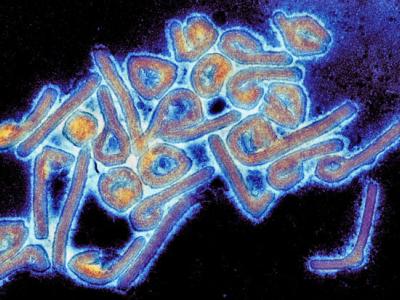

A new study explored flare-ups of Ebola in Sierra Leone in the second half of last year, which might have involved both transmission via sex and via breastmilk, while a separate report noted the heavy burden of the disease on healthcare workers (HCWs) at the height of the outbreak in that nation.

In the first study, the authors emphasized that rapid genetic sequencing of the newly emerging cases was instrumental in identifying the chains of transmission involved.

Also in recent Ebola literature, The Lancet published a detailed report on UK nurse Pauline Cafferkey, who suffered two relapses after recovering from Ebola, and US scientists reported on an Ebola survivor giving birth in California and the necessary precautions involved in her care.

Gene sequencing to track flare-ups

The study on the 2015 Ebola flare-ups involved an international team led by scientists at the University of Cambridge and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and was published last week in Virus Evolution.

Using cutting-edge real-time sequencing of Ebola virus genomes conducted in a temporary lab set up in April 2015 in Makeni, Sierra Leone, the group pieced together a detailed picture of the latter stages of the outbreak in the country, when isolated cases continued to be reported, even though all known transmission chains were believed to be tamped down. The cases included likely sexual and breastfeeding transmission.

Rapid genomic sequencing in the middle of an epidemic could help contain outbreaks by allowing public health workers to quickly trace new cases back to their source, the authors said.

The team generated 554 complete Ebola genome sequences from samples from blood, cheek swabs, semen, and breast milk collected from December 2014 to September 2015 from regions in and around Makeni. They also analyzed 1,019 samples sequenced by other groups to create a more robust picture of the Ebola virus variants in the country.

The investigators found that during 2015 at least nine separate lineages of the virus circulated in Sierra Leone, eight of which evolved from a single variant introduced into the country in June 2014. The other lineage originated in Guinea.

Starting in mid-2015, samples from all new Sierra Leone cases were rapidly sequenced in the Makeni lab. The data from these emerging cases, combined with the data already analyzed, helped public health workers locate the source of infection for some of the final Ebola cases in the country. These data revealed that some cases were acquired through unconventional transmission chains and support previously published evidence that the Ebola virus can be found in bodily fluids such as semen and breast milk and may persist beyond the standard quarantine times, the authors noted.

The case likely involving sexual spread involved a woman in Kambia who died in August 2015, 50 days after the last reported Ebola case in the region. Sequencing revealed a close match with samples obtained from a male Ebola survivor with whom she had sex not long before she died. Several other cases have been linked to sexual contact with Ebola survivors.

The researchers also detail the case of a woman infected in June 2015 who likely passed the virus to her 13-month-old baby through breastfeeding. The woman was exposed to the virus when her niece, who fled quarantine, died at her house during childbirth.

All who were present during the niece's childbirth were quarantined, and the 13-month-old tested positive for Ebola 3 days after being released from quarantine. The mother of the baby (the aunt of the woman who died) experienced no symptoms, and her blood tested negative for the virus. But her breastmilk tested positive.

Gene sequencing showed that the same variant was found in samples from the baby but differed from the virus that infected the niece. As with sexual transmission, other cases of likely spread via breastmilk have been reported.

Importance of sharing data

Matthew Cotten, PhD, joint senior author from the Sanger Institute, said in a Wellcome Trust news release, "During the epidemic, combining our Ebola virus genome sequences with data from other groups provided insight into how the virus was evolving and contributed to an important reference for tracking the source of new cases. As the outbreak progressed, our data also show that quarantines, border control and checking methods were effective, as movement of the virus within and between countries ceased."

Wellcome Trust Director Jeremy Farrar, MD, said, "Close contact with an infected individual is still by far the most common way for Ebola to spread, but this study supports previous research suggesting that the virus can persist in bodily fluids for a long time after recovery. These unusual modes of transmission may have contributed to isolated flare-ups of infections towards the end of the epidemic.

"The success of this innovative project shows how important it is to carry out genome sequencing within the affected countries, and for the data to be shared in a rapid and open way as part of the epidemic response."

Spread in healthcare settings

In the second study, researchers from the World Health Organization, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and elsewhere analyzed data from the Sierra Leone National Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Database, contact tracing records, Kenema Government Hospital (KGH), and burial logs to get a clearer picture of the impact of Ebola on HCWs during the height of the epidemic Kenema district, which reported one of the largest outbreaks in West Africa.

The team found that HCWs were much more likely to contract Ebola outside the Ebola treatment unit (ETU) than in it. Their findings appear in the May 18 early online edition of Clinical Infectious Diseases.

From May 2014 through January 2015, the investigators documented 600 Ebola cases in the district, including 92 involving HCWs, 66 of whom worked at KGH.

The researchers found that, among KGH medical staff and volunteers, 18 of 62 who worked in the ETU (29%) contracted Ebola, compared with 48 of 83 (58%) elsewhere in the hospital. Only 13% of infected HCWs reported contact with Ebola patients, while 27% reported contact with other infected HCWs.

The case-fatality rate for HCWs was 69%, compared with 74% in non-HCWs, illustrating the heavy burden of the disease in the district. The authors noted that most HCWs had exposure to the virus both inside and outside the hospital, adding that prevention steps must address that reality.

Need for vigilance in survivors

In the case report on Pauline Cafferkey, who suffered two high-profile relapses in October 2015 and February 2016, UK scientists detailed her first relapse, which involved advancing meningoencephalitis.

The team treated her with the experimental antiviral drug GS-5734, made by Gilead Sciences of San Francisco, and supportive therapy. Ebola virus RNA in her cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) slowly declined and was undetectable 14 days after GS-5734 treatment began.

The authors conclude, "Our report shows that previously unanticipated, late, severe relapses of Ebola virus can occur, in this case in the CNS. This finding fundamentally redefines what is known about the natural history of Ebola virus infection.

"Vigilance should be maintained in the thousands of Ebola survivors for cases of relapsed infection."

The second case report, published last week in Emerging Infectious Diseases, involved an Ebola survivor who had a baby in the United States. The authors, from the CDC and California, highlight infection control, protective equipment, and other measure necessary in such a situation.

They wrote, "Hospitals in the United States must be prepared to care for [Ebola] survivors."

See also:

May 18 Virus Evol study

May 18 Wellcome Trust press release

May 18 Clin Infect Dis report

May 18 Lancet case report on Cafferkey

May 19 Emerg Infect Dis case report on Ebola survivor