A study today in Open Forum Infectious Diseases has found that consultation with an infectious disease (ID) physician is associated with significant reductions in mortality in patients with certain multidrug-resistant (MDR) infections.

The single-center study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis found that 30-day mortality in patients with MDR Staphylococcus aureus was 52% percent lower when ID specialists were involved in care, and 59% lower in patients with MDR Enterobacteriaceae. ID consultation remained associated with reduced mortality in patients with these infections 1 year later.

While previous research has shown that ID consultation is associated with reductions in mortality, treatment failure, and readmission for patients with different types of infections, few studies have looked specifically at how ID specialists can affect outcomes for patients infected with invasive MDR organisms (MDROs). The lead author of the study says the findings reiterate the critical role of ID specialists in helping patients with these types of infections, especially at a time when antibiotic resistance—including with MDROs—is becoming an increasing problem in healthcare.

"If there was a drug that reduced heart-attack mortality by 50%, you can bet all the cardiac patients would be on it," Jason Burnham, MD, an infectious disease specialist and instructor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine, told CIDRAP News. "I think we provide a benefit that not everyone is aware of."

Reductions in mortality, readmission

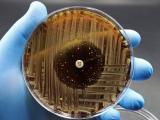

The retrospective cohort study, conducted at a 1,250-bed academic medical center in St. Louis from 2006 through 2015, analyzed hospitalized patients with MDR Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus spp., S aureus (including methicillin- and vancomycin-resistant S aureus), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or Acinetobacter spp. isolated from a sterile site, such as the bloodstream, or from a bronchoalveolar lavage/bronchial wash culture.

The primary end points were death and readmission after infection. The association of these end points with ID consultation was determined using Cox proportional hazards models, a statistical method for investigation the association between the survival time of patients and one or more variables.

Overall, 4,214 patients with MDRO were identified; 840 (19.9%) died or were discharged on hospice within 30 days of the first positive culture, and 1,832 (43.5%) died within 1 year. Among 2,371 patients without an ID consult, 578 (24.4%) died within 30 days of positive culture, and 1,115 (47.0%) died within a year; among the 1,843 patients who had ID consults, 262 (14.2%) died within 30 days, and 717 (38.9%) died within a year.

After multivariable adjustment, ID consultation was significantly associated with reductions in 30-day and 1-year all-cause mortality for MDR S aureus (hazard ratio [HR], 0.48 and 0.73, respectively) and MDR Enterobacteriaceae (HR, 0.41 and HR 0.74), as well as 30-day mortality risk in patients with several different MDR infections.

For MDR Enterococcus infections, ID consultation was marginally associated with reductions in all-cause mortality at 30 days (HR, 0.81). No association between ID consultation and reduced mortality was found for patients with Acinetobacter or Pseudomonas infections, the two smallest groups on the study.

ID consultation was also associated with reduced risk of 30-day readmission, but only for patients with MDR Enterobacteriaceae (HR, 0.74). Burnham said the lack of an association between ID consultation and readmission for other MDR pathogens could be due to small sample size or underlying medical conditions in the patients, such as diabetes or heart problems, that may have resulted in hospital readmission. "Sometimes it's hard to prevent a readmission," he said.

Since Burnham and his colleagues did not have access to drug administration data, they can't definitively attribute the reduced mortality to higher rates of appropriate antibiotic therapy. But Burnham speculates that understanding the right antibiotic therapy likely plays a role.

"Because we're trained in this, we know which antibiotics to give…so it seems quite logical that we'd be better equipped to choose the most appropriate therapy," he said. "Sometimes that doesn’t necessarily just mean knowing which antibiotic fits up with the susceptibility profile of the organism. It might mean the one that's best for their kidneys, or maybe they need two because they have a hard-to-control infection."

Breadth of expertise

As an ID specialist, Burnham isn't surprised by the results of the study. But he said that not everyone, including other physicians, is aware of the breadth of ID specialists' expertise. It's more, he explained, than simply understanding the appropriate drug-bug match.

Burnham brought up methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) as an example to illustrate his point. While MRSA in the bloodstream is a serious problem, he explained, the pathogen is also notorious for "hiding" on heart valves, in prosthetic joints, and in the spine. Because ID specialists know this, they might recommend spinal imaging studies or heart ultrasounds for patients who showing typical invasive MRSA symptoms like fever and chills but may not have the bacteria in their bloodstream—something that might not occur to non-specialists.

In addition, patients with MDROs frequently have to be put on intravenous antibiotics, which tend to be more toxic and require closer monitoring for appropriate levels and potential interactions.

Burnham said it's the deep understanding of these issues, from source control to drug toxicities, that makes ID specialists so valuable.

"It's a very complicated area, and because we do it all the time we're more comfortable with it, but not everyone necessarily is," he said. "If you needed brain surgery, you'd go see a brain surgeon, so if you have a bad infection, you want to see an infectious disease doctor."

Unfortunately, Burnham noted, there aren't enough ID physicians to see all the patients with bad infections. And interest in the field appears to be waning. A 2017 paper in Clinical Infectious Diseases noted that the number of trainees entering the specialty has plummeted since 2011, and that ID continues to have a substantially higher percentage of vacant positions than most other medical specialties.

"In an ideal world, we would increase the capacity of the infectious disease profession to see all these patients…but I'm not certain that's possible," Burnham said. One solution, he suggested, might be the development of an algorithm that can determine levels of ID complexity. That might enable hospitals to figure out patients who may not need an ID specialist but could be helped by an ID pharmacist.

"Maybe that would be a way to get infectious disease involvement for the patients who need it," he said.

See also:

Mar 15 Open Forum Infect Dis study