A comprehensive look at last summer’s surge in variant H3N2 (H3N2v) infections found that most people who got sick were exposed to pigs at fairs, some for multiple days, and that younger children and those with underlying medical conditions were at greatest risk for more severe infections.

However, experts are still left with questions about how swine influenza viruses jump to humans, leaving gaps in knowledge about how to best protect people—and pigs—from new flu viruses.

The study was led by flu experts at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and involved collaborators from the animal health sector and health officials from 10 states that reported H3N2v cases last summer. The team published its findings yesterday in an early online release from Clinical Infectious Diseases.

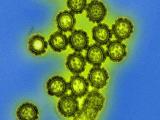

H3N2v first emerged in the summer of 2011, sickening 13 people in the months that followed. It is a swine H3N2 virus that contains the matrix (M) gene of the 2009 H1N1 virus, a feature that scientists suspect could enhance transmissibility and that raised concerns about pandemic potential. During the summer of 2012, the number of H3N2v infections skyrocketed, totaling 306 from July through September.

Researchers analyzed cases reported last summer between Jul 9 and Sep 7. When health officials first noted the rise in H3N2v cases, the CDC asked medical providers to increase sample collection in patients who sought treatment for flu-like illness after being at fairs or in areas where other cases had been found.

Health officials used a standard investigation form to collect clinical information on the cases and looked for possible cases of human-to-human infection. Cases were confirmed with RT-PCR, and researchers conducted full or partial genome sequencing on a subset of the viruses.

Younger age, swine exposure stand out

The location and timing of the infections seem to follow swine density and fair dates. Except for Hawaii, states reporting cases were in the upper quartile of the nation for swine density per county. More than 80% of the cases were detected in Ohio and Indiana. The number of agricultural fairs peaked the week of Jul 22, about a week before the epidemic curve peaked.

Most cases were associated with direct (69%) or indirect (26%) contact with swine, and most exposures were at agricultural fairs. The incubation period for patients with available information was 2.91 days.

Nearly all patients were children younger than 18, and the median age was 7 years. However, the median age of hospitalized patients trended even younger at 5 years. Sixteen people were hospitalized for their infections, including 11 who were very young or had one or more underlying health conditions.

The only death reported in the outbreak was in a 61-year-old woman who had multiple chronic medical problems.

Person-to-person transmission was identified in 15 cases, all in children younger than 10, but the team found no evidence that the virus passed steadily or easily to other people.

Laboratory analysis of the virus samples showed that all were nearly identical and all were susceptible to neuraminidase inhibitors.

Infections were mostly self-limiting, marked by fever, coughing, and fatigue. The team reported that one notable finding was that about a quarter of the patients reported eye redness or irritation, which isn’t usually seen with seasonal flu infection but has been known to occur in H7 avian influenza infections and in children who were hospitalized with 2009 H1N1 influenza. For now, it’s unclear if conjunctivitis is an indicator of H3N2v infection, the researchers said.

Direct contact with swine on multiple days before getting sick stood out as a distinguishing characteristic of patients in the outbreak, the team wrote. Nearly two thirds had swine exposure on more than one day, and more than a fourth had daily exposure the week before they got sick.

Though swine exposure has been linked to variant influenza viruses before, detailed information about the outbreak setting and the duration of exposure hasn’t been available before, especially for such a large number of cases, they added. Among more recent H3N2v and H1N1v reports, only 42% of patients reported direct contact with pigs.

Though the pace of H3N2v infections has slowed, that they still occur serves as a reminder that fair managers, swine exhibitors, and attendees need to be aware of the risks, especially to those in vulnerable groups, the team wrote. They also said the outbreak highlights the need for continued collaboration between animal and public health agencies in tracking and responding to novel influenza A viruses.

A good epi picture, but questions remain

In an accompanying editorial, two infectious disease experts—one from the United States and one from China—commended the authors and the interagency work that went into producing the report. The authors are Gregory Gray, MD, MPH, professor and chair of the Department of Environmental and Global Health in the College of Public Health and Health Professions at the University of Florida in Gainesville, and Wu-Chun Cao, MD, PhD, from the State Key Laboratory of Pathogen and Biosecurity in Beijing.

Agricultural fairs are a known risk factor for swine flu virus infections in humans, but now the epidemiologic data have never been stronger or more geographically widespread, the two experts wrote.

However, they pointed out that despite the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and now the H3N2v outbreak, scientists still don’t have a clear understanding of the dynamic ecology of swine flu-like viruses that circulate freely between pigs and people. “Instead we must often wait for humans to serve as sentinels through their infection with such novel viruses,” the two wrote.

They detailed several challenges that make studying the relationship difficult, including possible economic drawbacks for swine producers.

Doing the necessary studies, especially multidisciplinary ones that look at large commercial farms as well as small hobby farms where fair pigs are raised, could provide clues on how to reduce the risk of cross-species flu transmission, they wrote. For example, they noted that recent studies have found evidence of aerosol swine flu spread, which may make current biosecurity steps obsolete.

China could be a promising setting for much-needed collaborative research involving human and animal health specialists, because the country is home to almost half of the world’s pork production, large government-owned farms wouldn’t be threatened by research studies, and the nation has a strong scientific and lab network to support the work, the authors suggest.

Why a dramatic drop in cases?

So far this year only 18 H3N2v infections have been detected, all of them in people who were exposed to pigs at fairs. Health officials don’t yet know what factors led to the dramatic drop in cases.

When asked to share his thoughts on the reasons for the drop, Gray told CIDRAP News that experts can only speculate, because no data are available to the public on what swine flu strains are circulating in US pigs, a problem he and his coauthor noted in the editorial.

Possibilities might be that CDC and US Department of Agriculture efforts at swine shows are working or that newer swine flu strains that cause fewer human illnesses have edged out H3N2v in US pigs, Gray said. Other possibilities could be that fewer swine show participants are seeking testing or that fewer people are taking part in swine shows, he added.

Jhung MA, Epperson S, Biggerstaff M, et al. Outbreak of variant influenza A (H3N2v) virus in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2013 Sep 24 [Abstract]

Gray GC, Cao WC. Variant influenza A H3N2 virus: looking through a glass, darkly. (Editorial) Clin Infect Dis 2013 Sep 24 [Link]