Two new studies highlight the substantial burden of diarrheal diseases across Africa and the globe, with an especially profound impact on the very young and very old.

The first study, published today in the New England Journal of Medicine, focuses exclusively on young children. By using maps that marked rates of diarrheal diseases in 5-kilometer by 5-kilometer units, researchers have been able to produce a bird's eye view of intestinal illness in Africa.

They note that more than half of the 330,000 childhood deaths attributable to diarrhea in 2015 took place in just 55 out of 782 African states, provinces, or regions.

Mostly lower rates over 16 years

The researchers produced high-resolution maps of illnesses from 2000 through 2015. The study includes diarrheal illnesses in children under the age of 5 in 55 of Africa's 57 countries (island nations Mauritius and Seychelles were excluded).

"Diarrhea is highly preventable, and tens of thousands of child deaths from diarrhea could be averted each year if interventions targeted mortality hot spots across Africa," said Bobby Reiner, PhD, lead author and assistant professor of health metrics sciences at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, in a press release.

Overall, most countries noted a reduction of diarrheal activity between 2000 to 2015, but the burden of diseases was distributed unequally across the continent.

According to the study, 9.4% of all the severe cases of diarrhea (2.8 million cases; 95% credible interval, 2.39 million to 3.3 million) in 2015 occurred in two countries: Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Nigeria had the most variance of disease rates among African countries, with estimates ranging from 1.6 deaths per 1,000 children in Bayelsa state in the southwest to 9.5 deaths per 1,000 in Yobe state in the northeast. Certain parts of the Central African Republic, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe saw disease increases over the 15 years.

The highest diarrhea-related case fatality rates in Africa were in Lesotho (18 cases per 10,000 children; 95% credible interval, 12 to 25), Mali (17, 12 to 24), Sierra Leone (16, 11 to 23), Benin (16, 11 to 21), and Nigeria (16, 11 to 21).

The authors suggest targeted interventions in diarrheal hot spots to reduce disease burden, and note that while the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine has likely reduced diarrhea incidence, the fraction of diarrhea cases attributed to rotavirus varies across Africa (6.5 to 64.2% in 2016).

"Local estimates of diarrheal burden can be used to prioritize improved access to safe water and sanitation, which varies greatly between dense and sparse populations; childhood-growth monitoring, which has improved in most regions of Africa but not universally; delivery and uptake of vaccines, including the rotavirus vaccine; and access to diarrheal care and prevention interventions for marginalized populations that live in remote regions or in areas of conflict," the authors conclude.

Children aren't only at-risk group

In The Lancet Infectious Diseases, meanwhile, new estimates from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study in 2016 also highlight the challenges in reducing the burden of diarrhea. The study takes into account 290,310 new mortality and 5,695 new morbidity datapoints from 2015 to 2016 and involved 195 countries.

Though children under the age of 5 represent a significant proportion of diarrhea patients, adults over the age of 70 are most likely to suffer from fatal, but preventable, diarrhea illness, the study authors said.

The highest rate of diarrhea mortality among children younger than 5 years occurred in Chad (499 deaths per 100,000), the Central African Republic (384.2 deaths), and Niger (376). In contrast, diarrhea deaths among adults older than 70 years were highest in Kenya (1,877 deaths per 100,000), Central African Republic (1,282), and India (1,013).

In 2016, diarrhea was the eighth leading cause of death among all ages (1,655,944 deaths; 95% uncertainty interval [UI], 1,244,073–2,366,552) and the fifth leading cause of death among children younger than 5 years (446,000 deaths; 390,894–504,613).

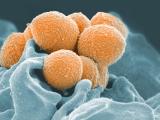

The authors suggest the rotavirus vaccine is underused globally, noting that rotavirus diarrhea remains the commonest cause of death in children younger than 5 years due to diarrhea (20.3 deaths [95% UI, 16.6–24.5] per 100,000). The most common cause of diarrhea in elderly people was shigella, causing 18.4 deaths (95% UI, 10.5–31.8) per 100,000.

Older people are also more likely to suffer from Clostridium difficile infections in high-income countries. The authors said C diff might, "explain some of the increasing diarrhoea mortality because this bacterium is difficult to treat, is often resistant to antibiotics, and is frequently associated with nosocomial and retirement home outbreaks."

Substantial impact of respiratory illness, too

Also in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, the GBD 2016 Lower Respiratory Infections Collaborators published estimates of the morbidity and mortality from those infections across 195 nations.

The authors provided estimates for the disease burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). S penumoniae contributed to more than 1 million deaths in 2016, more than H influenzae type b, influenza, and RSV combined.

Lower respiratory infections were a leading global infectious cause of mortality in all age-groups (2,377,697 deaths; 95% UI 2,145,584–2,512,809), including in children younger than 5 years (652,572 deaths, 586,475–720,612) and among adults older than 70 years (1,080,958 deaths, 943,749–1,170,638).

Malnutrition and childhood wasting remained the leading risk factor for lower respiratory infection mortality among children younger than 5, responsible for 61.4% of lower respiratory infection deaths in 2016 (95% UI 45.7–69.6), the authors said.

More than half of all lower respiratory deaths in 2016 were caused by bacteria, and increased use of antibiotics in targeted countries could be a useful intervention, the investigators said.

"We estimate that increased antibiotic availability could still prevent 30.2% (95% UI, 14.4–43.8) of lower respiratory infection deaths. However, appropriate antibiotic use remains challenging—in large part because of the absence of reliable clinical signs and symptoms that can accurately predict bacterial pneumonia—and universal use of antibiotics for lower respiratory infections could lead to antimicrobial resistance."

See also

Sep 20 N Engl J of Med study

Sep 19 University of Washington press release

Sep 19 Lancet Infect Dis diarrhea study

Sep 19 Lancet Infect Dis diarrhea commentary

Sep 19 Lancet Infect Dis respiratorystudy

Sep 19 Lancet Infect Dis respiratory commentary