In parts of Ethiopia with heavy burdens of trachoma, the world's leading infectious cause of blindness, long-term mass treatment of children with azithromycin kept the disease at a low level but did not eliminate it, according to a study described today in PLoS Medicine.

The 3-year-study followed a 4-year trial of azithromycin treatment to prevent trachoma in Ethiopian children. The new study showed that trachoma prevalence remained low and stable in communities where annual or semiannual treatment continued but that it increased in communities where the antibiotic was stopped.

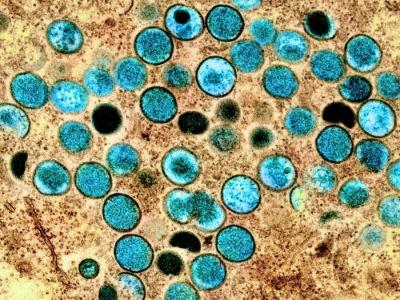

Trachoma is caused by ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Mass distribution of azithromycin is a key part of the World Health Organization's strategy for controlling trachoma, called SAFE (surgery for trichiasis, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvements), the new report notes.

The authors, from the University of California San Francisco and offices of the Carter Center in Atlanta and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, say trachoma is disappearing globally but is still deeply entrenched in some areas of Ethiopia. Mass distribution of azithromycin reduces the disease to low levels, but eliminating it has proved difficult.

Keep on treating, or not?

The researchers aimed to find out if mass azithromycin treatment could be safely stopped after 4 years in areas of northern Ethiopia where the disease is common.

In the previous trial, called TANA I, 48 communities were randomly assigned to receive either annual or semiannual (twice yearly) mass azithromycin treatments for children (0 to 9 years old) from 2006 to 2009. The prevalence of C trachomatis infection dropped over that time from 41.9% to 1.9% in the annual treatment group and from 38.3% to 3.2% in the semiannual group.

The new trial, TANA II, ran from 2010 to 2013 and targeted a subset of communities that had been involved in TANA I. They were randomly assigned to continuation or cessation of treatment, and children in the continuation arm were offered either annual or semiannual treatment with one directly observed dose of azithromycin. The second trial started about 11 months after the end of the first one.

At the end of 3 years, the authors assessed the prevalence of ocular chlamydial infection in a random sample of children in each arm of the trial. In comparing the end-of-trial prevalence in the two arms, they used a model that adjusted for the baseline prevalence. Mean antibiotic coverage in the treatment communities was more than 90% throughout the trial.

In the areas where treatment was stopped, the mean prevalence of infection in children rose from 8.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2%-12.4%) at the start of the trial to 14.7% (95% CI, 8.7%-20.8%; P = .04) at the end, the report says. In communities where treatment continued, the mean prevalence of infection dropped slightly, from 7.2% (95% CI, 3.3%-11.0%) at the beginning to 6.6% (95% CI, 1.1%-12.0%, P = .64) by the end.

The difference in ocular chlamydia prevalence between the two arms at the end of the trial was significant (P = .03), the researchers found. They also found that infection prevalence at 3 years was slightly but not significantly higher in communities that received annual treatment versus those with semiannual treatment (9.3% versus 3.3%; P = .09).

Seven treatment rounds not enough

Although areas with continued treatment ended up with lower levels of infection than those where treatment stopped, "this study demonstrates that even 7 rounds of mass azithromycin were not sufficient for elimination in an area with hyperendemic trachoma," the authors comment. They said this aligns with previous research in which the use of topical tetracycline ointment suggested that trachoma could not be eliminated by antibiotics alone.

The authors suggested several possible explanations for the failure to eliminate trachoma, including "relatively poor water and sanitation" and introduction of infection by residents who did not participate in the treatment program.

On the positive side, the authors said communities where treatment was stopped had slower rates of disease resurgence than were seen in previous studies in heavily affected areas of Ethiopia.

Among the study's limitations are that it did not involve a combined strategy, such as azithromycin plus facial cleanliness, and it probably can't be generalized to areas with lower trachoma burdens, the researchers said.

They commented that long-term mass use of azithromycin may promote resistance to macrolide antibiotics. Previous studies have not shown this with C trachomatis, but they were very limited, and mass use of azithromycin for trachoma has been shown to foster macrolide resistance in non-target microbes, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. It may be important to monitor macrolide resistance and its effect on results in communities where long-term mass azithromycin treatment is used, the researchers said.

In a summary of their report, the authors said trachoma may become the first human bacterial disease to be eliminated by a public health program, but "these results indicate that stopping mass azithromycin treatment in some severely affected areas is not realistic. Alternative strategies for trachoma elimination may be required for the most severely affected areas."

See also:

Aug 14 PLoS Med report

Aug 14 PLoS press release