A federal policy unveiled yesterday lays out the responsibilities of institutions in identifying and regulating "dual use research of concern" (DURC), which include calling on scientists to flag their own experiments that potentially fall in that category.

The aim is to identify experiments that meet the DURC definition—ones that generate knowledge or products that could be used to cause significant harm as well as good—so that plans to prevent or minimize the risks can be developed.

The policy, which will take effect on Sep 24, 2015, applies only to institutions that receive federal research funding. It is intended to complement a policy announced in 2012 that spelled out the role of government funding agencies in identifying and regulating DURC in the life sciences, federal officials said at a press conference.

'Culture of responsibility' sought

Officials made clear that the government is still the final arbiter of what counts as DURC and what risk-mitigation steps are needed, but they said the new policy marks an effort to develop a "culture of responsibility" among researchers and institutions regarding risks associated with life sciences research.

"What we tried to build was sort of a grass roots approach where those most connected to the research were the ones flagging it," said Andrew Hebbeler, PhD, assistant director for biological and chemical threats in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

"The onus is not on the principal investigator [PI] to identify the security considerations and DURC itself, but it's asking the PIs to be aware of the pathogens involved," he said. If a project involves one of 15 specific pathogens or toxins covered by the policy and any of seven different categories of experiments, the PI should alert the relevant institutional review entity (IRE) so that it can evaluate the project, according to the policy.

"This is clearly a learning curve and in many ways a culture shift for the life sciences community at the grass roots level to think about public health and security considerations," said Amy Patterson, MD, associate director for biosecurity and biosafety policy at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

"We'll be doing case studies and workshops at institutions across the country," she added.

"Importantly, at the end of the day the decision on whether projects go forward or not and whether a risk mitigation plan is appropriate or not is made by the funding agency," Patterson said.

In response to a question about why institutions need to duplicate review processes that are already being done by federal agencies, she said, "It's a complementary process. . . . It's important for institutions and investigators to gain experience in thinking through dual-use issues. They need to be mindful of whether dual-use issues emerge during the research process. We hope that institutions and investigators will be well poised to identify DURC as a result of this process."

Hebbeler added, "The policies . . . are really trying to build that culture of responsibility in the life sciences. This can't just be a federal government–driven effort."

Steps for compliance

The new policy lists a series of steps that an institution is supposed to take once a researcher has alerted the panel that a project may qualify as DURC.

First the IRE is supposed to determine if the federal agency has already identified the project as DURC. If not, the IRE checks the PI's conclusion that the project involves one of the 15 defined pathogens and one of the seven kinds of experiments governed by the policy.

If it does, the IRE is to conduct a risk assessment to determine if the project meets the DURC definition. If the answer is yes, the panel is expected to weigh the risks and anticipated benefits and, working with the government funding agency, write a draft risk mitigation plan within 90 days.

The funding agency then is supposed to finalize the risk mitigation within 60 days of receiving the institution's draft. Finally, the institution is required to implement the plan and provide ongoing oversight of the research.

Patterson noted that the government has developed an online "companion guide" to help institutions with day-to-day decisions about DURC, and she said other teaching tools are being developed as well.

List of pathogens not set in stone

At this point the DURC policy applies to 15 specific pathogens and toxins, but the list will continue to be evaluated in coming months and years, said Hebbeler and Patterson. The agents and pathogens are:

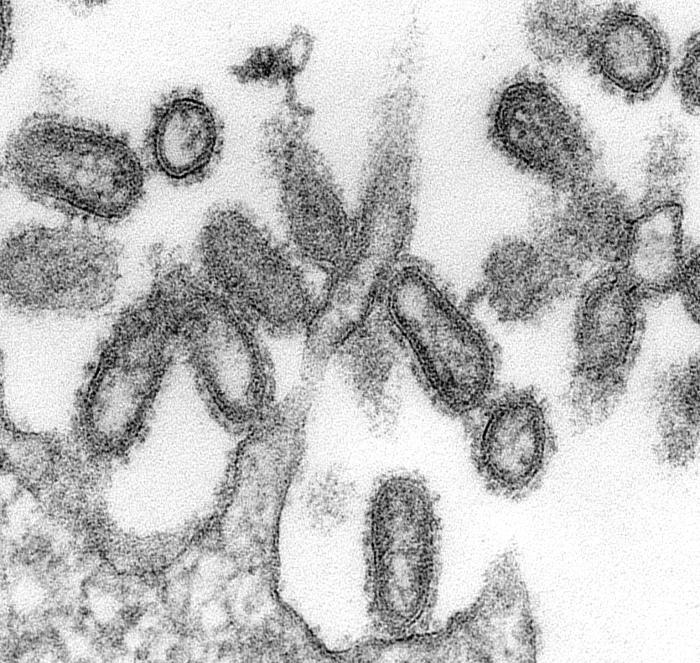

- Highly pathogen avian influenza viruses

- Bacillus anthracis (the cause of anthrax)

- Botulinum neurotoxin

- Clostridium botulinum (botulism)

- Burkholderia mallei (glanders)

- Burkholderia pseudomallei (melioidosis)

- Ebola virus

- Foot-and-mouth disease virus

- Francisella tularensis (tularemia)

- Marburg virus

- Reconstructed 1918 flu virus

- Rinderpest virus (the cause of a recently eradicated cattle disease)

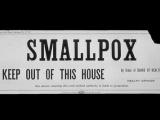

- Variola major virus (smallpox)

- Variola minor virus (a milder strain of smallpox)

- Yersinia pestis (plague)

The DURC definition further specifies seven types of experiments: those that aim to or are expected to:

- Enhance the harmful effects of the agent or toxin

- Disrupt immunity or the effects of immunization without clinical or agriculture justification

- Render the agent resistant to preventive or treatment drugs or increase the agent's ability to evade detection

- Increase the stability or transmissibility of an agent or the ability to disseminate it

- Change an agent's host range or tropism

- Enhance host susceptibility to an agent

- Generates an extinct agent among the 15, such as variola or rinderpest virus

Patterson said the DURC policy applies to projects already under way as well as new ones. She said there are "a couple hundred" current government-funded projects that investigate various aspects of the 15 listed agents and toxins, but only a handful of those were identified as DURC under the 2012 policy.

"When they were identified, the federal government followed up with the institutions to review those projects and amend those," she added.

In response to a question, Patterson said the policy does not apply to seasonal flu viruses, but if researchers proposed to change a virus in ways that made it more dangerous, they would have to submit the project for a review regarding the proper lab biocontainment level.

Penalty is funding cutoff

The penalty for violating the institutional DURC policy is withdrawal of federal funding, Patterson said. Depending on the circumstances, the scope of the cutoff could range from one particular investigator to the whole institution.

"That's at the end of the day a fairly large stick, if you will, and one most institutions try very hard to avoid," she said.

The policy document says institutions that do non–government-funded research on any of the 15 listed agents are still subject to the policy if they get government funds for other life sciences research.

Gain-of-function deliberations

The press conference occasioned questions about US policy on "gain-of-function" (GOF) research, which generally refers to experiments that involve increasing the virulence, transmissibility, or host range of pathogens, in the name improving surveillance and control measures. The concern about GOF studies has focused chiefly on accidental release of dangerous pathogens, rather than deliberate misuse.

Hebbeler said GOF research policy is under active discussion, but he couldn't give any details, except to say that the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) will be asked to think about the risks and benefits of GOF studies when it meets in October.

"Stay tuned in terms of policy development in this area," said Patterson.

Mixed views from experts outside government

Two infectious disease experts outside the government expressed a mix of views about the policy on institutional oversight of DURC.

David A. Relman, MD, a professor of medicine and of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University, told CIDRAP News, "I would view this as still very much a 'work in progress.' Local institutions and PIs will need further guidance about how exactly to make these determinations, and then how to address research of concern. Beyond that issue, I think most agree that this 'list' [of agents] is extremely limited and overly narrow in its construct. There is plenty more work that deserves similar kinds of attention."

Relman, who is also chief of infectious diseases at Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System and a former NSABB member, added that the life sciences community is still in the very early stages of thinking about research-related risks.

"Too many, so far, have wanted to simplify the issue and in essence, sweep it to the side. I am encouraged that [the US government] wants to keep the issues alive and draw attention," he said. "But how the institutions within the life sciences enterprise should then respond is unclear and under-prioritized."

Andrew Pekosz, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University's Bloomberg School of Public Health, said in an interview that the policy seems fairly clear and straightforward, but he expressed some concern about the time that DURC deliberations will require and the burden on university committees.

The policy "seems fairly straightforward and organized, so for the most part it should be easy to interpret. So I'm happy with it as it is," said Pekosz, who is an associate professor in the W. Harry Feinstone Department of Molecular Microbiology & Immunology and the Department of Environmental Health Sciences. "There has to be some level of oversight here, and at least this spells things out."

But he said that the timeline for DURC considerations suggests it could cause significant delays, which can put more pressure on researchers as the timelines for grant applications get shorter. Noting that the policy allots 90 days for completion of a risk mitigation plan after a project is determined to be DURC, he said, "That's a nightmare time to wait. I'd much prefer to see that as a much shorter timeline."

Pekosz said that at most institutions, the existing institutional biosafety committee will probably assume the role of the IRE for DURC. The deliberations on DURC will probably be more open-ended than what institutional review boards typically engage in, he predicted.

"That committee is going to have to come up with safety factors that are not regulated by government rules at this time," he added. "The expertise of university committees is going to be tested, and it's going to be a burden on them to come up with these things."

He also said there is a fear among researchers that "irrespective of the experiment being proposed, the easy response is, 'no we shouldn't do those things because we can't come up with a good safety mitigation factor.'"

See also:

US policy for institutional oversight of life sciences DURC (19 pages)

March 2012 DURC policy for federal agencies

Companion Guide to the policies on DURC oversight (77 pages)

Sep 24 White House Office of Science and Technology blog post

HHS DURC page with links to policies and other resources