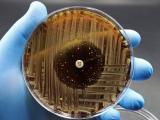

A new study shows that, despite having newer options for antibiotic-resistant infections, US clinicians are still frequently opting for less optimal older, generic antibiotics.

The study, which was conducted by researchers with the National Institutes of Health and published late last week in the Annals of Internal Medicine, found that, from 2019 to 2021, more than 40% of patients at US hospitals who had infections with difficult-to-treat resistance (DTR) were treated exclusively with traditional antibiotic agents, including antibiotics that were known to be potentially toxic, when newer options were available.

In addition, at more than a third of the hospitals, no patients received any of the next-generation antibiotics for gram-negative infections that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 2014.

The authors of the study say the findings could have significant implications for future antibiotic development and for policy makers who are focused on efforts to fix the broken market for antibiotics.

"There is an urgent need to understand why clinicians at hospitals with access to newer agents do not always prefer newer (over older) agents," they wrote.

Data show new antibiotics underused

Using a national database of patient encounters, the researchers focused on seven antibiotics targeting resistant gram-negative pathogens that were approved by the FDA from 2014 to 2019: ceftolozane-tazbactam, ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem-vaborbactam, plazomicin, eravacycline, imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam, and cefiderocol. To evaluate the use patterns of these antibiotics, the researchers first calculated the quarterly percentage change in antibiotic use from 2016 through June 2021, then examined the antibiotics used to treat patients infected with DTR pathogens.

"A pathogen is considered DTR if there are not any highly safe and effective first-line antibiotic options available to treat the patient; DTR adds clinical value by displaying prognostic utility and helping identify patients historically prescribed older 'reserve' agents but for whom clinicians might now preferentially prescribe available newer and safer antibiotics," the authors wrote.

The study also looked at factors associated with the use of new versus old antibiotics.

There is an urgent need to understand why clinicians at hospitals with access to newer agents do not always prefer newer (over older) agents.

At the 619 hospitals that reported data from January 2016 through June 2021, the use of the new antibiotics increased, with ceftolozane-tazobactam (approved in 2014) and ceftazidime-avibactam (2015) the most widely used; four of the other new drugs were used more sparingly, and eravacycline was not prescribed at all. Use of traditional agents like polymyxins, aminoglycosides, and tigecycline declined.

Almost 80% of older-antibiotic use deemed suboptimal

Of the 362,142 patient encounters that involved one or more positive cultures with a gram-negative organism at 299 hospitals from January 2019 to June 2021, 2,551 (0.7%) displayed DTR pathogens. The most common DTR pathogen was Pseudomonas aeruginosa (48.2%), followed by Acinetobacter baumannii (22%). Enterobacterales species collectively accounted for 23% of DTR pathogens.

Patients were treated with new antibiotics in 1,540 (58.8%) episodes involving DTR pathogens, and with traditional antibiotics in 1,091 (41.5%). Of the episodes in which a traditional antibiotic was used, 865 (79.3%) were treated with at least one agent with known suboptimal safety or efficacy.

Analysis of patient-level factors showed that patients with bacteremia and chronic diseases had a greater adjusted probability of receiving a new antibiotic, while analysis of hospital-level factors found that hospitals with antibiotic-susceptibility testing capacity had a higher probability of using new agents and smaller rural hospitals had a lower probability. At 107 (36%) of the 299 hospitals, no patients received any of the new antibiotics over the study period.

"In summary, despite the introduction of 7 new antibiotics against DTR gram-negative infections between 2014 and 2019, this armamentarium is not being fully used by clinicians even when they have access to these agents," the authors wrote.

Uncertainty about susceptibility, applicability

So why aren't the antibiotics that have been developed in response to the rise in multidrug-resistant infections being used more? The authors suggest several factors could be at play.

One is the price: the mean average daily wholesale price of the seven new antibiotics was $1,063.69, compared with $173.41 for the 11 traditional agents. Another is the imbalance between the new antibiotics and unmet pathogen targets. While all but one of the new antibiotics have activity against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, only two have activity against carbapenem-resistant A baumannii. That could explain why more than two thirds of patients with DTR A baumannii didn't receive new antibiotics.

An additional factor is access to susceptibility testing for the new antibiotics, which may have helped clinicians feel more confident about using the new drugs. On the other hand, if a hospital's antibiotic susceptibility panels covered only older drugs, clinicians at those hospitals might be more inclined to favor those options.

David Hyun, MD, director of the Antibiotic Resistance Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts, said this explanation rang true, based on his experience and observations he's heard from other clinicians.

"Clinicians will want some degree of reassurance," said Hyun, who was not involved in the study. "From a clinical standpoint, that level of uncertainty could compound your decision-making."

The authors also note that patients with highly resistant infections are poorly represented in clinical trials for new antibiotics and that "evidence underpinning the approval of next-generation gram-negative agents does not always represent the evidence that clinicians seek when choosing the optimal antibiotic to target highly resistant pathogens."

In an accompanying editorial, Jessica Howard-Anderson, MD, of Emory University School of Medicine, and Helen Boucher, MD, of Tufts University School of Medicine, highlight this point.

"Another important concern is that the patients in whom these drugs were studied are not the same as the patients with DTR pathogens who need these drugs," they wrote. "Clinicians are therefore left wondering whether these new antibiotics are applicable to their patients."

Hyun said this is another observation he's heard from clinicians.

"It becomes a little bit more difficult for clinicians to extrapolate a given drug that was studied for a very specific condition, for a very specific pathogen, and apply that to a patient that might have a different type of infection but the same type of bacteria," he said.

Howard-Anderson and Boucher add that expert guidance from groups like the Infectious Diseases Society of America, which published a guidance document on AMR in 2020, could help, along with innovative, pathogen-specific trials and access to rapid susceptibility testing.

An argument for pull incentives

Howard-Anderson and Boucher note that the study did have some notable limitations, including the fact that medical records weren't reviewed to determine the rationale for antibiotic therapy or to determine if the selected antibiotic was intended to treat the DTR pathogen.

Still, the authors say the findings reinforce the need for economic pull incentives that will keep drug makers invested in antibiotic development. The financial prospects for new antibiotics are already hampered by the fact that the number of patients with highly resistant infections is relatively small. If clinicians aren't always using the drugs when they have access to them, that could be another argument for financing mechanisms that delink antibiotic profits from sales.

Another important concern is that the patients in whom these drugs were studied are not the same as the patients with DTR pathogens who need these drugs.

Hyun says the underuse of new antibiotics is precisely why Pew and other infectious diseases groups have been advocating for pull incentives like the PASTEUR Act. The legislation, which was first introduced in Congress in 2020 but has yet to pass despite bipartisan support, would create a subscription-style payment model under which the federal government would pay companies up front in exchange for unlimited access to critically needed antibiotics for drug-resistant infections.

"The plain fact is that there's not a lot of consumption of these new antibiotics, and therefore there needs to be an economic support system," Hyun said.

The payment would be based on the public health value of the new antibiotics rather than sales volume. The authors of the paper say that whether it's a subscription-style payment model or another type of financial incentive, any future pull incentives must be patient-centered and should be tailored to ensure that new antibiotics truly target unmet needs.