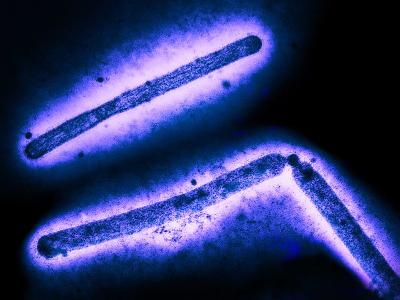

In a report last week, researchers described the first human in the United States known to be bitten by an Asian longhorned tick, a rapidly spreading invasive species that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned about last year.

Though the 66-year-old man did not get sick, scientists know that Haemaphysalis longicornis can harbor bacteria that can cause human and animal diseases—possibly including Lyme disease—and an investigation into areas where the man lived found the tick in locations other ticks aren't typically found, which could lead to changes in public health risk messaging.

A team from the CDC, New York, and New Jersey reported the findings on May 31 in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

The tick was found in the United States for the first time in 2017 on a sheep in New Jersey, and since then, the species has been found in at least 10 states, mainly in the eastern states but also Arkansas. It's still not known how widespread Asian longhorned ticks are in the United States, but health officials are worried, because they are aggressive biters.

Females can produce massive numbers of offspring without mating, and in some parts of the world—such as New Zealand and Australia—the species have reduced production in dairy cattle by 25%.

Ticks found on sunny lawns

According to the new report, a 66-year-old man from Yonkers, New York, removed a tick from his leg in June 2018. He had not traveled outside his home county for the past 30 days, and his only outdoor exposure was his lawn and one other lawn in the same area. His doctor prescribed him a single 200-milligram dose of doxycycline, presuming that the tick was Ixodes scapularis, the most common US Lyme vector.

Later that day, the patient took the tick to the Lyme Disease Diagnostic Center in Westchester, New York. He didn't have any symptoms at the time and didn't get sick over the next 3 months.

Testing in New York identified the tick as an Asian longhorned tick nymph, with genetic sequencing adding more evidence affirming the finding. The National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa, further confirmed the finding.

Tick sampling using corduroy drag cloths found Asian longhorned ticks on the patient's manicured lawn, some of them in direct sun. More were found in the park across the street from the patient's house, both in open, cut grass exposed to direct sun and in taller, shaded grass next to the woods. Testing also found ticks on a nearby public trail, in mowed short and midlength grass near the trail edge, both in full sun and partial shade. The discovery of the ticks near the man's house were the first known collections in New York state.

The authors wrote that finding the ticks on manicured lawns and in open sun may be significant, because public education efforts often stress that Ixodes scapularis ticks—the most common biting tick in New York state—are found in wooded areas or shaded grass.

Next steps for ongoing threat

In a related editorial in the same issue, Bobbi Pritt, MD, MSC, with the division of clinical microbiology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, wrote that though the report of a human bite isn't surprising, it proves that the invasive longhorned tick continues to bite hosts in its newest location.

"This is extremely worrisome for several reasons," she wrote. One reason is that Asian longhorned ticks can carry several important human pathogens, including the potentially fatal severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) virus and Rickettsia japonica, which cases Japanese spotted fever. "While these pathogens have yet to be found in the United States, there is a risk of their future introduction," she added.

Also, Pritt said several other human pathogens have been detected in the ticks, but it's not clear the Asian longhorned species are able to transmit them to humans. They include Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia, and Borrelia species. Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria.

She warned that the organisms are present in states where longhorned ticks have been found and that it's possible that the tick—known to be an aggressive biter—might be able to transmit Heartland virus, given its close relationship to SFTS virus.

Pritt said it's clear that the invasive species is here to stay for the foreseeable future, and next steps should include public awareness campaigns that incorporate the new information, easy-to-use resources for labs to identify the tick, and more research to understand the implications of the new findings.

See also:

May 31 Clin Infect Dis abstract

May 31 Clin Infect Dis commentary

Nov 30, 2018, CIDRAP News story "CDC: Worrisome longhorned tick spreading rapidly in US"