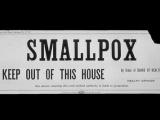

National Institutes of Health (NIH) employees discovered old vials that appear to contain smallpox in an unused lab area and have turned them over to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for containment and testing, federal officials announced today.

The vials, labeled "variola," appear to date from the 1950s and were found in an unused part of a storage room in a lab on the NIH's Bethesda campus that was transferred to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1972, the CDC said in a statement today. Scientists found the vials while getting ready for the lab to move to the FDA's main campus in Silver Spring, Md.

They immediately secured the samples in a registered select-agent lab in Bethesda, Md., and yesterday federal officials and law enforcement agencies moved them to the CDC's biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) lab in Atlanta.

Testing for live virus

So far there is no sign that the samples were breached, and no exposure risks to lab workers or the public have been found, the CDC said.

Scientists at the BSL-4 lab detected variola virus DNA, and further tests are under way to see if the material in the vials contains live virus. Results won't be known for about 2 weeks, and lab workers will destroy the samples after testing.

The CDC said it has notified the World Health Organization (WHO), which oversees an international agreement on the security and safety of smallpox virus samples at two designated repositories: one at the CDC in Atlanta and one in Novosibirsk, Russia.

The WHO has been asked to join the investigation and will witness the destruction of the materials, based on protocols that are part of the international agreement. Federal agencies are piecing together how the samples were originally prepared and stored in the FDA lab.

How big a threat?

Michael T. Osterholm, PhD, MPH, said an accidental release would be worrisome, but, compared with other pathogens such as influenza, public health officials could easily contain one with vaccination and antivirals. Osterholm is director of the University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, publisher of CIDRAP News

He said there may well be other similar samples languishing in old freezers in labs—like old trunks in attics—and scientists may be uncovering more vials in the future. However, he said the bigger concern is intentional use of the smallpox virus, which the US government considers a Tier 1 select agent, alongside other dangerous pathogens such as the Ebola virus and Bacillus anthracis, which causes anthrax.

Though it's unlikely that terrorists have their sights on old smallpox samples, the event is a reminder that genetic tools that have the potential to someday re-create viruses such as variola are becoming more sophisticated, Osterholm said.

Smallpox eradication expert weighs in

D. A. Henderson, MD, MPH, who led the global smallpox eradication campaign in the 1960s and 1970s, said he is familiar with the NIH lab—known as the Division of Biological Standards back then—and what the conditions were like in the 1950s when the samples likely went into storage. He is currently a distinguished scholar at the UPMC Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

The only protection lab workers had for working with the virus back then was vaccination, Henderson said. He said indications suggest the vials might contain freeze-dried samples, which could suggest they were used for developing standards for the vaccine.

"One of the questions is, 'Is it dead or not?' We don't know," he said. However, he said survival chances are slim, because the viruses would have probably deteriorated unless they were stored for all those decades in an oxygen-free state.

Also, keeping smallpox specimens in the cold for prolonged periods might not bode well for their survival, Henderson said, based on difficulties scientists have had isolating the virus from bodies found in tundra areas and the problems Afghani "variolators" described many decades ago about keeping the scab samples alive over the winter in the mountains.

(Variolators exposed people to smallpox on purpose using pus or scabs as a way to promote immunity to the disease.)

Henderson said that at the time the samples were stored, virologists kept all kinds of specimens in freezers, and sometimes researchers didn't clean them out before moving on to other labs.

A high-profile lab accident involving smallpox work was one of the events that led to lab safety regulations for dangerous pathogens, he said.

Henderson said the accident at the University of Birmingham Medical School in 1978 killed a woman who worked on a different floor of the lab. The scientist who led the smallpox work in the lab, despondent over the safety lapses that infected the woman, committed suicide after the worker, and then the worker's mother, got sick with the disease.

The woman was the last person known to have died from smallpox. Henderson said the events caught the attention of the world's health ministers, who were in the process of introducing regulations for pathogen labs.

See also:

Jul 8 CDC press release

CIDRAP comprehensive overview on smallpox