In the latest Zika research developments, experiments on placental cells suggest a window of vulnerability for developing fetuses, and amniotic fluid and other testing during pregnancy show that positive Zika findings can be transient, adding to surveillance challenges.

In another report, a case report on a Brazilian woman infected with Zika virus late in pregnancy found that the virus persisted in breast milk 33 days after symptom onset and 9 days after she delivered her baby.

Early extensive damage from African Zika strain

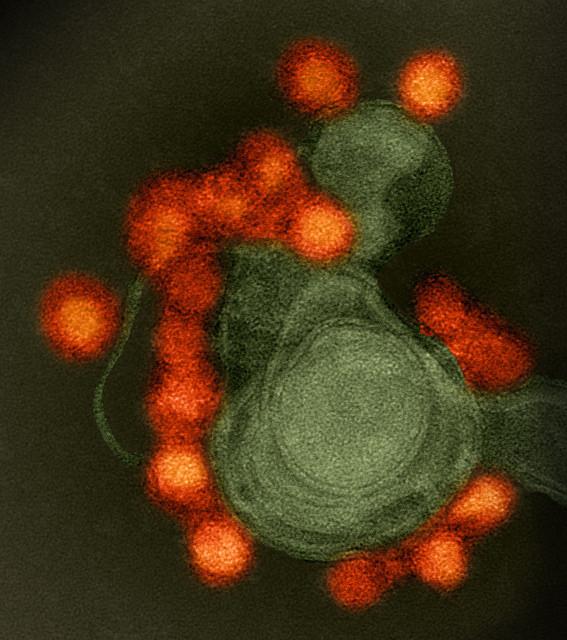

In the placental cell study, scientists looked at the susceptibility of human placental trophoblasts to Zika virus. They used cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblasts from placental villi at pregnancy term and colonies of trophoblasts from embryonic stem cells to simulate the cells at implantation phase. The team from Brazil and the University of Missouri published their findings yesterday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

They studied infection with the Asian Zika strain that has already been linked to microcephaly and other birth defects, as well as the African strain for which the threat to unborn babies is still unclear.

Cells from the term placentas resisted infection, expressing genes associated with antiviral defense. However, embryonic stem cell trophoblasts quickly became infected, produced infectious virus, and underwent lysis shortly after exposure. Surprisingly, the damage occurred after much lower-levels exposure to the African Zika strain when compared to the Asian Zika strain.

Researchers said the findings suggest that the developing fetus might be most vulnerable to Zika virus early in the first trimester, before mature villous trophoblasts become established, and that there maybe be a window of risk when the tissue is exposed to maternal blood and fluids.

Regarding the unexpected findings for the infectivity of the different Zika strains, the team said one explanation might be that the African strain is so destructive to trophoblasts surrounding the embryo that the pregnancy would terminate at an early stage, possibly without significant extension of the mother's menstrual cycle.

"On the other hand, infection with an Asian strain may be less destructive to the early placenta and allow the pregnancy to continue and fetal infection to become established," they wrote.

Study finds variability in fetal test results

The study on Zika testing is a case series of eight mothers infected during Martinique's recent outbreak and their fetuses, all of which had abnormalities on fetal ultrasound. Researchers from France and Martinique published their findings Feb 11 in the early online edition of The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

All but two of the women were symptomatic during their first trimester, and blood tests for six of them were positive for Zika at the time of referral. Fetal abnormalities were detected after 20 weeks' gestation, and amniotic fluid was initially positive at more than 10 weeks after suspected maternal infection, for all of the women. Researchers also monitored maternal and fetal blood, urine, amniotic fluid, placenta, and fetal tissues.

Repeat testing revealed that amniotic fluid became negative for two cases and fetal blood was transiently positive in six cases. Fetal blood tests also showed evidence of liver dysfunction and possibly anemia.

The group said the change in amniocentesis results over time, as well as that of the mothers' blood and urine, show there are limits of testing and the chance of possible false-negative results. They said more studies are needed to better define their use in identifying possible congenital Zika virus infections.

In related editorial in the same issue, Suzanne Serruya, MD, PhD, a reproductive health specialist with the Pan American Health Organization in Uruguay, wrote that new information about the fetal biological parameters could be incorporated into ongoing cohort studies to strengthen the diagnosis for when serology testing fails. She also said knowledge about the course of viremia could help provide better evidence for developing more precise ultrasound and amniocentesis recommendations in Zika settings.

Zika can linger in breast milk

The case report describing lingering Zika virus in breast milk involves a 28-year-old Brazilian woman who was infected during her 36th week of pregnancy. Researchers reported their findings yesterday in a letter to Emerging Infection Diseases.

Initial blood tests were positive for Zika virus. At 22 days after illness onset, blood and urine tests were negative; however, a colostrum sample was positive for Zika virus.

The baby was born healthy at 38 weeks' gestation, with no physical abnormalities and with no evidence of Zika virus in amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, placenta, or urine tests. However, the virus was still present in breast milk, and the mother was counseled not to breast feed.

Viral culture was positive for Zika virus, and the woman's breast milk was positive for Zika virus at 33 days after illness onset and 9 days after delivery.

Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations don't recommend that mothers in situations similar to the woman in the case report avoid breast feeding, the group noted. They said though no studies have confirmed Zika transmission through breast milk, more studies are needed to gauge the risk.

See also:

Feb 13 PNAS abstract

Feb 11 Lancet Infect Dis abstract

Feb 11 Lancet Infect Dis commentary

Feb 13 Emerg Infect Dis report