Today marks World Malaria Day, which since 2007 has focused attention on building support for control strategies in the hardest-hit countries, and along with statements of support come two new studies, one on steps that decreased the artemisinin-resistant form of the disease in Myanmar and the other adding more evidence to methylene blue as a potential treatment.

The theme of this year's campaign is "Ready to Beat Malaria," which emphasizes the need to intensify efforts to battle the disease. Though much progress has been made in reducing deaths and infections since 2000, progress has stalled in some regions, especially those experiencing political upheaval.

In a statement, Matshidiso Moeti, MD, World Health Organization regional director for Africa, said, "I urge countries to allocate adequate resources and to work across sectors and strengthen cross-border collaboration. With the required resources, strong coordination and dedicated partners, we can accelerate our actions to achieve a malaria-free Africa. We are ready to beat malaria."

Also, two officials from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) said that, as a global community, the world can't afford to surrender the gains made toward controlling and eliminating malaria. The officials are B. Fenton Hall, MD, PhD, chief of the parasitology and international programs branch, and NIAID Director Anthony Fauci, MD.

Myanmar interventions stabilized drug resistance

In the Myanmar study, researchers from Thailand and the University of Oxford analyzed the impact of scaled-up drug administration plus early diagnosis and treatment in four townships in eastern Myanmar that have proved challenging.

The area not only has a hilly, remote, and forested terrain, it is marked by a complex political situation and has a malaria season in which artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum circulates. The team published its findings yesterday in an early online edition of The Lancet.

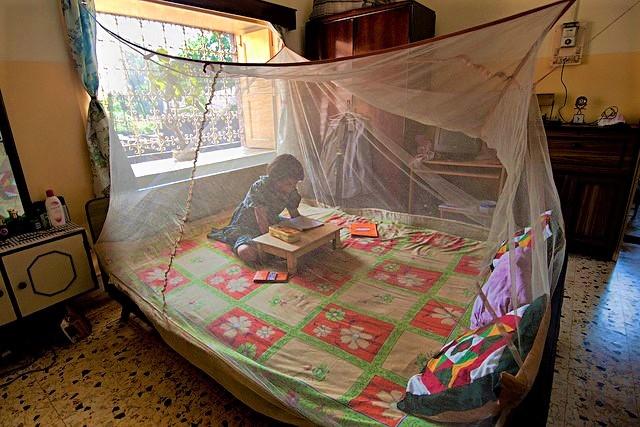

From May 2014 through April 2017, villages were provided community-based malaria posts offering rapid diagnostic testing and treatment with artemether-lumefantrine plus single low-dose primaquine. During each survey period, the researchers obtained blood samples from randomly selected adults. People in 50 areas identified as malaria hot spots, which had a three-time higher incidence than neighboring villages, were targeted with mass drug administration of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine plus single-dose primaquine once a month for 3 consecutive months.

One year later, the team measured malaria levels in the hot spots. Early diagnosis and treatment was associated with a significant malaria decrease in the hot spots, and the researchers also found that mass drug administration in those areas led to a fivefold decrease in malaria infections. Incidence of P falciparum declined by between 60% and 98% across the villages, with P vivax malaria decreasing between 52% and 93%.

By April 2017, 79% of the 1,222 villages were free of malaria for at least 6 months, and the prevalence of markers for artemisinin resistance was stable over the 3-year study period.

The team concluded that early diagnosis and effective treatment substantially decreased drug-resistant malaria, even in remote, politically sensitive parts of Myanmar, adding that targeted mass drug administration tamped down malaria incidence in the hot spots.

"If these activities could proceed in all contiguous endemic areas in addition to standard control programmes already implemented, there is a possibility of subnational elimination of P falciparum," they wrote.

In a related commentary, Azra Ghani, PhD, with the MCR Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis in London, wrote that, because of the study's observational design, several questions remain unanswered, such as whether early diagnosis and treatment alone could have achieved similar reductions and how to define a hot spot and its role in sustaining transmission.

Also, she said the benefit of targeted treatment at hot spots may decline over time, but during that time frame the reductions would likely reduce the workload for staff at malaria posts, possibly enhancing the effect of early diagnosis and treatment. Large-scale mass drug administration can be expensive, but might have wider benefits of freeing up health workers, she added.

"Further research to understanding this balance will help to determine the appropriateness of targeted mass drug administration as a tool to aid malaria elimination," Ghani wrote.

Promise for methylene blue

The antimalarial effects of methylene blue have been known since the 1890s, but its use as single therapy has been hampered by reports of suboptimal clinical efficacy and its capacity to turn skin and urine blue. A meta-analysis published today in BMC Medicine from German researchers found that it was consistently reported to be highly effective in all endemic areas, though it was linked to mild urogenital and gastrointestinal symptoms.

The report follows a phase 2 study published in February that found the dye is safe and can kill malaria parasites more quickly than other drugs.

For the new systematic review, the researchers focused on 21 studies that among them had data on 1,504 patients, two thirds of whom were children. Older studies focused on methylene blue as monotherapy, but newer ones covered the drug as part of combination therapy. Of case reports and case series that looked at monotherapy, efficacy was high at 91%, with treatment failures attributed to unsuccessful quinine treatment, vomiting, and low and/or short dosing.

Studies suggested that methylene blue had a strong effect on P falciparum gametocyte reduction and acted synergistically with artemisinin, but not with chloroquine. Overall, the investigators found that that methylene blue was usually well tolerated with mild and typically self-limited gastrointestinal and urogenital symptoms.

They concluded that the dye may be an alternative to primaquine for addressing post-treatment infectivity in P falciparum infections and could prove to be a useful partner for triple-combination therapy regimens designed to preserve artemisinin and reduce the spread of drug-resistant parasites.

See also:

Apr 25 WHO African regional office statement

Apr 25 NIH statement

Apr 24 Lancet abstract

Apr 24 Lancet commentary

Apr 25 BMC Med abstract

Feb 6 CIDRAP News scan "Study: Blue dye shows promise for preventing malaria transmission"