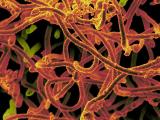

As Liberia over the weekend became the first of the hardest-hit countries to be declared Ebola free, an independent assessment panel released its initial review of the World Health Organization's (WHO's) role in the outbreak response, noting some early missteps and puzzling over other steps—or lack of them.

Meanwhile, experts met in Geneva today to map out the latest plans for developing drugs, vaccines, and other tools for battling the disease. And experts and pharmaceutical company representatives will meet tomorrow near Washington, DC, to discuss vaccine development and licensing.

Liberia declared Ebola free

In a May 9 statement, the WHO declared Liberia free of Ebola, as the country passed the 42-day mark since the last lab-confirmed case was buried. It said Liberia's interruption of Ebola transmission is a "monumental achievement," given that it reported the highest number of deaths in the biggest, longest, most complex outbreak since the virus emerged in 1976.

Forty-two days represent two incubation periods for the virus.

During the country's transmission peak last August and September, Liberia saw some of the outbreak's most tragic scenes, including overflowing treatment centers that were turning away patients and uncollected bodies that piled up on city streets, the WHO said. It added that although the country's capital, Monrovia, was hardest hit, all 15 of the country's counties reported cases, and health officials worried that Ebola might become endemic in Liberia.

The WHO praised the determination of Liberia's government and its people, the heroic work of local and international health teams, as well as international assistance that came in when case growth was exponential, in driving cases down to zero.

In a separate statement, the WHO singled out several other factors that helped Liberia become the first country to reach zero cases. Examples include decisive leadership by Liberian president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, early recognition of the importance of community engagement, strong support from the international community, and the deployment of self-sufficient foreign medical teams.

Liberia's last case involved a Monrovia-area woman who got sick on Mar 20 and died on Mar 27. Health officials monitored 332 people who may have been exposed to the patient, and none have developed symptoms and have been released from surveillance. The WHO said the country has maintained a high level of vigilance for new cases and that in April, its five dedicated Ebola labs tested about 300 samples a week, with all results negative.

Doctors without Borders (MSF) said in a statement that it welcomed Liberia's achievement, but it warned that with new cases still being reported in neighboring Guinea and Sierra Leone demonstrate that the outbreaks isn't over yet.

Mariateresa Cacciapuoti, who heads the MSF mission in Liberia, in a statement called Liberia's achievement a real milestone. "But we can't take our foot off the gas until all three countries record 42 days with no cases."

The group has said better cross-border collaboration is needed to prevent the disease from sparking up in Liberia again. "The Liberian government and Liberian people have worked hard to help us achieve 42 days of zero Ebola cases, but that hard work could be undone in an instant," she said.

Independent review cites early missteps

Meanwhile, an independent expert panel tasked in early March with reviewing the WHO's response to the Ebola outbreak released its initial findings today, which will be used during deliberations next week at the World Health Assembly (WHA). In 2010 the WHO appointed a similar external committee to review its response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

The six-member Ebola panel, headed by Dame Barbara Stocking, has met twice in Geneva and will travel to Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone in the coming weeks, according to the report. Stocking is the former humanitarian response leader at Oxfam GB and is currently president of Murray Edwards College at the University of Cambridge.

In its initial findings, the group said though a careful analysis of the WHO's Ebola response is needed, the focus should be broadened so that its recommendations can help the WHO respond to the next unexpected threat. It also emphasized that the assessment is a learning exercise to help advise on resources, systems, people, and changes in organizational culture needed to improve future performance.

Among the group's 12 main observations, it acknowledged that several public health and humanitarian crises were competing for WHO and United Nations (UN) attention when the Ebola outbreak emerged in West Africa. The panel also said that the event was particularly challenging because of fragile health systems, mistrust among communities, highly mobile populations, and transmission of the virus in urban settings.

The panel said, however, that a serious gap early in the outbreak was failure to fully engage local communities. For example, it said responders didn't prioritize the need for culturally sensitive messages that addressed cultural practices, such as traditional burials, that were fueling transmission and that bleak messaging failed at engaging communities.

"Medical anthropologists should have been better utilized to develop this messaging," they wrote, adding that the lapse was surprising, given the WHO's extensive experience with outbreaks.

Still unclear is why the WHO and its partners didn't mount an effective response, despite early warning from May through July, with the WHO calling it "unprecedented" as early as April. It added that affected countries, other WHO member countries, and the wider global community were also "behind the curve" in responding to the outbreak. The group said it is still probing the political, cultural, organizational, and financial factors that led to the delay.

The International Health Regulations faces issued with timely information sharing, clearance needed at several levels, and anxiety over potential consequences of declaring a public health emergency. Reviewers noted that the worries were somewhat justified, based on the flurry of border closures and flight restrictions that came in the wake of the emergency declaration, all steps that interfered with the response.

The outbreak revealed a gray area in how public health emergencies fit into a wider humanitarian system and at what point an outbreak becomes a humanitarian crisis that warrants a broader UN response, the team wrote. They said one way the two events differ is the uncertainty if assessing the likely spread of disease in a public health crisis. "It is important to consider how these systems should interrelate; the panel will revisit this matter in its final report."

Reviewers puzzled over the WHO's difficulty in communicating as the authoritative body in the outbreak. The committee noted that, despite the emergency media team it put in place, the WHO wasn't able to counteract sharp criticism of its work, which was made worse by the delayed emergency declaration, misleading Twitter messages, and leaked documents.

Experts echoed other observations that the WHO doesn't have a robust emergency operations capacity or culture and that there are signs that the WHO has struggled with reaching out to partners within the UN, in the private sector, and from nongovernmental groups.

The review panel made 20 recommendations that take aim at organizational culture, system changes, IHRs, financing, and workforce. It pointed out that country failures in investing in global public health are mirrored as WHO weaknesses and that it suffers when countries don't have the political and financial will to address global health threats.

Rather than establish a new agency for addressing health emergencies or appointing another agency to lead them, the panel said that better investments in the WHO to improve its operational capacity for emergency response would be a better use of resources. It urged the WHA to select that strategy so that reforms proposed earlier this year by the WHO's executive board—especially the global health emergency work force and the contingency fund—can be implemented quickly.

R&D experts meet in Geneva

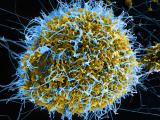

Also unprecedented in West Africa's Ebola outbreak was a rush to develop vaccines, drugs, and diagnostic tools. On that score, an expert group convened in Geneva today for a 2-day meeting to discuss lessons learned during the Ebola response and to form a roadmap for easing that process when faced with future disease threats.

In its background materials about the summit, the WHO said that, as with many tropical diseases, tools to prevent, treat, and diagnose Ebola didn't exist. It added, however, that 9 months after the outbreak began, there were three rapid tests, and a number of drugs and vaccines were in clinical trials.

The agency said the experience shows that the traditional research and development (R&D) model can be adapted and speeded up and that the summit's goal is to develop an emergency plan that establishes clear rules and guidelines to arm responders with safe and effective technologies.

At the opening session today, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan, MD, MPH, said, "Many serious diseases have no vaccines or therapeutic options, and some of these diseases have epidemic potential. The job now is to harness lessons from Ebola to create a new R&D framework that can be used for any new epidemic-prone disease."

VRBPAC meets tomorrow

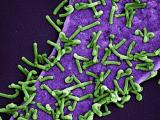

In a related development, advisors to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will meet in Silver Spring, Md., tomorrow to discuss the development and licensure of Ebola vaccines.

The meeting of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) will be webcast, and topics include regulatory considerations, Ebola epidemiology, effectiveness markers, postmarketing study considerations, animal study findings, human trial findings, comments from manufacturers, comments from the public, and discussion and possible recommendations.

Two vaccines are in phase 3 clinical trials in the outbreak region, with a few others in early human trials. However, declining numbers of cases in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone are making it difficult to show efficacy for both vaccines and treatments that have been developed to help fight the disease.

See also:

May 9 WHO statement on Liberia's Ebola-free status

May 8 MSF statement on Liberia

May 8 WHO interim Ebola assessment report

WHO background on Ebola R&D summit

May 11 Margaret Chan remarks at R&D summit

VRBPAC meeting materials