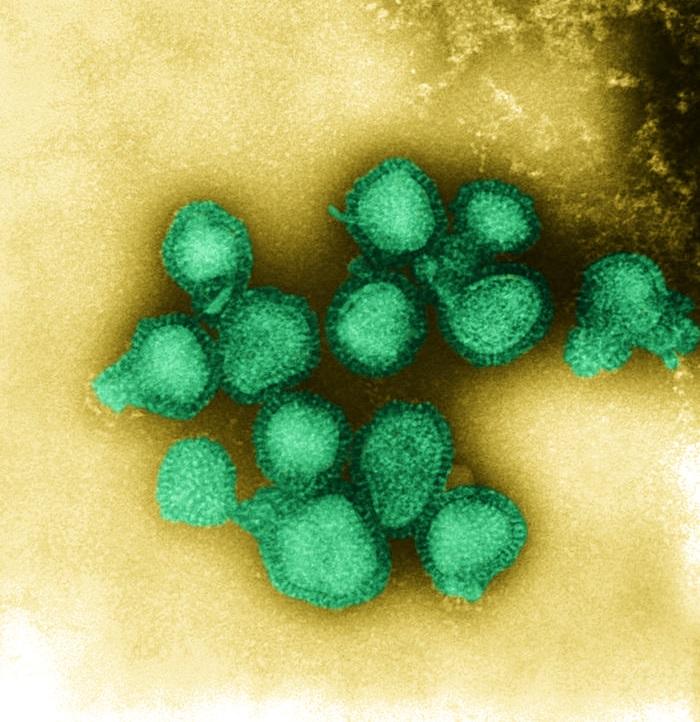

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned yesterday that the profile of influenza viruses currently circulating, with A/H3N2 predominant, suggests a risk for a rough ride this winter, especially since about half of the H3N2 viruses don't match up with the corresponding strain in this year's vaccine.

CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, observed that seasons dominated by H3N2 viruses are generally worse than other seasons, and warned that the mismatch between the vaccine and circulating strains may portend lower vaccine effectiveness (VE) than usual. Consequently, he emphasized that antiviral medications are an important second line of defense, especially for patients at risk for flu complications.

At a press conference, Frieden said the vaccine may still yield some protection against H3N2, despite the mismatch. At the same time, he cautioned that it's still early in the season and flu is highly unpredictable, so anything could happen.

In response to the CDC advisory, some flu experts raised questions about the wisdom of focusing public attention on findings of a vaccine mismatch with circulating flu strains. They say there seems to be little correlation between vaccine match and how well the vaccine works, and that even with an apparent mismatch, the vaccine should still provide some protection from infection. The critical point, they suggested, is that H3N2-dominated flu seasons tend to be more severe.

The CDC advice comes in the wake of a number of recent findings that have raised questions about the effectiveness of flu vaccines under various conditions. In November, for example, the CDC reported that the intranasal vaccine FluMist (live attenuated influenza vaccine, or LAIV) did not seem to be effective against H1N1 viruses in young children in the 2013-14 season. Other recent studies have suggested that getting a flu shot 2 years in a row may reduce the vaccine's effectiveness the second year.

On the other hand, some studies have indicated that the benefits of flu vaccination may last more than one season.

H3N2 viruses hold super-majority

At the press conference, Frieden said that about 90% of about 1,200 respiratory samples tested through the week before Thanksgiving week were type A viruses, and about 9% were type B.

Of the type A viruses, nearly all were H3N2, and about half of those were antigenically different from the H3N2 component of the vaccine, he explained. Today's FluView report from the CDC—which covers Thanksgiving week—placed the mismatch rate at 58%, up from 52% the week before (see related Flu Scan).

He said the "drifted" (slightly mutated) H3N2 viruses were first noticed in March, too late to include in this year's vaccine. "The H3 component of the vaccine was still by far the most common of the H3N2 viruses" at the time, he said, adding later that it wasn't until September that the new strain became common.

"Both strains are likely to continue to circulate in the US this season, and there's no way to predict what's likely to happen," Frieden said. "Only time will tell which of them, if any, will predominate for the following weeks and months of this season." He added that rates of hospitalization and death tend to be twice as high or more during H3N2-predominant seasons.

In a press release yesterday, the CDC said, "H3N2 viruses were predominant during the 2012-2013, 2007-2008, and 2003-2004 seasons, the three seasons with the highest mortality levels in the past decade. All were characterized as 'moderately severe.' "

Frieden said the circulating type B strains are well matched to the vaccine so far this season. "We continue to recommend flu vaccine as the best way to protect yourself against influenza," he added.

"The vaccine may have some effectiveness against the drifted [H3N2] strain," he said, adding later, "During some seasons when viruses are antigenically drifted, vaccine effectiveness can be lower, but not always."

In a Health Alert Network (HAN) notice this week, the CDC said that a poor vaccine match with circulating viruses has been associated with lower VE in past seasons, but it still provided some protection against drifted strains.

"Though reduced, this cross-protection might reduce the likelihood of severe outcomes such as hospitalization and death," the statement said. "In addition, vaccination will offer protection against circulating influenza strains that have not undergone significant antigenic drift from the vaccine viruses (such as influenza A (H1N1) and B viruses)."

Frieden noted that five children have died of flu-related causes this season. Joseph Bresee, MD, chief of the CDC's Influenza Epidemiology and Prevention Branch, said three of the children had H3N2 infections, but it is not known whether any of them involved the drifted strain.

The CDC officials also were asked about their report in November that LAIV did not seem to protect young children against H1N1 viruses in the 2013-14 season.

Frieden and Bresee said the CDC continues to recommend the use of FluMist in young children, or an injectable vaccine if it's not available. H1N1 viruses are uncommon so far this season, they added, and FluMist is likely to be effective against "matched strains." Also, they said they are continuing to investigate the earlier finding and what might explain it.

Emphasizing antivirals

The potential for a tough flu season magnifies the importance of using the antiviral drugs oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza), particularly in patients who have chronic diseases that increase their risk for flu complications, Frieden said.

He said the drugs, when started early in the illness, can reduce the duration of symptoms and the risk of dying. "Antiviral drugs are very underprescribed," he added. "Probably fewer than one in six who are severely ill with flu get antiviral drugs. We need to get the message out that treating early with these drugs can make a difference between having a mild illness or a severe illness."

He said physicians should not wait for flu test results before prescribing an antiviral if otherwise indicated, and that patients who have flu symptoms and an underlying illness should seek treatment immediately.

Bresee said the CDC is not aware of any current antiviral shortages and expects the supply to meet the demand this season.

Similarly, Frieden said he's not aware of any flu vaccine shortages, other than a few spot shortages. He said 145 million doses of vaccine have been distributed, and that should be sufficient for the demand.

Questions on vaccine match and effectiveness

The CDC officials were asked about the correlation between vaccine match and VE and whether a better measure of VE is needed.

"It's clear that the laboratory tests we're using to understand how closely related this virus is to the vaccine virus are good, but they're imperfect markers of how well the vaccine will function in the field," Bresee replied, adding that the CDC conducts observational studies of VE each season.

"We'll have that data sometime in the middle of the season," he said. "You're right to the extent that these [tests of vaccine match] aren't perfect markers of what to expect in terms of how well the vaccine will work, but they are related to how well the vaccine works."

The relationship of vaccine match, as currently assessed, to VE has been questioned increasingly in recent years. The match is assessed using ferrets that have never been exposed to flu before. The animals are infected with one of the viruses targeted by the vaccine, and serum samples are subsequently collected. A hemagglutination inhibition (HI) test is then used to measure how well antibodies in the serum recognize and bind to other flu viruses, such as one isolated from a patient.

A drawback of this method, however, is that the ferrets are naive to flu, whereas humans other than young children have been exposed to many flu viruses and flu vaccines over the years. As a result, humans typically carry a whole library of flu antibodies, which makes their response to a virus much more complex than that of a ferret in a lab.

This fact was illustrated by a recent study described in Science, in which researchers conducted more than 10,000 HI tests to construct H3N2 "antibody landscapes" or profiles for 69 people over a wide range of ages. They found that titers were highest for antibodies that had circulated when individuals were about 6 years old and tended to be lower for newly circulating viruses than for earlier strains. Also, they found that infection with an H3N2 virus resulted in a "notably broad antibody response that was typically governed by the extent of the preexposure antibody landscape."

An outdated assessment?

Michael T. Osterholm, PhD, MPH, said he and his colleagues couldn't find a good correlation between vaccine match and VE when they conducted a rigorous meta-analysis of flu VE studies a few years ago. Osterholm is director of the University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP), publisher of CIDRAP News.

"It's become clear over the past several years that the current method for matching vaccine strains to circulating strains is almost an outdated assessment of the ability of a vaccine to protect against a strain of influenza," he said.

"The methods are such a crude indicator that they don't correlate highly with protection," he said. "For all we know, this [year's] vaccine could work as we'd expect to see it work in other years. Just because it's a bad match by this method doesn't mean it won't work. But if it's a good match, it doesn't necessarily mean it will be protective."

Osterholm also took issue with the CDC's suggestion that a mismatched flu vaccine, even if it doesn't prevent flu, may reduce the risk of severe outcomes like hospitalization. "There is no convincing evidence that, if you get vaccinated with a vaccine that is not well matched to the circulating strain using our current test methods, there is any reduction in disease severity or mortality," he said, adding that the same caveat applies even if the vaccine seems well-matched to circulating viruses.

"That's an unfortunate statement that is part of what has historically been an overstatement of the public health impact of flu vaccine."

However, he added that he still recommends vaccination as the best available tool for preventing flu. He also agreed about the importance of the message that H3N2-dominated flu seasons are generally worse than those dominated by other flu varieties.

H3N2 dominance seen as main concern

Edward Belongia, MD, director of the Epidemiology Research Center at the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation in Wisconsin, agreed that the association between vaccine match and effectiveness is fuzzy and said that the primary concern now is the likelihood of an H3N2-dominated flu season. Belongia participates in the CDC's US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

"The relationship between vaccine match as currently defined and actual clinical vaccine effectiveness is not very clear," he said. "One of the unfortunate aspects of the interpretation of this CDC advisory is that some media are interpreting it as saying the vaccine won't work this year.

"The CDC advisory sort of raises a lot of questions and doesn't provide a lot of clarity. The most important thing to keep in mind, really more important than the antigen match question, is that this is going to be an H3N2 season. We know we have more hospitalizations and more deaths in an H3N2 season. The other thing is that in general the vaccine effectiveness is not as high in an H3N2 season as in other seasons."

Belongia said the vaccine should provide some protection against H3N2 viruses even if there's a mismatch. Speaking of flu vaccines in general, he said, "We tend to see protection in the 40% to 60% range, regardless of match or mismatch. Sometimes it's a little less than that for H3N2."

He added, "The relationship between the antigenic match or mismatch and actual protection is not straightforward, and it's not correct . . . to conclude that the vaccine is not effective or less effective."

When there's a "huge" mismatch between the vaccine and a circulating strain, such as when the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus emerged, "there's no question that you're not going to be protected," Belongia said. "But when you have this mild antigenic drift, what that means for vaccine effectiveness is not clear and may not be the same for different age-groups."

He agreed with Osterholm on the question of whether a vaccine can limit the severity of illness even if it fails to prevent flu in the first place: "I don’t think there's any convincing evidence that the vaccine, if not preventing flu, is still giving you a milder illness."

He and his colleagues did a multi-season study of whether outpatients who got sick with flu were less likely to be hospitalized if they had been vaccinated. "The answer was no. Once you got flu, whether you were vaccinated or not, it had no effect on the likelihood of being hospitalized."

He added that some studies have hinted that vaccination may be linked to a reduction in severity of illness, but the findings were not conclusive.

Belongia also commented that he agreed with the CDC's advice about the importance of antiviral treatment for high-risk patients. "That advice applies in any season, and especially in an H3N2 season. I don't think whether some of the viruses are drifted is really the main message here."

See also:

Dec 4 CDC press release

Dec 3 CDC HAN notice

Transcript of Dec 4 CDC press briefing

Nov 7 CIDRAP News story about LAIV effectiveness against H1N1 in kids

Nov 26 CIDRAP News story on effects of consecutive-year flu shots

CDC information on how antigenic match is assessed

Nov 21 Science abstract on human flu antibody landscapes