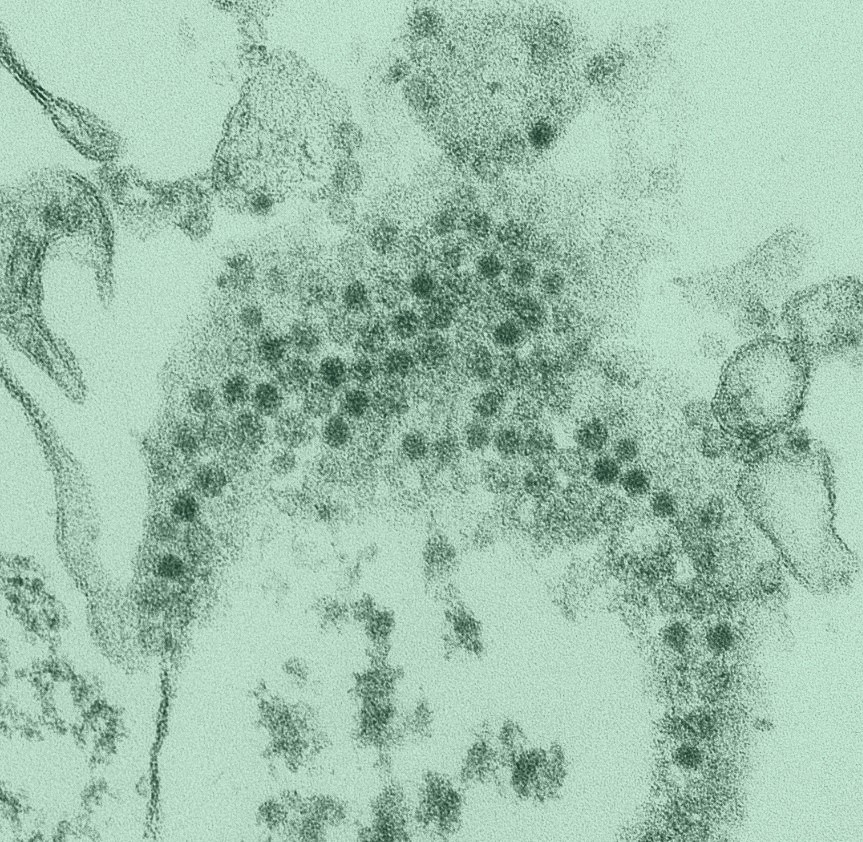

Transmission of enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), a respiratory RNA virus first identified in California in 1962, appears to have started accelerating before 2011, which could partly explain a more recent upswing in cases and outbreaks of related diseases around the world, suggests a study published in eLife.

Imperial College London researchers led the study, which estimated the prevalence of EV-D68 neutralizing antibodies using mathematical models and serum samples collected in 2006, 2011, and 2017 in England.

Implicated in acute flaccid myelitis

EV-D68 most often causes asymptomatic or mild respiratory diseases but has been implicated since 2014 in outbreaks of

acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), an uncommon but serious polio-like illness causing arm or leg weakness, mainly in children.

There is no treatment or vaccine for EV-D68, which typically circulates in the late summer and fall. It is difficult to determine the true incidence of infection or identify any changes in viral circulation because most countries conduct only passive disease surveillance, the researchers said.

While the virus was once limited to isolated cases or small case clusters, it has now been linked to wider outbreaks, starting with nearly 1,400 cases in 49 states and Washington, DC, reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2014. The study authors said the virus may have evolved to replicate more readily or developed mutations linked to immune escape.

"Another [hypothesis] is that the virus has become more pathogenic, and, as a consequence, the number of symptomatic (and therefore, reported) infections has increased independently of its transmissibility (i.e. the virus already circulated in the past but went mostly undetected)," they wrote.

Annual odds of infection climbed 50% over 10 years

Coinciding with the 2009 emergence of a new clade, or branch with a common ancestral strain, the annual odds of EV-D68 infection rose about 50% over the 10-year study period, mostly driven by a rise in the number of infections in children aged 1 to 5 years. Each year, the prevalence of viral antibodies in the serum declined in the 0- and 1- to 4-year age-groups, rose steeply up to age 20 to 29, and then leveled off.

"As for many other viruses, higher values in the 0-yo age class are likely the result of the presence of transplacentally acquired maternal antibodies that subsequently decline," the researchers wrote.

The increase in the rate at which people were infected from 2006 to 2017 led to a rise in the number of infections in the youngest age-groups over time and a decline in the oldest, with an inflection point at roughly 4 to 6 years. This then resulted in a decrease in average age at infection from 8.5 years in 2007 to 4.2 in 2017, for a 1:16 antibody-dilution cut-off, and from 14.3 years to 9.8, for a 1:64 cutoff.

"Despite such increase in transmission, seroprevalence data suggest that the virus was already widely circulating before the AFM outbreaks and the increase of infections by age cannot explain the observed number of AFM cases," the study authors wrote.

"Therefore, the acquisition of or an increase in neuropathogenicity would be additionally required to explain the emergence of outbreaks of AFM," they added. "Our results provide evidence that changes in enterovirus phenotypes cause major changes in disease epidemiology."

A CDC subject matter expert told CIDRAP News that high rates of mutation aren't uncommon for enteroviruses. "It is not clear that mutation rates alone account for any changes in the ability of the virus to cause disease," the source said. "Any single study cannot be used to conclude that a mutation in the virus led to a change in either EV-D68 prevalence or capability to cause any specific disease."

Not the only enterovirus tied to increasing outbreaks

Lead author Margarita Pons-Salort, PhD, of Imperial College London, told CIDRAP News that the findings align with those from previous studies in the Netherlands and the United States, which found that the prevalence of EV-D68 antibodies by age rose after 2014.

Our results provide evidence that changes in enterovirus phenotypes cause major changes in disease epidemiology.

"We don’t know how often viruses evolve in this way," she said. "It is intriguing though that a virus such as Enterovirus D68, that was first isolated several decades ago and that only caused very small outbreaks for many, many years, is now suddenly causing these bigger outbreaks of respiratory diseases."

EV-D68 isn't the only enterovirus that has recently begun to cause disease outbreaks, Pons-Salort said. "For example, Coxsackievirus A6, which is another enterovirus that causes hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) in children, has become the main cause of HFMD since the early 2010s, in some years and some places, replacing Enterovirus A71 as the main cause," she said. "The emergence of outbreaks of Coxsackievirus A6 worldwide is a phenomenon that we do not understand well yet either."

The symptoms of AFM include drooping eyelids or difficulty moving the eyes, facial droop or weakness, difficulty swallowing, slurred speech, loss of reflexes, and weakness or pain in the arms, legs, neck, or back.

"Although AFM is very uncommon, it is a neurologic condition that can have lifelong sequelae, and there is currently no treatment," Pons-Salort said. "Seeking medical care quickly if a child has symptoms of AFM is extremely important."

The authors called for research into the role of neutralizing antibodies among children younger than 5 years.

"In particular, it is unclear whether cross-reactivity with other enteroviruses contributes to these high seropositivity and general increase in antibody titres with age," they wrote.

The CDC said predicting EV-D68 prevalence or evolution isn't possible. "Despite attribution of the decrease in AFM and EV-D68 in 2020 to community effects of COVID-19 social distancing, we have observed an absence of a rebound in 2022," the source said.

People who are infected with EV-D68 but have no symptoms can still spread the virus to others. "This makes it difficult to prevent them from spreading as well," the CDC said. "The best way to help protect yourself and others is to wash your hands often with soap and water for 20 seconds, especially after using the toilet or changing diapers; avoid close contact with people who are sick; and clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces."