 weeks later on a trip to visit her home country were positive for recent Zika virus infection. Based on her test results, the woman asked for a more thorough assessment of the fetus.

Fetal ultrasound at 19 weeks showed serious brain abnormalities, but no calcifications. Earlier images at 13, 16, and 17 weeks gestation showed no sign of microcephaly, but an image taken at 20 weeks suggested a drop in head circumference from the 47th percentile at 16 weeks to the 24th at 20 weeks.

Clinicians saw more serious abnormalities on fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 20 weeks, and because of the grave prognosis, the woman terminated her pregnancy at 21 weeks gestation.

To further investigate the findings, researchers conducted more Zika tests on the woman and her spouse, who had also been infected during travel, and did immunohistochemical tests and microscopic examination on fetal brain tissue.

They detected Zika RNA in the woman's blood samples 4 and 10 weeks after her symptom onset, but not after delivery. Given that viremia lasted longer than typically seen in nonpregnant people with Zika infections, the researchers suspected that Zika virus in the placenta or fetus might have caused the woman's levels to persist, suggesting a possible role for Zika testing in pregnant women beyond the 1-week-after-symptom-onsest mark.

The investigators said Zika dynamics in pregnant women aren't well understood and require further study.

Reductions in brain volume seen in the ultrasound series would have likely met the microcephaly criteria, they noted. The lag time between fetal Zika infection and brain abnormalities means ultrasound studies might be falsely reassuring and delay clinical decisions, and fetal brain MRI might be more sensitive and speed the identification of problems, the team wrote.

Investigators isolated Zika virus RNA from the fetal brain and several fetal organs, but they were able to isolate infectious virus from brain tissue only, which they said shows a neurotropic pattern suggested by other recent studies.

Potential neural stem cell portal

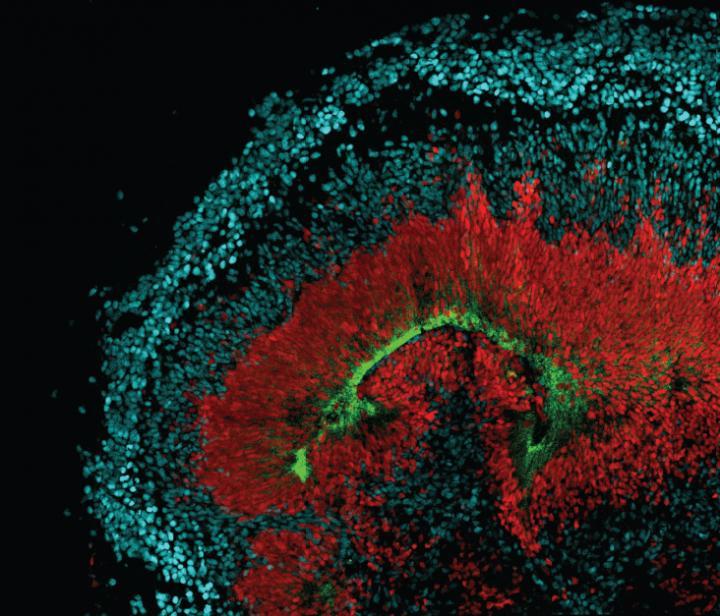

In the study of neural stem cells—which are present only during the second pregnancy trimester—researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, knew from earlier studies that other flaviviruses seem to use the AXL surface receptor to enter cells and cause infection. The study appears today in an early online edition of Cell Stem Cell.

Using single-cell RNA sequencing, the team looked for the AXL receptor in several different brain cell specimens, including those from mice, ferrets, human stem cells, and developing brain tissue in humans.

Tests on each sample showed expression of AXL by radial glial cells, the source of cell types that build the cerebral cortex. Next the researchers conducted immunohistochemistry tests in the developing tissues and organs to see where AXL receptors were most likely to be found on neural stem cells. They found that the receptors gravitate to sites where neural progenitors connect with cerebrospinal fluid or blood vessels.

The researchers said the location would allow Zika virus easy access to vulnerable host cells.

Also, the team found similar disruption in retinal stem cells, which they said would be consistent with eye problems that have also been noted in babies with Zika-associated microcephaly.

Arnold Kriegstein, MD, PhD, senior author, said in a Cell Press media release, "While by no means a full explanation, we believe that the expression of AXL by these cell types is an important clue for how the Zika virus is able to produce such devastating cases of microcephaly, and it fits very nicely with the evidence that's available."

He added that AXL isn't the only receptor linked to Zika infection, so the next step will be show that blocking it can prevent infection, which might pave the way for a treatment for women that would block Zika virus from the developing fetus.

Why Zika virus is so virulent in the developing brain is still a mystery, Kriegstein said. "It could be that the virus travels more easily though the placental-fetal barrier or that the virus enters cells more readily than [with] related infections."

Other developments

- The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that an experimental test to screen blood donations for Zika virus is now available and may be used under an investigational new drug application (IND) in local transmission areas, according to a statement today.

- Brazil reported 105 more suspected microcephaly cases last week, according to the health ministry's weekly update, translated and posted by Avian Flu Diary, an infectious disease blog. The number was down from the last several weeks. So far 944 cases have been confirmed overall, and health officials are still investigating 4,291 suspected ones.

- Experts published two comprehensive Zika virus reviews today in two different journals. A team from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published theirs in the New England Journal of Medicine, and a duo of infectious disease specialists, one from French Polynesia and the other based at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, published theirs in Clinical Microbiology Reviews.

See also:

Mar 30 N Engl J Med report

Mar 30 Cell Stem Cell study

Mar 30 Cell Press press release

Mar 4 CIDRAP News story "Pair of studies add weight to link between Zika and birth defects"