The World Health Organization (WHO) today unveiled its first global foodborne disease estimates, which show that tainted food sickens 1 in 10 people each year, with the youngest children at greatest risk and threats varying by region.

The findings are the result of a massive effort to collect data that took nearly a decade. Today's 256-page report distills scientific papers that were published today in a Public Library of Science (PLoS) special collection.

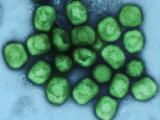

An initiative to gauge the burden launched in September 2006, which led to the establishment of a Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG). Dividing the tasks into six taskforces, the group commissioned studies that looked at 31 hazards, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, toxins, and chemicals.

Margaret Chan, MD, MPH, the WHO's director-general, said in a press release that until now, foodborne disease estimates have been vague and imprecise, concealing the true human cost. "Knowing which foodborne pathogens are causing the biggest problems in which parts of the world can generate targeted action by the public, governments, and the food industry," she said.

Burden heavy on kids

According to the estimates, foodborne illnesses sicken about 600 million people each year worldwide, leading to 420,000 deaths. Nearly a third of the deaths are in children younger than age 5, though they represent only 9% of the general population.

Diarrheal illnesses cause 550 million of the cases and almost half of the deaths, according to the report. Again, children make up a large portion of patients who contract diarrheal disease, commonly caused by norovirus, Campylobacter, nontyphoidal Salmonella, and pathogenic Escherichia coli.

Some of the other major contributors to the overall global total include typhoid fever, hepatitis A, Taenia solium (a tapeworm), and aflatoxin (a type of mold on improperly stored grain).

Foodborne disease risks are highest in low- and middle-income countries for a host of reasons, including unsafe water for preparing food, poor conditions for food production and storage, and lack of food safety controls.

Salmonella is one disease that poses a big threat across both high- and low-income countries, while others are more common in developing countries: typhoid fever, foodborne cholera, and E coli. Researchers found that Campylobacter, in contrast, is an important pathogen in high-income countries.

Alongside acute symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea, some of the disease linked to contaminated food can cause serious lingering problems, such as cancer, kidney or liver failure, or neurologic disorders.

Besides totaling the deaths, the experts calculated the disease burden by the number of healthy years lost due to illnesses and death as a means of comparing diseases across regions. The global burden for 2010 was 33 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), with kids under 5 bearing 40% of the burden.

The WHO said the report findings underscore the need for governments, food companies, and individuals to do more to improve food safety, and that it is working with nations to implement strategies.

Threats and impact vary by region

The WHO's African region had the highest burden of foodborne disease per population, followed by Southeast Asia, which had the highest absolute numbers, with 150 million illnesses and 175,000 deaths each year. The lowest burden was seen in the European region, followed by the Americas.

Specific disease threats also varied by region. For example, konzo—a paralysis caused by cyanide in cassava—is a unique threat in Africa, killing one in five people who develop the condition. In Central and South America, toxoplasmosis and pork tapeworm stood out as concerns.

Meanwhile, in the Eastern Mediterranean region, more than 195,000 people are sickened by brucellosis each year from consuming contaminated milk or cheese from infected animals, comprising half of the global cases.

In the European region, Listeria from contaminated food kills an estimated 400 people each year. And in the Western Pacific region, aflatoxin is the leading cause of foodborne illness deaths, unlike other parts of the world where diarrheal illnesses cause the most fatalities, according to the report. That region also has the highest number of deaths from foodborne parasites, especially the Chinese liver fluke.

Next steps

The WHO said the policy and social impacts of the report will be the topic of a symposium on Dec 15 and 16 hosted by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health.

In an accompanying commentary today, Kazuaki Miyagishima, MD, PhD, the WHO's director of food safety, said food safety hasn't always been a high priority for countries, especially those juggling numerous serious health challenges.

He added that the WHO is working with countries to better identify food safety challenges and has developed an online tool to help policymakers understand their specific regional threats so they can take targeted actions.

He said food safety problems have far-reaching implications that extend to food exports, tourism, and economic development.

"It is my fervent hope that this new information will foster increased political attention and spur collective action to improve food safety, help protect those who are most vulnerable, and ultimately deliver reductions in these preventable illnesses, disabilities and deaths," Miyagishima wrote.

See also:

Dec 3 WHO press release