Biopharmaceutical company Achaogen announced yesterday that it's filing for bankruptcy, a move that antibiotic development advocates say is further evidence of the need for new incentives and payment models for a broken antibiotic market.

In a press release yesterday, the company said it has filed a voluntary petition under Chapter 11 of the US bankruptcy code, as well as a motion seeking authorization to sell off company assets under Section 363 of the code.

"The Achaogen board of directors and management team have thoroughly assessed our strategic options and financial situation and unanimously agree that this structured sale process represents the best possible solution for the company," Achaogen CEO Blake Wise said. The company is headquartered in South San Francisco, California.

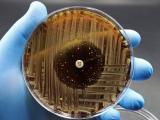

Achaogen's antibiotic plazomicin was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in June 2018 for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and is seen as an important option for treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections, which are among the most difficult bacterial infections to treat. The company also had other antibacterial products in its pipeline.

Still, Achaogen was not making enough of a profit to stay afloat. And antibiotic development advocates say that's a bad sign for the few companies working on new antibiotics.

"The Achaogen bankruptcy is dire news," Allan Coukell, senior director of health programs at the Pew Charitable Trusts, told CIDRAP News. "The end of Achaogen as an antibiotic-focused research-and-development organization is bad. But it also makes the larger point that even a company that succeeds in bringing an innovative new antibiotic to market can't necessarily survive."

"We're worried that Achaogen is not alone, and that we will see the fall of other small antibiotic manufacturers," said Helen Boucher, MD, director of the Tufts Integrated Center for Management of Antibiotic Resistance and treasurer of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). "And we're worried about the danger this could present for our patients."

New incentives needed

The Pew Charitable Trusts and IDSA were among a coalition of groups that sent a letter to US lawmakers in February urging them to pass a package of incentives to help jumpstart the development of critically needed antibiotics. The letter suggested the package could include a mix of tax incentives, novel "pull" incentives that increase the value of new antibiotics, and changes in how pharmaceutical companies are reimbursed for antibiotics.

"We've been concerned about this for some time," Boucher said. "We've worked very hard to sound the alarm about antibiotic resistance and the need for a robust and renewable pipeline."

While the National Institutes of Health, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) have helped companies like Achaogen with financial "push" incentives to get them through the early stages of antibiotic development—Achaogen received $2.4 million from CARB-X in April 2018 for the development of a new aminoglycoside—advocates say that "pull" incentives are needed to ensure that new antibiotics will be profitable and that drug makers will continue developing and producing them.

Among the ideas that have been suggested is a $1 billion market entry reward that would be paid out over 5 years to pharmaceutical companies for regulatory approval of an antibiotic that addresses a defined public health need. Other ideas include granting vouchers that would allow companies that develop new antibiotics to extend the exclusivity period on more profitable drugs in their portfolio.

Changing the payment model for antibiotics is also seen as critical. Under the current drug reimbursement model, pharmaceutical company profits are based on volume of drugs sold. That's a suitable model for drugs for chronic conditions, but—as Coukell and other antibiotic development advocates point out—antibiotics are different from most other drugs because patients take them for only a short period.

In addition, when a company develops a new antibiotic, clinicians want to keep it on the shelf until other options are exhausted, in order to slow the development of resistance. That makes it difficult for companies to make money on new antibiotics. And for small companies like Achaogen, the lack of return drives away much-needed investors.

"The antibiotic market is broken and will not fix itself," Coukell said. "Policymakers must take this as a clarion call to act now."

According to Pew, over 90% of the antibacterial products in development today are from small companies, and over 60% of these companies have no other products on the market.

"These companies are not making money," Boucher said. "Our hope is to engage legislators about how antibiotics are different and need to be considered in a different way. Every citizen needs these medicines."

See also:

Apr 15 Achaogen press release

Feb 6 CIDRAP News story "Letter urges congressional action to stimulate antibiotic development"