The source of infection for a Utah man who became ill with Zika virus after caring for another patient last summer remains a mystery, but person-to-person transmission is the most likely culprit. New details surrounding the patient's case from investigators at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and their partners in Utah appear in latest issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

For a year, the man's story has confounded Zika researchers. At age 38, he had no known risk factors for Zika besides contact with a 73-year-old family member, who contracted the virus in Mexico and died from complications several weeks later in Utah. The older man had an extremely high viral load, about 100,000 times higher than others with Zika.

The younger man had no sexual contact with anyone who had recently a Zika-endemic area. He fully recovered from Zika after about 12 days of symptoms.

At this time, experts believe Zika is only transmitted one of five ways: via an infected mosquito, sexual intercourse, to a fetus via an infected mother, or through blood transfusion or lab exposure. Thus, the Utah man's infection was perplexing.

Authorities tested seven species of mosquitoes collected from hundreds of pools near the man's home; none had Zika virus.

Close contact, but no others infected

Several family members reported similar interactions with the index patient, but they did not contract the virus: They reported kissing, hugging, and helping clean up vomit and stool, but no contact with bodily fluids. The CDC tested a total of 19 family members who met the definition of contact and none had Zika except the patient.

"During hospitalization of the index patient, patient A reported staying for 2 days and nights (>48 hours) in his room in the intensive care unit (ICU) and reported hugging, kissing, and touching him frequently," the authors describe.

Hospital workers were also traced and followed to see if their similar patterns of contact resulted in Zika infection. None of the 86 healthcare workers who provided blood samples for testing had Zika.

"None of the other family members became infected, despite similar or more frequent and direct contact with the index patient during his viremic period. No healthcare personnel became infected despite the index patient having substantial invasive procedures and moderate production of body fluids," the authors wrote. "Overall, our findings suggest the infection of patient A represents a rare transmission event through unknown, but likely, person-to-person mechanisms."

Though rare, the case of the Utah man means person-to-person contact may occur through casual or familial exposure, especially in the case of an index patient with high viral loads. They said more research is needed to determine the infection risk from different body fluids and host factors that might increase susceptibility to infection.

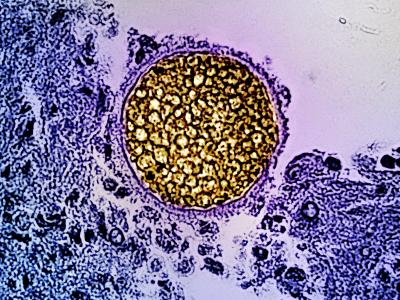

Zika virus attacks human brain endothelial cells

Finally today, a new study in the journal mBio describes how the Zika virus infects and invades human brain endothelial cells, which normally help protect neurons from viruses. This understanding could help explain why fetuses exposed to maternal Zika have so many congenital disorders, the most severe of which is microcephaly.

The researchers found Zika virus can hide out and replicate in endothelial cells before they are released basolaterally. This would provide a direct mechanism for Zika to cross the blood-brain barrier. This action happens within the first 9 days of infection, the authors said.

See also:

Jul 11 Emerg Infect Dis study

Jul 11 mBio study