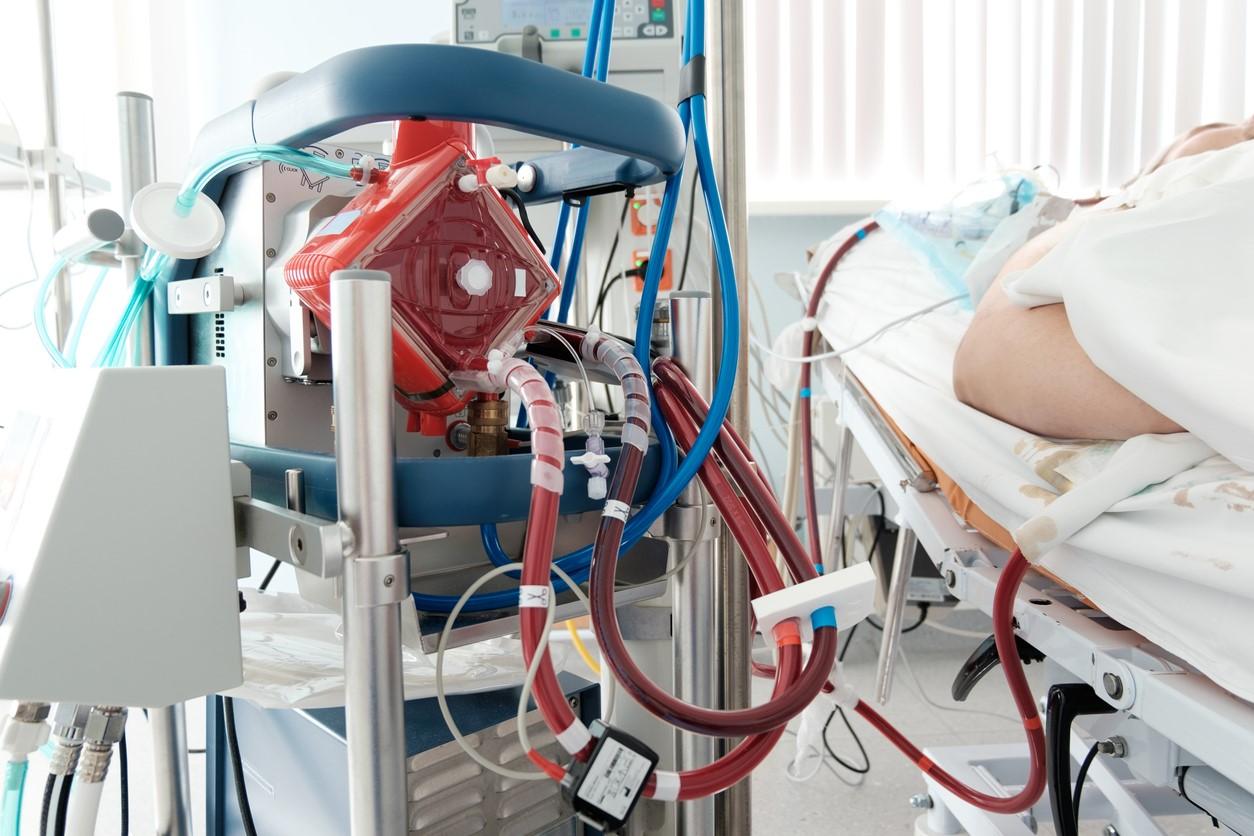

Nearly 90% of adult COVID-19 patients who were eligible for—but didn't receive—extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) during the height of the pandemic died in the hospital owing to a lack of resources, even though they were young and had few underlying health issues, according to a natural experiment published late last week in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Reserved for youngest, sickest

Vanderbilt University researchers prospectively analyzed data from all COVID-19 patients referred to a single center for ECMO from Jan 1 to Aug 31, 2021. Patients qualified for ECMO if they were younger than 60 years, had a body mass index (BMI) less than 55 kg/m2, had received mechanical ventilation for more than 7 days, or had irreversible neurologic injury, chronic lung disease, cancer, or advanced multi-organ dysfunction.

Patients also had to have no more than three selected contraindications, including age older than 50 years, BMI greater than 45 kg/m2, underlying illnesses, receipt of mechanical ventilation for more than 4 days, acute kidney injury, receipt of vasopressors (drugs used to treat low blood pressure), hospitalization for more than 14 days, or a period of more than 4 weeks since COVID-19 diagnosis.

A systematic assessment of the health system's resources to provide ECMO for eligible patients (ie, equipment, personnel, and intensive care unit bed availability) was conducted. If resources were available, patients were started on ECMO and then transferred to an ECMO center, but patients were not referred if resources were already at capacity. Patients transferred to other regional ECMO centers were started on the treatment after arrival at the ECMO facility.

"Even when saving ECMO for the youngest, healthiest and sickest patients, we could only provide it to a fraction of patients who qualified for it," lead author Whitney Gannon, MSN, MS, said in a Vanderbilt news release. "I hope these data encourage hospitals and federal authorities to invest in the capacity to provide ECMO to more patients."

61% of patients didn't receive ECMO

The health system didn't maintain a waiting list for ECMO because of the short eligibility window for ECMO after tracheal intubation and the long average length of ECMO for patients already receiving the treatment.

Among 240 COVID-19 patients referred for ECMO, 26 (10.8%) didn't complete the referral evaluation, 44 (18.3%) didn't meet the criteria for severity of lung injury, 80 (33.3%) had contraindications to treatment, and 90 (37.5%) were eligible for ECMO. Median patient age was 40 years, and 27.8% were female.

Fifty-five patients (61.1%) were not transferred to an ECMO facility and didn't receive the therapy because of a shortage of resources. Forty-nine of these patients (89.1%) died in the hospital, versus 15 of 35 patients (42.9%) who received ECMO (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.23; 95% confidence interval, 0.12 to 0.43).

The health system had ECMO capacity for 35 patients (38.9%), of whom 24 were started on the treatment at the hospital before transfer to an ECMO facility, while 11 were transferred to another regional center. Eight of the 11 patients were started on treatment after arrival at the center, and 3 died or developed a contraindication to ECMO after arrival but before treatment was started. Characteristics of both groups of patients were similar at the time of referral.

Senior author Jonathan Casey, MD, said that the study adds evidence that ECMO works. "Because some patients die despite receiving ECMO, there has been debate about how much benefit it provides," he said. "This study shows the answer is a huge benefit. This data suggests that, on average, providing ECMO to two patients will save a life and give a young person the potential to live for decades."

Coauthor Matthew Semler, MD, said that many people not working in medicine during the pandemic struggled to understand the reality of "strained" or "overwhelmed" hospitals. "This article helps make those effects tangible," he said. "When the number of patients with COVID-19 exceeds hospital resources, young, healthy Americans die who otherwise would have lived."