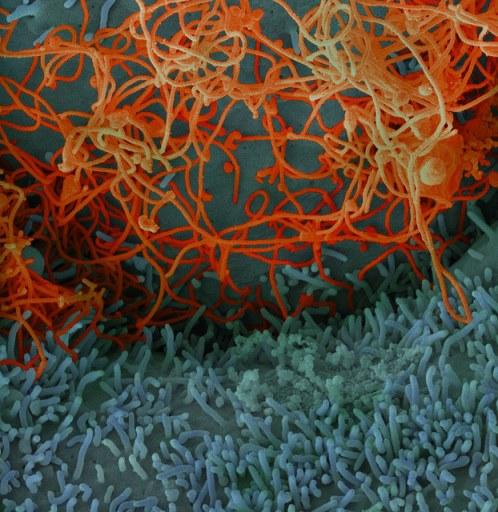

In a development that may add a piece of the puzzle about why West Africa's Ebola outbreak was so much worse than others involving the virus, researchers yesterday described mutations that made it more capable of infecting humans.

Adding weight to the findings, two different groups reported similar discoveries involving the same mutation—A82V in the gene that encodes the Ebola virus glycoprotein—in the same issue of the journal Cell. One group was led by primarily by US researchers based at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Harvard's Broad Institute, with the other a large international team that includes scientists from the University of Nottingham and the Pasteur Institute.

As the scope of the 2014-16 outbreak overwhelmed global health systems, experts worried that each new infection was adding more throws of the genetic dice, which could lead to changes enabling the virus to spread more quickly. By the time the outbreak wound down, more than 28,000 people were infected, including 11,000 people who died.

Jeremy Luban, MD, coauthor of the US-based study and professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, said in a Cell Press media release that Ebola is thought to circulate in an unknown reservoir, with rare spillovers to people. "When the virus does cross over, the effect has been devastating to those people who are infected. Until recently, the human disease outbreaks have been short lived, and the virus has had little opportunity to adapt genetically to the human host."

Enhanced infection in human cells

First, the researchers examined publicly available Ebola genetic sequences to look for mutations. They found that the A82V mutation arose early in the outbreak, in early 2014 as the virus moved from Guinea to Sierra Leone. They then used noninfectious virus material containing the A82V mutation to see how it infected different cells, the international-based group focusing in human and bat cells, while the US investigators did their experiments on cells from humans, non-human primates, and other mammal species.

Both teams found that the mutation enhanced the virus's ability to infect cells only from humans and other primates, which they said suggests that the increased infectivity they saw in human cells could have helped fuel the spread of the virus.

Comparing the findings with how the outbreak unfolded, the US team found that the A82V mutation was associated with a modest increase in mortality.

Meanwhile, the international team looked for signs of adaptation in Ebola's transition from bats, the presumed reservoir, to humans. They found other mutations and changes linked to A82V, along with hints that fruit bats, and not other species, are the likely Ebola reservoir.

Jonathan Ball, PhD, coauthor of the international group's study and professor of virology at the University of Nottingham, said in the Cell Press release, "We found that as Ebola virus was spreading from human to human, it apparently didn't have to worry about maintaining its infectivity in bats."

Findings may have 'caught the virus in the act'

In a commentary in the same issue of Cell, two experts wrote that the studies provide the clearest example so far of Ebola's functional adaptation to human hosts. The authors are Trevor Bedford, PhD, and Harmit Malik, PhD, both with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

"It would appear that both studies have the 'smoking gun' evidence to make the case for molecular adaptation in Ebola leading to increased human virulence," they wrote, adding that "herculean efforts" to sample and sequence the virus during the outbreak make the new findings an example of "catching the virus in the act."

They point out, however, that it's difficult to connect a single molecular change to the observed transmission patterns. Bedford and Malik also said the results beg the question of why the new mutation was more successful in its human host.

Next study steps

The researchers said they will continue their work to identify how the mutations made Ebola more infectious for humans.

Luban said, "It's important to understand how these viruses evolve during outbreaks. By doing so, we will be better prepared should these viruses spill over to humans in the future."

In the study from Luban's group, the researchers said the findings warrant follow-up with in vivo studies in high-containment (biosafety level 4) labs and cell-culture studies to compare different live Ebola variants.

See also:

Nov 3 Cell abstract for US-based study

Nov 3 Cell abstract for international study

Nov 3 Cell commentary

Nov 3 Cell Press news release