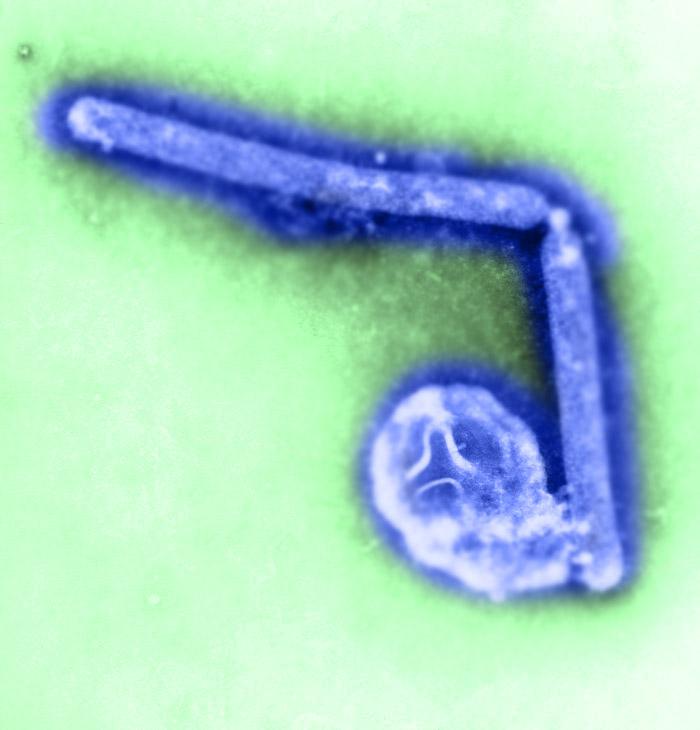

A report published by Alberta health officials over the weekend lays out the swift clinical course of the H5N1 influenza infection that killed a young Alberta woman on Jan 3, including brain inflammation and swelling, an unusual complication in human H5N1 cases.

The woman, a nurse in Red Deer, Alta., fell ill while returning from a 3-week trip to Beijing on Dec 27. How she was exposed to the virus remains unknown, since she had no contact with poultry during her trip, and no H5N1 outbreaks have been reported in Beijing recently.

The case is the first human H5N1 illness reported in the Americas. Of 649 cases reported since 2003, 385 have been fatal, according to the World Health Organization.

The case report was posted on ProMED-mail, the reporting service of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, on Jan 12. Kevin Fonseca, PhD, a clinical virologist with Alberta Health Services, served as lead author and was joined by a number of colleagues from the provincial agency.

The patient experienced malaise, chest pain, and fever during her Dec 27 homeward flights, prompting her to go to a hospital emergency department the next day, according to the report. After a chest x-ray and computed tomographic scan suggested pneumonia, she was prescribed an antibiotic and sent home.

She returned the next day, Dec 29, with worsening chest pain, shortness of breath, a mild headache, nausea, vomiting, and other symptoms. Another x-ray indicated worsening pneumonia, and the patient was admitted to the hospital and treated with additional antibiotics.

On Jan 2 the woman reported visual changes along with a persistent headache. In view of this and her increasing need for oxygen, she was admitted to the intensive care unit for intubation and mechanical ventilation, the report says. Early the next morning she had sudden tachycardia and severe hypertension, followed by hypotension, necessitating steps to keep her heart beating.

At this point the patient's pupils were dilated and she did not respond to pain, the report says. A CT brain scan then suggested diffuse encephalitis and intracranial hypertension, and a neurologic exam indicated brain death. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed swelling, signs of meningitis, and a reduction in cerebral blood flow.

Avian flu was deemed unlikely but possible

The report says the attending physician thought avian flu was unlikely but possible in view of the patient's travel history and neurologic condition. That prompted notification of local public health officials on Jan 3, followed by tracing of the woman's family and hospital contacts.

After tests for various bacterial pathogens were negative, respiratory samples were sent to the provincial laboratory to test for flu and other viruses. The samples tested positive for influenza A, but specific tests for H3N2 and 2009 H1N1 were negative, which, in combination with the travel history, pointed to a strong possibility of an avian flu virus.

A combination of further tests then indicated the virus was H5N1, and subsequent tests at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg confirmed this conclusion. The virus was found in the patient's cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as well as respiratory samples. Testing also detected a common human coronavirus (229E) in nasopharyngeal samples, as reported previously.

"From a laboratory diagnosis standpoint, this case shows the value of having screening assays, in-house or commercial, known to be capable of identifying all influenza subtypes," the report says. It adds that conflicting results between in-house screening assays and a commercial respiratory test panel were helpful in indicating that the virus was not a seasonal subtype.

The authors also sequenced the virus's hemagglutinin and neuraminidase genes, which revealed that it belongs to H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1 and is sensitive to oseltamivir (Tamiflu). The latter information was helpful because preventive oseltamivir treatment had been prescribed for the patient's close contacts.

The report also says that no autopsy was done because of concern about the risk of virus transmission.

Brain complications in previous H5N1 cases

The authors say brain infections are uncommon in H5N1 cases, although animal studies show that the virus can invade the central nervous system (CNS). They reference a review of human H5N1 cases published in The Lancet in 2008, which cited one patient who had a coma along with evidence of the virus in CSF, suggesting CNS involvement. That review also said a few autopsies of H5N1 victims suggested that the virus replicated in nonrespiratory tissues, including the brain.

Tim Uyeki, MD, MPH, an influenza expert with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said neurologic manifestations are seen occasionally in seasonal flu cases and have been reported in a few H5N1 cases.

"There are cases every winter of seasonal influenza–associated encephalopathy or encephalitis, typically in young children," he said in an interview. He noted that influenza virus infection of the respiratory tract can cause cytokine dysregulation, the intense inflammatory response also known as cytokine storm, and this is believed to be the cause of neurologic complications in seasonal flu cases.

"Seasonal influenza viruses are not thought to be infecting the brain," Uyeki said. "But inflammation can produce a fulminant encephalitis."

In the rare H5N1 cases with neurologic complications, however, the picture seems a little different, in that there has been some evidence of actual infection in the brain, he said.

For example, a 2007 report in The Lancet reported on two H5N1 cases, one of which involved a man who had pneumonia and, while hospitalized, experienced irritability and convulsions followed by decreased consciousness. An autopsy revealed evidence of H5N1 virus infection in his brain, Uyeki said, adding, "So that suggests that H5N1 virus can directly infect brain tissue. H5N1 virus can disseminate from the lungs into the blood, and then spread throughout the body, including to the CNS."

He also noted that a report in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2005 said that H5N1 virus was isolated from the CSF of a child with encephalitis who died.

Commenting on the Canadian case, Uyeki said, "It is possible that H5N1 virus may have spread from the lungs to the blood and then to the CNS. This patient's encephalitis could be secondary to infection of the brain, because H5N1 viral RNA was detected in the cerebrospinal fluid [by PCR]. That suggests there was virus infection of the CSF, but unless you isolate the virus, it doesn't prove it was present."

He added that the patient's encephalitis also could have been caused by inflammation triggered by the infection in the respiratory tract (pneumonia).

Uyeki also commented that a few other H5N1 cases with CNS complications have occurred worldwide but have not been reported publicly. "It's not unprecedented, but it's probably rare," he said.

See also:

Jan 12 ProMED post

PubMed abstract of 2008 Lancet H5N1 review