New estimates of flu vaccine effectiveness during the United States' 2018-19 season based on data from surveillance and information on ambulatory patients at five sites found that the predominance of H3N2 clade 3C.3a viruses late in the season decreased vaccine effectiveness (VE).

A team led by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention researchers published its findings today in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

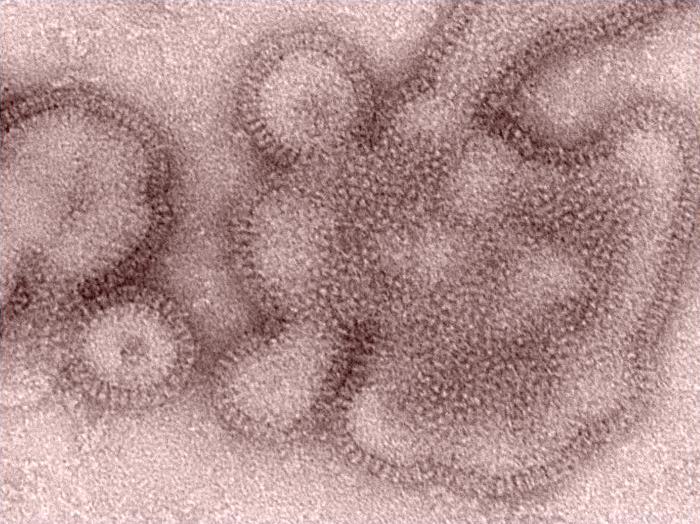

The 2018-19 season was unusual, because the 2009 H1N1 virus predominated during the first part of the season, with low levels of H3N2 that was similar to the vaccine component. During the latter part of the season, however, a drifted H3N2 variant emerged from the 3C.3a clade, which decreased protection from the vaccine. Also, very little influenza B circulated during the season.

94% of H3N2 viruses were variants

For the study, the group analyzed flu surveillance data and genetic sequencing data from flu samples collected from 2,763 patients at five clinics that are part of the VE Network. Of the group, 48% were infected with 2009 H1N1 and 49% were sickened by H3N2. The 3C.ca clade made up 94% of sequenced H3N2 viruses.

The group estimated that VE was 44% (95% confidence interval [CI], 38% to 51%) against 2009 H1N1 viruses and 9% (95% CI, -4% to 20%) against H3N2 viruses.

VE, however dropped even more for the antigenically drifted H3N2 strain, with an estimate of 5% (95% CI, -10% to 19%). And VE for any H3N2 strain did not rise to the level of statistical significance.

The investigators said the preliminary estimates—showing a rapid increase in clade 3C.3a circulation in the United States—were shared with the World Health Organization before its advisory group made its strain selections for the Northern Hemisphere's 2019-20 season, which helped support the selection of a H3N2 vaccine virus from the emerging clade. The authors concluded that experience from last flu season highlight recent challenges with H3N2 VE and the need for more broadly protective vaccines.

Complex virus-host dynamics

In a related commentary in the same issue, two experts from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston said H3N2 viruses have circulated since 1968, and many different antigenic variants have arisen. And even though flu surveillances has expanded and more information is available to characterize viruses, strain selection is complicated by complex and incompletely understood interactions between virus and host that impact emerging viruses. The experts are Robert Atmar, MD, and Wendy Keitel, MD.

They wrote that the simple answer for solving the dilemma is making better flu vaccines, but they acknowledge that it's not an easy task. Along with a host of strategies under investigation, one worth considering is adding a second H3N2 strain to the vaccine, similar to what is done with some veterinary flu vaccines and what was done for influenza B strains.

Also, Atmar and Keitel warned that flu vaccine improvements—for example, issues that cropped up with the live attenuated influenza vaccine—don't always lead to continued success. They emphasized that flu VE networks help flag when problems arise and added that reports such as the new study serve as a reminder that development of flu vaccines is a race against the clock.

See also:

Oct 30 J Infect Dis abstract

Oct 30 J Infect Dis commentary