Mar 24, 2004 (CIDRAP News) The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) says it sees a lower risk for further cases of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in the United States than was described recently by an international panel of experts on the disease.

The international panel said in early February that other BSE-infected cattle, besides the one found in Washington state in December, probably were imported into the United States from Canada and rendered into cattle feed, making it likely that more cases of the disease exist in American herds. The USDA had commissioned the panel to review the US response to the BSE case.

In a response to the panel's Feb 4 report, the USDA said today that other analyses, including its own assessment last fall and another by a group at Harvard University, "indicate that BSE is likely to be found in the U.S. at very low incidence, if at all. Further, it is extremely unlikely to be amplified in animal feeds while mitigation strategies that are in effect reduce the risk in the human food supply to a nearly negligible level."

The statement, posted today on the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Web site, continues, "If such amplification had occurred, it is likely that at least some affected animals in the United States, if they exist, would have clinically observable signs of BSE and would have been reported as sick animals even if the cause of their disorder was unknown at the time."

The expert panel, according to the USDA, assumed that the two North American BSE cases represent "a widespread epidemic rather than a small clustered epidemic." However, says the USDA, "There is evidence to indicate that the two North American cases are a clustered epidemic. The epidemiologic investigations suggest that the cattle were possibly linked by a common feed supplier."

The statement adds that the USDA's expanded BSE surveillance program, announced Mar 15, will help determine which view is correct. The department said that over the next 12 to 18 months it plans to test as many as possible of the estimated 446,000 cattle currently at increased risk for BSE.

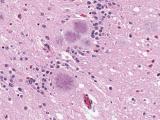

Cattle contract BSE by eating feed containing infectious material from cattle or other ruminant (cud-chewing) animals. Cattle meat-and-bone meal (MBM) was used as a cattle feed supplement in the United States and Canada until the practice was banned in 1997 to prevent BSE. Eating meat products from infected cattle is believed to be the cause of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), a fatal human brain disease similar to BSE.

The USDA statement takes issue with the expert panel on the effectiveness of the 1997 feed ban. The panel said that in the early years of Europe's BSE crisis, a similar feed ban failed to prevent the continued spread of the disease, probably because cattle feed was accidentally contaminated (cross-contaminated) with feed that was intended for other animals and contained cattle MBM. The experts suggested that the same thing could happen in the United States.

But the USDA says the situation in Europe 10 years ago was very different from the current North American situation in that many thousands of European cattle were infected, resulting in a higher risk of feed contamination. "The major source of infection in the European epidemic was ruminant-origin MBM, not cross contamination," the USDA states.

The document also notes that the Food and Drug Administration, which regulates animal feed, has proposed some changes in the feed ban, including a ban on the use of blood products, restaurant food waste, and poultry litter in cattle feed.

The USDA says it agrees with many of the expert panel's findings and recommendations, such as the advice to develop a national cattle tracking and identification system. However, the agency differs with the panel on a few details.

After the BSE case was discovered last December, the USDA banned "specified risk materials" (SRMs)tissues more likely to carry the BSE agent in infected cattlefrom the human food supply. SRMs were defined as the brain, skull, eyes, trigeminal ganglia, spinal cord, dorsal root ganglia, and vertebral column of cattle over 30 months old, plus the small intestine and tonsils of all cattle. But the expert panel recommended that the entire intestine of all cattle and the brain, spinal cord, skull, and vertebral column from cattle older than 12 months be banned from the food supply, unless increased surveillance shows a minimal risk of BSE in the United States.

The USDA says scientific evidence doesn't warrant removing the entire intestinal tract. As for removing other SRMs from cattle between 12 and 30 months old, the department says it will re-evaluate the question after the expanded surveillance program is completed.

The panel also recommended a ban on processing of cattle skulls and vertebral columns with mechanical systems ("mechanically recovered meat" [MRM] and "advanced meat recovery" [AMR]). Further, the group suggested that USDA consider banning the use of all "mechanical tissue processing methods" in producing beef for human food, because it is difficult to completely separate the skull and vertebral column (with associated nerve tissue) from the rest of the carcass.

In response, the USDA says it has already banned using "mechanically separated beef" for human food and has banned AMR product that contains nerve tissue. In addition, it has banned the use of skulls and vertebral columns from cattle older than 30 months and has imposed several supporting rules. "With these measures in place, a total ban on beef produced through AMR systems is not necessary," the statement says.

In other comments, the USDA says the expert panel, since it released its report, has reviewed the new BSE surveillance plan and found it to be "comprehensive and scientifically based."

See also:

Feb 4, 2004, CIDRAP News story, "USDA review panel urges tightening BSE rules"