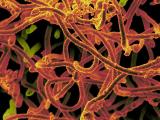

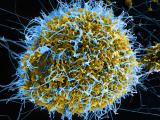

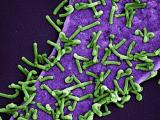

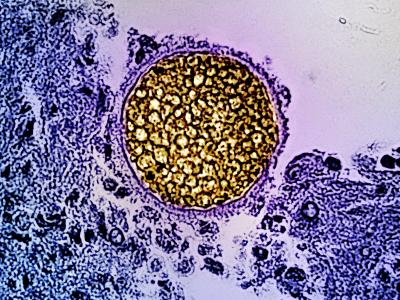

French and Guinean researchers today noted how chains of transmission helped Ebola spread in Conakry, Guinea, the first of the region's capital cities to be hit by the virus, and US officials released three detailed reports on outbreak response.

The Conakry team looked at seven transmission chains that occurred in the area from March to August 2014. They reported their findings in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Ebola infections have been occurring in Conakry for 10 months, with the virus first arriving from Donka, sparking the first wave of infections.

Urban challenges

The team's analysis of transmission chains found that officials thought they had the first illnesses contained, but an uncooperative family was linked to latent infections that likely sparked a second wave. A third wave of illnesses was sparked by virus reintroduction from Sierra Leone.

Transmission chains in Conakry spread to two other areas of Guinea, highlighting the challenge of battling the disease for large urban centers when populations are highly mobile, the authors noted.

The group's analysis also found that hospital transmission was high in March, but quickly fell, with health workers playing little role in the spread of the virus. However, they said a second "super-spreading" event was connected to a hospital in July and caused by loosening of earlier controls.

Funeral-linked spread of the disease decreased as controls were put in place, and most Ebola transmission took place in the community and among families.

They said a more detailed spatial analysis factoring in mobility and demographic data are needed to make stronger conclusions about the role urban areas play in the spread of Ebola.

Writing in a commentary on the study, Christian Drosten, MD, a virologist at the University of Bonn, said transmission reductions due to controls at funerals is an encouraging message from the first African capital affected by the disease. He added, though, that the level of disease in the community was enough to keep the outbreak in the city going.

Further, he said hospital admission was the only measure that appeared to slow the spread of the disease in the community.

Two independent introductions into Conakry during the study period suggest that the city was the recipient rather than the amplifier of outbreaks, Drosten wrote, adding that a surge of infections in November underscores that point.

Contact tracing after Texas case

In the first of three reports today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), extra flight contact tracing measures undertaken after a Texas nurse took two flights shortly before getting sick with Ebola in October identified 268 people from nine states, none of whom got sick with the virus.

Health officials from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and their state partners who helped with the investigation noted that nurse Amber Vinson flew from Dallas to Cleveland on Oct 10, returning to Dallas on Oct 13, the day before she reported symptoms.

The CDC said it went beyond its normal protocols to protect public health and address the public's concerns. The investigation found that Vinson didn't experience vomiting or diarrhea during the flights.

Of the contacts, 28 passengers, 3 flight crew members, and 1 member of the cleaning crew reported possible Ebola symptoms during the 21-day monitoring period. Only one person—a contact who had fever and respiratory symptoms—was tested for Ebola, and tests on days 1 and 3 of symptoms were negative.

After it was clear that disease dynamics hadn't changes, the CDC eased its guidance on passengers that were deemed to be in the higher-risk groups. The authors concluded that their findings suggest airline transmission is low when possibly contaminated body fluids aren't involved.

Impact of treatment units

In the second report, CDC estimates on the impact of Ebola treatment units (ETUs) and community care centers (CCCs) in Liberia predict that the interventions prevented thousands of new infections and that the interventions when used together were likely had a bigger impact than either alone.

Researchers used an Ebola modeling tool based on data from earlier outbreaks. Their analysis revealed that from Sep 23 to Oct 31, placing 20% of patients in ETUs would prevent 2,244 cases and that placing 35% of patients in CCCs and encouraging safe burials might prevent 4,487 cases. Both interventions used together during the same period would have prevented an estimated 9,097 cases, according to the study.

The experts wrote that in large Ebola outbreaks, rapidly deploying both ETUs and CCCs can reduce the number of Ebola infections.

Boosting surveillance

In the third report, CDC and other scientists noted that Sierra Leone's Ebola case surge in the summer and fall overwhelmed surveillance systems, with many cases not found until victims were dead, posing a high risk to communities.

To help identify cases earlier and curb the spread of the disease, the International Rescue Committee, the CDC, and officials in the country's Bo district developed a community event-based surveillance (CEBS) system to boost the response and regular surveillance.

The CEBS system involved training local people to recognize key events, such as two of more ill or dead family members, a dead health worker, or a death in someone who attended a funeral.

A pilot project of the system in Bo district showed high acceptance among community members and responders, and plans are under way to expand the CEBS system to other parts of Bo district and in different parts the country, according to the report.

See also:

Jan 23 Lancet Infect Dis study

Jan 23 Lancet Infect Dis commentary

Jan 23 MMWR report on flight contact tracing

Jan 23 MMWR report on ETU and CCC impact

Jan 23 MMWR report on CEBS system