Results from a randomized controlled trial of patients with bloodstream infections indicate that treatment with a 7-day course of antibiotics is non-inferior to a 14-day course, a finding that could have important implications for antibiotic stewardship.

The findings, published yesterday in Clinical Infectious Diseases, are significant because shortening antibiotic therapy is seen as an important tool for reducing unnecessary antibiotic use, and the potential hazards of excess antibiotic treatment, in hospitals. Several randomized clinical trials in recent years have found that shorter antibiotic treatments are as effective as longer treatments for a variety of bacterial infections.

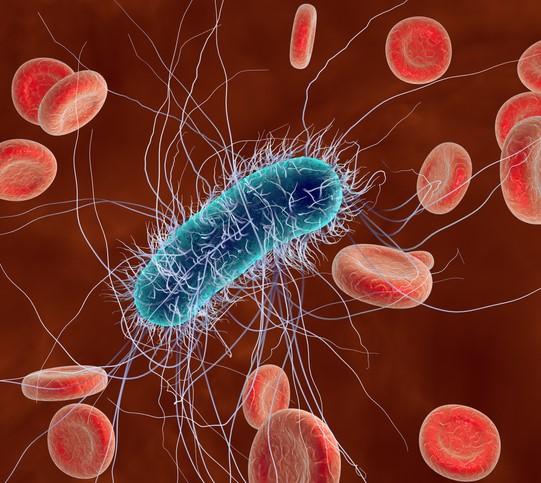

But patients with bloodstream infections, which are typically more severe and deadly than other bacterial infections, are rarely included in these studies. Current treatment guidelines recommend a range of treatment duration from 7 to 14 days for bacteremia, but the lack of data on appropriate antibiotic treatment for bloodstream infections means patients tend to receive prolonged treatment.

This study, led by a team of Israeli and Italian clinicians and researchers, is the first randomized clinical trial to explore whether a shorter course of antibiotics is appropriate for patients who have gram-negative bacteremia.

Study establishes non-inferiority

In the study, 604 adult patients hospitalized with gram-negative bacteremia at two academic health centers in Israel and one in Italy from January 2013 through August 2017 were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either 7 days or 14 days of antibiotic therapy. The study was limited to patients who had survived to day 7 and were hemodynamically stable and afebrile for at least 48 hours.

The primary outcome at 90 days from randomization was a composite of all-cause mortality, clinical failure, and readmission or extended hospitalization. Secondary outcomes included individual components of the primary outcome. The non-inferiority margin was 10%.

Among the 604 patients (306 in the intervention group, 298 in the control group), the main source of bacteremia was the urinary tract (411/604, 68%) and the main pathogens were Enterobacteriaceae (543/604, 89.9). The primary outcome occurred in 140 of 306 (45.8%) of the patients in the 7-day group versus 144 of 298 (48.3%) in the 14-day group, establishing non-inferiority (risk difference [RD], -2.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -10.5% to 5.3%).

In addition, no significant differences between study groups were demonstrated for any of the individual components of the primary outcome, including 90-day all-cause mortality. Thirty-six patients (11.8%) died in the short-duration group, compared with 32 (10.7%) in the long-duration group (RD, 1.0%; 95% CI -10.4% to 6.2%). Non-inferiority criteria were met in most of the study subgroups, except for those who received inappropriate empiric antibiotic therapy and those with bacteremia cause by a multidrug-resistant pathogen.

"In summary, among hospitalized patients with Gram-negative bacteremia, hemodynamically stable and afebrile for at least 48 hours without an ongoing focus of infection, 7 days of antibiotic therapy were non-inferior to 14 days," the authors of the study write.

The results also showed that duration of hospitalization and rates of super-infections were not significantly different between the two groups, and that there were fewer cumulative antibiotic days in the 7-day group.

At the same time, however, there was no significant difference in the development of antibiotic resistance or occurrence of adverse events—including Clostridium difficile infection—between the two groups. This is noteworthy because the primary arguments for shortened antibiotic therapy are the belief that it will reduce adverse events and the selection pressure for resistant bacteria.

Limitations of the study include the fact that the patients had a low severity of illness and that the vast majority of pathogens were Enterobacteriaceae. This suggests that the results may not be applicable to sicker patients or those with bacteremia caused by gram-positive pathogens or gram-negative non-fermenters such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Acinetobacter baumannii.

Results suggest 'paradigm shift'

In an accompanying commentary, Nick Daneman, MD, and Robert Fowler, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto write that shortening antibiotic treatment for bacteremia from 14 to 7 days would represent a major change in practice in North America. Recent surveys of Canadian intensive care and infectious diseases clinicians indicate that 14 days is the most common recommendation, and a multicenter study found that actual treatment durations were even longer, they note.

"The results of Dr. Yahav et al's study suggest that we are heading towards a paradigm shift in the recommended treatment durations for patients with bloodstream infection," they write.

Such a shift would also save money, they add, cutting drug costs by an estimated CAD $678 million to $798 million a year in North America. "If shorter treatment durations are associated with reductions in C. difficile infections and antimicrobial-resistant pathogens, the cost saving would be greater," they write.

Daneman and Fowler say they hope to extend the knowledge base on appropriate treatment for bloodstream infections through the Bacteremia Antibiotic Length Actually Needed for Clinical Effectiveness (BALANCE) trial, which will compare 7 versus 14 days of treatment for critically ill patients with bacteremia.

See also:

Dec 11 Clin Infect Dis abstract

Dec 11 Clin Infect Dis commentary