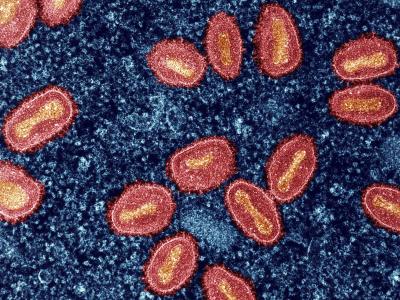

Jun 22, 2004 (CIDRAP News) The possibility of a smallpox outbreak highlights a key threat to America's public health system: What if a person needs a vaccine but there is no nurse to give the shot?

America's growing shortage of qualified public health workers could undermine terrorism preparedness, according to a recent report from the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO).

The absence of employees is most keenly felt in public health nursing, epidemiology, laboratory science, and environmental health, the association found. The report, "State Public Health Employee Worker Shortage Report: A Civil Service Recruitment and Retention Crisis," drew results from a 2003 survey of senior state and territorial health officials done in conjunction with the Council of State Governments and the National Association of State Personnel Executives. All states, territories, and the District of Columbia were invited to participate; 37 responded.

"We've got more job openings and no people to fill them. And it's going to get worse," Paula A. Steib, ASTHO communications director, told CIDRAP News in summarizing the findings.

The report found that the public health workforce is aging rapidly, with an average age of nearly 47; retiring at an expected average rate of 24% in the next 5 years; stretching to cover job vacancies of up to 20% in some states; and leaving public health jobs at a high rate (average, 14% per year among the 28 states responding to this question).

Employees quit over low salaries, minimal advancement opportunities, and attractive private-sector job offers and career changes. Some prospective employees are dissuaded because fields such as epidemiology require many years of study and training, the report said.

Those trends are occurring during some of the deepest state budget cuts in 60 years. Paradoxically, the decrease in employees comes at a time when public health is widely acknowledged to have a key role in addressing the threats of terrorism and emerging infectious diseases.

"The events of September 11, 2001, and the anthrax attacks brought the role and responsibility of the public health workforce in emergency response efforts to the forefront in public understanding," said ASTHO President-Elect Richard A. Raymond, MD, in an ASTHO press release. "We can only be prepared if we have an experienced workforce that is qualified to carry out our mission."

More than 50% of the responding states reported they lacked qualified public health employees or employees who were willing to relocate to fill preparedness gaps. In addition, several state public health agencies reported they could lose over 40% of their workforce through retirement by 2006.

A lack of public health laboratory personnel highlights the challenge of emergency preparedness. For example, 13 states responding to the survey had no doctoral-level molecular scientist; 23 states had one. Most officials questioned said that ensuring emergency preparedness demands two doctoral-level molecular scientists on staff.

The role of these scientists is crucial, Steib explained. They are the front-line people who can tell one anthrax strain from another or determine whether foodborne illnesses in different states are linked.

Federal funds are available to help pay workers, but departments still can't find employees, she added.

To counter the decline in workforce numbers, states are considering or trying a broad range of incentives, including offering higher pay, allowing flexible scheduling and telecommuting, providing professional training, conducting outreach campaigns to educate students about the field, and connecting employees to leadership institutes. Some states are rehiring retired employees to prevent further erosion of institutional knowledge.

Experts are also considering using loan-forgiveness legislation, grants, and scholarships modeled on programs that allow doctors to get financial assistance in exchange for working in a specific area. Offering financial incentives might offset some of the losses detailed in the report, Steib said.

Amy Becker is a full-time reporter at the St. Paul Pioneer Press and a freelance reporter for CIDRAP. She will enter the University of Minnesota's graduate program in public health administration and policy in fall 2004.