The news about the antibiotic development in recent years has been, for lack of a better word, rather bleak.

Many large pharmaceutical companies have abandoned antibiotic research and development (R&D) because of the poor return on investment. Smaller companies have gone bankrupt after getting a new antibiotic approved, for the very same reason. Multiple analyses have found that the pipeline to replace some of the antibiotics we've relied on for decades has some very good candidates for deadly, multidrug-resistant pathogens, but not enough. And too few of them are truly innovative.

The science is not the issue, experts say. The big problem is the lack of a viable market for new antibiotics, one that reimburses antibiotic developers for the public health value of their product. Without that, small companies are having a difficult time attracting the type of investment they need to not only bring new antibiotics to market but merely to survive.

That's the issue that the AMR Action Fund is trying to address. Launched in June 2020 by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Association and backed by large pharmaceutical companies, with additional support from other stakeholders, the fund will invest more than $1 billion over the next several years to help bring much-needed new antibiotics to market. It also aims to help create market conditions that will enable sustainable antibiotic R&D.

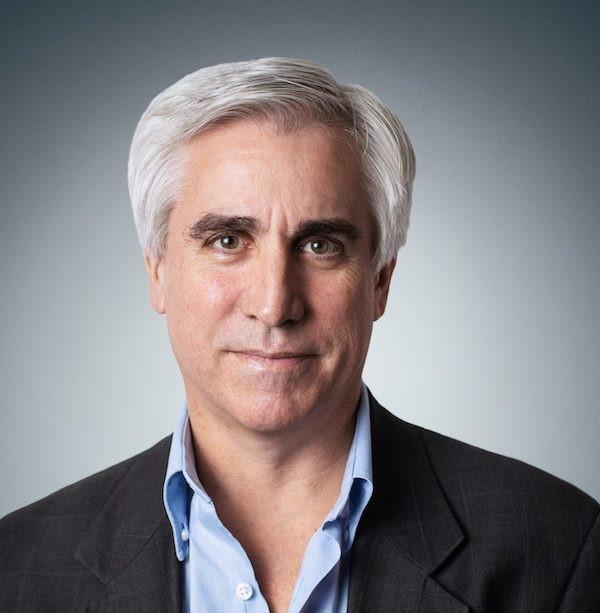

CIDRAP News spoke with AMR Action Fund CEO Henry Skinner, PhD, about the current state of antibiotic development, the need to fix the broken market for new antibiotics, and how to build a sustainable pipeline. The following excerpts from the conversation have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

CIDRAP News: When the AMR Action Fund was launched in 2020, one of the stated goals was to bring two to four new antibiotics to market by 2030. Is that still the stated goal of the fund? And how important is it that at least some of those new antibiotics, if not all of them, be truly innovative and a new class of antibiotics?

Henry Skinner: I think a new class offers several advantages, and some unknowns. To bring a new class to market, presumably, the reservoir of resistance is less. Your risk of lateral transfer of resistance, of developing resistance before you've even gotten to the drug launch…all those things should be reduced. And those are big pluses, right? That presumably means that the therapeutic will have broad activity longer [and] greater utility over a longer period of time. On the other hand…the benefit of bringing another antibiotic in the same class is, I think, that you have a pretty good sense of where the risk is and how to manage it.

So there's pluses and minuses to both. I think from our perspective, we are hungry to look at those innovative approaches that are differentiated from what's been done before, for all the advantages, recognizing that there are some unknowns and some things you need to be careful about. I would love for some of them to be that.

So there's pluses and minuses to both. I think from our perspective, we are hungry to look at those innovative approaches that are differentiated from what's been done before, for all the advantages, recognizing that there are some unknowns and some things you need to be careful about. I would love for some of them to be that.

At the same time…if we look at the classes of molecules and how they've been used, we've gotten huge benefit from second- and third-generation molecules in classes that are appreciated and understood. And now we've gotten close to 100 years of utility. So there's value in both. We're not saying we will only look at purely innovative things [new target, new chemical class], nor are we going to only look at those things that have been done three times before.

I think where we start is clinical need [and] patient benefit. What do we really need to bring to physicians to arm them and to drive patient benefit? Where is that need? Then we work our way backwards. And if that's a new modality that addresses it, fantastic. If it's an old modality that addresses it…that's where we should prioritize it. You know, if you gave me a magic wand, I'd probably pick a new modality most of the time. But we're living in the world of what exists.

We want to save lives. We want to treat the intractable infections that we can't otherwise treat and do it better, do it safer. And that's our focus.

CIDRAP News: The AMR Action Fund was launched by a coalition of leading pharmaceutical companies. Aside from the funding they are contributing, what additional roles will these companies be playing going forward in the selection process? Will they be involved in selecting drug candidates or in providing kind of technical knowledge?

Skinner: The short answer is no. The fund is operating and is set up independent from those pharmaceutical companies that that are supporting us financially as limited partners. Wellcome Trust is also a key contributor financially and otherwise. The founding of the fund also involved the World Health Organization [WHO].

I would say one of the things I hope they do in the future is acquire our portfolio companies. And if we can finance compelling anti-infectives, and some things around reimbursement change and things like PASTEUR [The Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance Act] move forward, hopefully they can use their worldwide muscle to bring these new antibiotics to patients where they're desperately needed.

So I hope in the long run that they are acquirers and natural homes for these products after they're approved. But they're not part of the decision process. The decision process is all internal to the fund.

CIDRAP News: Will the selected candidates be required to have stewardship and access plans for their products?

Skinner: They will. But I think we have to remember that these are companies that have been grossly undercapitalized for the last decade or two. So, in fairness to a company that is scratching to run their phase 3 [trial] and not go bankrupt and to bring their molecule to approval, the thought of trying to get them to launch in 147 countries is just not really fair.

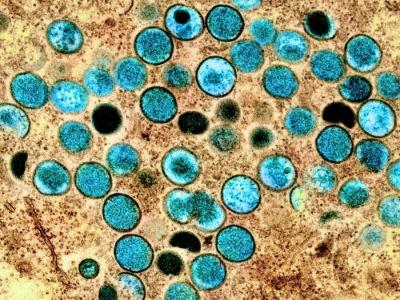

At the same time, I do think we need some pathways there, because my goal is to bring these drugs to patients who need them where they need them. We know how small the world is with COVID now. AMR is no different, right? Resistance rising in one part of the world is inevitably going to get to everyplace else. And we've seen that with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter, E Coli, NDM-1, et cetera. Not as fast as COVID, but these things spread, and if we really think about trying to keep our armamentarium of antibiotics vibrant, we need to think about this problem as a global problem.

So access is an issue. Stewardship is an issue. So is having antibiotics available without prescription, counterfeit antibiotics, adulterated antibiotics, antibiotics that that have lost activity because they're too old…we can go on and on. All drive resistance, and resistance only goes up. And some of these places don't have the diagnostics to be able to drive good stewardship, either. So there's a lot that has to come together globally.

I'd say probably the most similar parallel is around global warming. This is a global problem. No one country can solve it. It really needs to be solved across the spectrum, from the G7 to the G20 to WHO and everything in between. It is a huge problem…and hopefully we continue to make progress there on multiple fronts.

CIDRAP News: I want to talk a little bit about sustainability. Obviously, there's a larger goal here beyond two to four new antibiotics by 2030. Given the nature of antibiotic resistance, you want a sustainable pipeline to keep pumping out new products. Can you lay out the different elements that you think will be necessary for building that sustainability?

Skinner: It's holistic. The more things we can put in place with appropriate stewardship, [and] bringing the right antibiotic to each patient's infection… gives us more breathing room. This is not so simple as "all we need is more investment in antibiotics." It's a complex problem. We need to address each piece of that stool—access, stewardship, and innovation—to optimize the solution.

We've certainly seen over the past few decades a dearth of new approaches that have panned out and the number that we need. So we need to drive that innovation. I think the overall ecosystem needs to function. It's functioned phenomenally well in the past, but it's been broken over the past couple of decades.

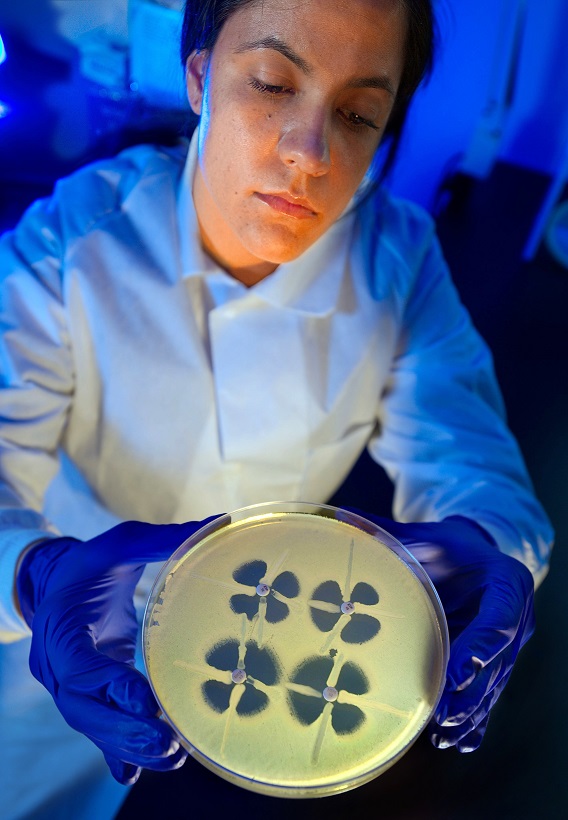

We need good basic science investment. [We need] academic [researchers] really understanding the target space and pioneering innovation for new modalities and the like. We need investment in translating that academic work into product candidates.

Thank goodness for groups like CARB-X and the Repair Impact Fund, who are trying to drive the best of that innovation. I think they've gotten pretty darn good output for what they've been able to put to work, and hopefully there will be additional resources brought to bear there.

We also need an ecosystem where capital flows into that work…in a natural way that brings not only capital but also really smart minds to help build companies. You know, drug discovery and development is a tough space when everything lines up. We're taking a lot of known and unknown risks, and we need that vibrant ecosystem to deliver innovation as it has in every other therapeutic area over the last 20 or 30 years.

We [also] need scientists in this space. I'll tell you one thing, I have a big concern over the next decade or so if we don't fix this problem. A lot of the scientists I've worked with in this space…we're getting gray hair. A number of them have retired. If we keep starving this field of resources…if I'm a brilliant chemist and I want to go into pharmaceuticals and make a difference with my work and really bring some transformative medicines to patients, am I going to go into a new cancer company, or am I going to go into an anti-infective company that might be bankrupt in a year? We need young people coming in, and we need to train them and pass on our knowledge.

I worry that if we continue to starve this field for 10 years, we're just losing capability. If we don't keep the human talent and the scientists and the entrepreneurs doing as much good as they do in other fields in this field…we're going to be in a very poor position to solve these problems going forward.

CIDRAP News: There is a widely recognized need for market-based policy reforms to support antibiotic development. The PASTEUR Act is one such reform. The United Kingdom has launched a pilot subscription model for antibiotics through the National Health Service. How important is that Congress pass the PASTEUR Act, or something like it?

Skinner: I think it's hugely important. I think, whether it's the PASTEUR Act or something similar to it, something akin to what the UK has done, or something different, the market's broken.

To get new antibiotics made, we need to incent people to innovate and to drive forward that innovation and to take that entrepreneurial risk and to take the clinical risk and develop things that matter and have them available. And we want them available, frankly, before we have that massive need. I think John Rex's analogy to a fire extinguisher is right. Sooner or later lightning strikes and there's a fire. And we have fire departments not because we want fires, but because we know there are some risks of them and we want to make sure we're ready to put them out. And I think [antibiotics are] the same thing. It's infrastructure.

It's also the foundation of modern medicine. Without antibiotics, we are set back 100 years in where medicine is with chemotherapy, stem cell transplants, organ transplants…you name it. The average life expectancy compared to 100 years ago is phenomenal. And a big part of that is antibiotics. I've seen some studies that say antibiotics may have contributed to as much as 10 years of added life expectancy. I don't think anything else comes close. We need a market for them, right?

The value antibiotics bring is, to my mind, probably the greatest value of any pharmaceutical class from the standpoint of that benefit at a very modest cost. But the flip side of that, plus some other attributes in how the system works is, [is that with] a new antibiotic we want good stewardship. We don't want to use it as first-line therapy. We don't need to. But we sure need to use it where it's needed.

The value antibiotics bring is, to my mind, probably the greatest value of any pharmaceutical class from the standpoint of that benefit at a very modest cost. But the flip side of that, plus some other attributes in how the system works is, [is that with] a new antibiotic we want good stewardship. We don't want to use it as first-line therapy. We don't need to. But we sure need to use it where it's needed.

But if we have [that new antibiotic] before there's a huge crisis, the need is modest. And if you're paid on volume, which is the traditional approach for [how] our system works—not only for drugs but for everything else in society—you're not going to get paid much for that new, incredibly important antibiotic that is the only thing that's going to cure a particular infection.

But if you're the innovator, if you've just spent however much money you want to say it costs to develop an antibiotic, whether it's one or more, you also have to finance the failures. And we've seen it with Achaogen and Melinta. You go bankrupt just trying to keep the lights on and keep the drug available because of the way antibiotics are used. But that drug in 20 years is still going to be saving lives.

This is the challenge. The system's broken. You're going bankrupt developing a new antibiotic when you get it out, you can't bring in the money, but we desperately need them. We need those fire extinguishers. We need them for the handful of patients we have today, and we need them for the many multiples that will need them tomorrow.

So whether it's something like PASTEUR or something like the UK model, or any hypothetical solution which says, "Use the right antibiotic each and every time, don't use it when you shouldn't, use the best one for every patient, and let's reward the system for that value"…that's kind of where we need to go. And if we do that right, with the right incentives, the right amount of incentive—not too much, not too little, focused on meaningful new antibiotics—I think capital will flow then and people will take risks and the system will work. It's delivered huge value across healthcare.

Not every great idea works, and those that don't, you know, you weed them out and you fertilize the ones that have good prospects. But those products that are going to deliver value have to be rewarded, or nobody is going to do another one. And I think that's where we are. We need enough incentives to make the system work.