Young children with pneumonia were 5 times more likely to die if they had bacteremia and 17 times more likely to die if they had antibiotic-resistant bacteremia than if they had no bacteremia, according to a Bangladesh-based study late last week in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

"If COVID-19 was a tsunami, then emerging antibiotic resistance is like a rising flood water. And it's kids in Bangladesh who are already going under," said co-first author Jason Harris, MD, MPH, in a Massachusetts General Hospital press release. "These kids are already dying early because of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, from what would be a routine infection in other parts of the world."

Pneumonia killed more than 800,000 children under age 5 in 2017, according to the World Health Organization, and the study researchers say that pneumonia is the third leading cause of sepsis in this age-group. Bacteremia is the presence of bacteria in the blood.

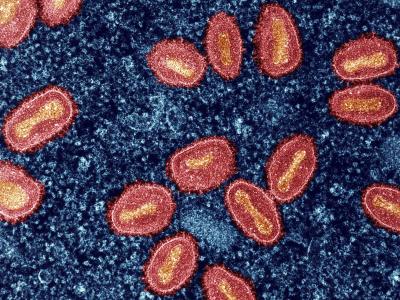

Most positive cultures were gram-negative

Out of the 4,007 pneumonia patients 5 years or younger meeting the criteria for clinical and radiographic pneumonia admitted to a Bangladeshi hospital (median age, 7.6 to 7.95 months), 45% (1,814) had blood cultures, of which 108 (6%) were positive.

Children were more likely to have a positive blood culture if they were severely underweight (up to 3 standard deviations by weight-by-age), and children with bacteremia had lower mean hemoglobin levels (9.8 vs 10.3 grams per deciliter) and were more prone to severe sepsis and respiratory failure than those without.

Most positive cultures (83 [77%]) showed gram-negative pathogens, including Pseudomonas (22) and Enterobacteriaceae (46, including Escherichia coli [17], Salmonella enterica [14], and Klebsiella pneumoniae [11]). Gram-positive pathogens were most commonly Pneumococcus (7) and Staphylococcus aureus (6).

"With the exception of K pneumoniae, these pathogens are typically not associated with a primary respiratory infection, which suggests that young children with both clinical and radiographic evidence of pneumonia may have other or additional underlying source(s) of illness, particularly in a population where concomitant malnourishment and diarrheal illness are common," the researchers note.

Twelve of 30 E coli, K pneumoniae, and Enterobacter (40%) isolates were resistant to all routinely used empiric antibiotics, with ciprofloxacin resistance as a proxy for levofloxacin resistance. Four of five Enterococcus samples were resistant to both ampicillin and ciprofloxacin. Most other bacteria, however, did not display multidrug resistance; only two of 20 Pseudomonas showed resistance against ceftazidime.

The researchers acknowledge that the cause of infection in the children with bacteremia is not generalizable to those who had no blood culture or a negative blood culture. Still, they write, "It is possible that some of these antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, even in the absence of detectable bacteremia, significantly contribute to the disease burden in this group of children."

Mortality linked with bacteremia, resistance

During hospitalization, 186 children (4.6%) died, and higher mortality risk was associated with those who had bacteremia or antibiotic-resistant bacteremia. Children with gram-negative or gram-positive bacteremia had five times the mortality risk of children without bacteremia (odds ratios [ORs], 5.2 and 5.0, respectively). Antibiotic resistance further increased mortality risk: Resistance to first-line antibiotics ampicillin and gentamicin resulted in a 9.6-fold risk, and resistance to all first- and second-line therapies carried a 17.3-fold risk.

Overall, children who had bacteremia resistance to all first- and second-line therapies had a higher risk of death than those who had bacteremia sensitive to at least one antibiotic. For instance, the researchers found that 8 of 12 children with resistant E coli, K pneumoniae, or Enterobacter died, compared with 5 of 18 who had sensitive bacteremia (OR, 5.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1 to 25.3).

"Despite care in a tertiary setting with expertise in the treatment of critically ill malnourished children, 9% of children admitted with pneumonia who had a blood culture obtained died before discharge from the hospital, including 30% of children with bacteremia and pneumonia," the researchers write.

While the study methods did not take into account preadmission antibiotic usage, the researchers say that Bangladesh people tend to self-prescribe antibiotics for health conditions such as dysentery, cold, cough, and fever, which can increase antibiotic resistance.

"We may be able to reduce this emerging bacterial resistance by improving antibiotic stewardship, particularly in the outpatient setting," said senior author Tahmeed Ahmed, PhD, executive director of the Bangladeshi hospital featured in the study, in the press release. He added that other areas of improvement include increasing access to diagnostic testing for bacterial infections and expanding access to clean water and better sanitation.