Mar 16, 2011 (CIDRAP News) – Chinese researchers who have been investigating puzzling outbreaks of a febrile illness in rural areas that they thought might be anaplasmosis reported today that they identified a new bunyavirus, one that may be transmitted by ticks.

The discovery came from an investigation by China's Center for Disease Control and Prevention into outbreaks of an illness that they termed severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS). The outbreaks were reported in central China's Hubei and Henan provinces in the spring and summer of 2009.

The group reported its findings today in an early online edition of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

Patients had fever and gastrointestinal symptoms, along with thrombocytopenia and leukocytopenia. Initially the case-fatality rate was 30%. And though the symptoms resembled anaplasmosis, DNA and antibody tests turned up no evidence of the disease in patients' blood samples. Researchers did find a novel virus from one patient's blood, a 42-year-old male farmer from Henan province.

Their investigation into infections that fit the same profile in hospitalized patients in other provinces in central and northern China helped them characterize the new virus.

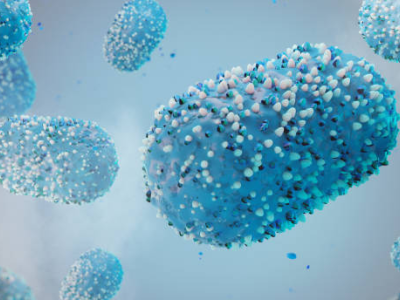

Bunyaviruses are one of four viruses that fall under the hemorrhagic fever virus umbrella. The new virus, which the researchers termed SFTS bunyavirus (SFTSV), is a phlebovirus member of the bunyavirus family, which is divided into 68 antigenically distinct serotypes, 8 of which—including Rift Valley fever—have been linked to disease in humans.

Active surveillance in six provinces identified patients who met the SFTS case definition, and the presence of the new virus was confirmed in 171 of them. The investigators collected serum samples within 2 weeks of illness onset and again during the convalescent phase. For comparison they also collected serum samples from 200 matched healthy people who lived in the same area at the same time.

Phylogenetic analysis of virus isolated from the farmer's blood, plus 11 from patients with the same illness in other provinces, showed that the new virus belonged to the phlebovirus genus, but was more distantly related to the other four bunyavirus types. Further analysis suggested the SFTSV isolates clustered together phylogenetically but were located the same distance away from the other two groups, the Sandfly fever group and the Uukuniemi group. A comparison of amino acid sequences also found that SFTSV was distinct from other phleboviruses.

A serological study of 35 patients who had samples taken during both acute and convalescent phases found high levels of neutralizing antibodies during the convalescent phase, with some persisting even 1 year after recovery.

During the clinical and epidemiological studies, they found that symptoms were nonspecific, with the major ones being fever and gastrointestinal problems. Lymphadenopathy and multiorgan failure were also features of the disease.

Of 171 confirmed cases, they found 21 deaths, for a case-fatality rate of 12%, though the researchers said it's not clear how SFTSV caused the deaths. About three quarters of the patients were older than 50, roughly half were women, and most were farmers who lived in wooded and hilly areas and worked in fields before they got sick.

Though mosquitoes and ticks were common around the patients' homes, viral RNA was not found in any mosquitoes but was detected in 5.4% of ticks (Haemaphysalis longicornis) that were collected from domestic animals in the areas where patients lived. The group found no evidence of human-to-human transmission of the disease.

The researchers cautioned that their findings don't fulfill Koch's postulates for linking a microbe to a disease, though they do suggest that SFTS is caused by a newly identified bunyavirus. "It is most likely that SFTS has been prevalent in China for some time, but it has not been identified," they wrote.

The clinical profile of the new bunyavirus infection will help medical teams distinguish it from illnesses with similar presentations such as anaplasmosis, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, and leptospirosis.

They concluded that the identification of the new bunyavirus is a benefit of heightened surveillance for infectious diseases in China.

Heinz Feldmann, MD, PhD, a viral hemorrhagic fever expert at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), wrote an editorial on the study that appears in the same NEJM issue. He said the Chinese study was well done and included several key components, such as a discussion of the disease syndrome, expanded surveillance, identification of the vectorborne virus, and screening of ticks and mosquitoes. Feldmann is also with the department of medical microbiology at the University of Manitoba.

He said it's likely that China has already been experiencing cases of the disease, but the study illustrates how important clinical surveillance is on the frontlines of disease identification and defense. In the editorial, he wrote that the identification of the new virus, like the emergence of the 2009 H1N1 virus, remind the global health community to expect the unexpected.

Feldmann told CIDRAP News that the connection between the disease and the new virus is pretty strong. "They fulfill most of the Koch postulates," he said.

The next step is to develop an animal model to mimic disease symptoms, which could be difficult, Feldmann said. "Not everyone is equipped to do that kind of work."

Data on the tick vector for the new virus looks good but is preliminary and will require more studies, he said. Researchers will need to determine which animals the ticks feed on and what impact the animals have on human health, Feldmann said. For example, the Rift Valley fever virus, another member of the bunyavirus family, infects humans during the slaughter of viremic livestock.

Yu XJ, Liang MF, Zhang SY, et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med 2011 Mar 16;10(1056) [Abstract]

Feldmann H. Truly emerging: a new disease caused by a novel virus. (Editorial) N Engl J Med 2011 Mar 16;10(1056) [Abstract]