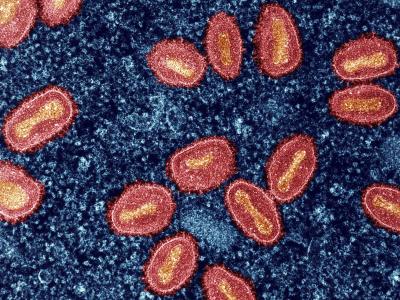

Diarrhea was the main symptom that a South Korean man experienced upon returning from a business stay in Kuwait, which didn't trigger isolation for possible MERS-CoV until further work-up at the hospital, raising questions about whether the case definition should be revised to include diarrhea.

Doctors from South Korea described the man's symptoms, work-up, and care in a Dec 31 report in the Journal of Korean Medical Science. The man's illness, reported in early September, was South Korea's second imported MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus) case.

The country's first one in 2015 sparked an outbreak that sickened 186 people, 36 of them fatally. The earlier event showed how a single illness, which often has nonspecific symptoms making it difficult to detect, can trigger a massive outbreak and led countries and hospitals to shore up their screening criteria, especially among people traveling to and from Middle East destinations.

With the second case, however, no related infections in South Korea were reported.

Though respiratory symptoms are the major clinical feature of MERS-CoV, the authors note that gastrointestinal symptoms have been reported in up to 30% of patients.

No fever, few respiratory symptoms

According to the report, the man arrived in Kuwait on Aug 16 and developed watery diarrhea on Aug 28. He didn't have a fever and had few respiratory symptoms, but he got weaker and his gastrointestinal symptoms continued, leading him to visit a local health clinic in Kuwait twice—on Sep 4 and Sep 6.

He flew back to South Korea on Sep 7 as his symptoms worsened. When he arrived, he reported diarrhea and weakness and went directly to the hospital by taxi.

At the emergency department (ED), he had a fever of 100.9°F (38.3°C), and chest x-ray showed bilateral interstitial infiltration. The ED doctors suspected MERS-CoV, and the patient was placed in an isolation unit the next day. A sputum sample confirmed MERS-CoV infection, but tests on samples from serum, a nasopharyngeal swab, and stool samples were all negative for the virus.

The man was treated with empirical antibiotics, but he did not receive any antiviral treatment.

He experienced dyspnea and hypoxemia, but over the next 2 days his diarrhea and other symptoms were improving. Follow-up MERS-CoV testing on Sep 14 and 15 were negative, and the patient was discharged from the hospital on Sep 22 on day 25 of his illness.

An investigation into the source of his illness in Kuwait didn't turn up any risk factors, such as visiting a camel farm or consuming camel milk or other products. The authors wrote that although the patient may have contracted the virus at the clinic, he already had leukopenia and thrombocytopenia during those visits, based on the results of blood tests there.

"Considering the shortest incubation period of 2 days, we can safely say that he had already been infected with MERS-CoV when he visited the clinic, and diarrhea was a presenting symptom of MERS in this patient," the authors wrote.

They added that less than half of Saudi MERS-CoV patients have a history of exposure to camels, and infections can occur even in patients who don't have a history of exposure to camels or camel products.

Also, they said the Korean man's respiratory features on imaging in the absence of symptoms builds the case for ordering chest radiographs, even if respiratory symptoms are mild or absent.

Should case definition be revised?

The researchers pointed out that, with diarrhea and few respiratory symptoms, the man didn't meet the MERS-CoV case definition when he arrived at the airport, and the quarantine office didn't isolate him.

His clinical course raises questions about whether the case definition should be revised to include diarrhea symptoms, they wrote. However, they noted that the answer may depend on whether MERS-CoV is excreted in stool and is transmissible by that route, though no fecal transmission has been reported so far.

Also, they said that diarrhea is a common, nonspecific symptom and that many patients with traveler's diarrhea might undergo unneeded screening tests. "Therefore, inclusion of diarrhea symptom in the case definition for MERS-CoV surveillance requires more data and ensuring evidence," they wrote.

In a related editorial in the same issue, two experts from Seoul wrote that the man's lack of fever, his diarrhea, and few respiratory symptoms at the airport didn't meet the criteria of a patient under investigation (PUI) as defined by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and that the second imported case triggered discussions about whether or not the criteria should include patients with diarrhea and no respiratory symptoms.

They wrote that the case shows that MERS-CoV can be imported from countries other than Saudi Arabia and involve atypical presentations. Though the two recognized concerns about excessive testing and isolation if diarrhea is added to the case criteria, they noted that during the response to the most recent imported case, a Seoul hospital modified its criteria for MERS-CoV testing to include patients with diarrhea and a Middle East travel history. Sixteen were tested, but none because of diarrhea.

"Therefore, addition of diarrhea in clinical features indicating PUI possibly makes surveillance for MERS infections more thorough with an affordable burden," they wrote, adding that better PUI criteria would tighten quarantine surveillance.

See also:

Dec 31, 2018, J Korean Med Sci study

Dec 31, 2018, J Korean Med Sci editorial

Sep 12, 2018, CIDRAP News story "WHO details South Korea's imported MERS case"