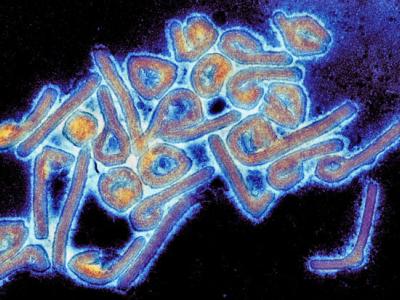

A new analysis of US hospital data has found that hospital-wide use of certain classes of antibiotics is linked to increases in hospital-associated Clostridioides difficile infection (HA CDI).

The study, published this week in Infection Control and Epidemiology, found that for every 100-day increase in the use of four antibiotic classes—cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and lincosamides—there was a 12% increase in HA CDI. Although many antibiotics are associated with increased risk of CDI because they can disrupt normal gut bacteria and allow C difficile to flourish, these four classes have been deemed "high risk" in C difficile practice guidelines, based on previous research.

C difficile is the most common cause of healthcare-associated infection and diarrhea in the United States, responsible for approximately half a million infections and 30,000 deaths a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It costs the US healthcare system roughly $5 billion a year.

Tracking hospital high-risk antibiotic use

To get a better sense of how these antibiotics are impacting HA CDI rates, a team of researchers from the CDC; Becton, Dickinson and Company; and Nabriva Therapeutics looked at microbiologic and pharmacy data from 171 US community and teaching hospitals from June 2016 through July 2017, focusing on the combined use of the four high-risk antibiotics, with additional evaluation of the four classes individually.

Hospital-level use was measured as days of therapy (DOT) per 1,000 days present (DP).

Multivariable analysis estimated the relative risk (RR) of these antibiotics on HA CDI while controlling for other risk factors, such as community CDI pressure, length of hospital stay, proportion of elderly patients, and hospital characteristics.

The median use of the high-risk antibiotics across the 171 hospitals was 241.2 DOT per 1,000 DP. The most frequently used high-risk antibiotics were cephalosporins (47.9%), followed by fluoroquinolones (31.6%), carbapenems (13.0%), and lincosamides (7.6%). The median HA CDI rate across the hospitals was 33 per 10,000 admissions.

The overall correlation between high-risk antibiotic use and HA CDI was 0.22 (P = .003), with a higher correlation observed in teaching hospitals (0.38; P = .002) than in non-teaching hospitals (0.19; P = .055). When each class of high-risk antibiotics was evaluated individually, only cephalosporins were significantly correlated with HA CDI (0.23; P < .01).

When other risk factors were accounted for, combined high-risk antibiotic use was independently associated with a significant risk for HA CDI, with an RR of 1.12 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04 to 1.21, P = .002) for every 100-day increase of DOT per DP. Other factors independently associated with HA CDI rates included larger proportions of patients over 65 years of age, higher rates of community-associated CDI, longer hospital stays, and hospital teaching status.

Possible help for low-resource settings

The authors of the study say the findings illustrate the clinical relevance of tracking hospital-level use of high-risk antibiotics for CDI, and could help resource-limited C difficile reduction and antimicrobial stewardship programs by narrowing their focus. They note that programs specifically targeting cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone use have been linked to CDI reductions in the United Kingdom.

They also note that the lack of association between three of the individual classes of antibiotic and HA CDI rates may reflect changes in antibiotic use spurred by antibiotic stewardship programs, which have been in place in US hospitals for several years now.

They conclude, "Future studies would ideally combine both facility- and patient-level measures of high-risk and total antibiotic use to further inform CDI mitigation strategies."

See also:

Sep 16 Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol abstract