A nearly 20-year study of the forest food web at a Lyme disease hot spot in New York state found an important clue about what seems to drive the number of ticks that carry the disease: high numbers of rodents in settings where their predators, such as foxes, are low.

The study took place in Dutchess County, New York, an epicenter for Lyme disease. Over 19 years, researchers monitored six forested field plots on the grounds of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. To untangle the variables that influence tick populations, they monitored small mammals, blacklegged (deer) ticks, tick-borne pathogens, deer, acorns, and climate.

Also, the team tracked predator communities and tick infection rates at 126 sites throughout Dutchess County over 2 years. They published their findings in the July issue of Ecology.

Taal Levi, PhD, a lead author of the study and assistant professor at Oregon State University, said in a press release from the institute that the group's goal was to find patterns that could be used to protect public health. "By analyzing these long-term data holistically, we can tease out how changes in things like predator populations and food resources shift the community structure of the forest ecosystem, and ultimately the abundance of infected blacklegged ticks searching for a meal."

Small animals shoulder big tick burdens

As part of the study, each year from April to November the researchers have been trapping, tagging, observing tick burdens, and releasing small mammals, mostly mice and chipmunks, on six field plots on the Cary Institute grounds. They collected data from 19,299 mice and 3,755 chipmunks.

Richard Ostfeld, PhD, lead author and disease ecologist at the Cary Institute, said it wasn't uncommon to see mice with 50 feeding ticks attached. "They can carry huge tick burdens without having their fitness compromised. This is bad news for us, because these rodents are also very efficient at harboring and transferring pathogens to feeding ticks," he said.

Over the same period, the team dragged cloths over 450-meter sections of the plots to count thousands of ticks, nymphs, and larvae. They tested more than 7,000 for pathogens, including those that cause Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and babesiosis.

Acorn production harbinger

During the study period, the team set out seed baskets to monitor acorn production, and their analysis found that high acorn abundance during boom parts of oak tree cycles boosted rodent populations the following year and reliably pointed to an increase in infected nymphal ticks 2 years after acorn boom years.

Ostfeld said rodents that feed on abundant acorns are better able to survive the winter and reproduce, increasing their populations in the spring. "Questing larval ticks are more likely to feed on a white-footed mouse or chipmunk—animals that are very efficient at transmitting the bacterium that causes Lyme disease," he added.

Stalking the predators

To see if small mammalian predators influence tick infection rates, researchers placed camera traps at dozens of sites throughout Dutchess County in the summers of 2012 and 2013. Trap visitors included coyote, fox, bobcat, fisher, raccoon, and opossum. Then the investigators surveyed and tested ticks at the camera trap sites.

Locations with high predator diversity had lower infection prevalence of nymphal ticks than sites dominated by coyotes. Numbers of nymphal ticks were lowest where forest cover was higher, and bobcats, foxes, and opossums were associated with a reduction in tick infection.

Levi said coyote populations are expanding throughout the eastern United States and can reduce the number of predators that feed on small mammalian hosts of the Lyme bacteria. "This can result in larger small mammal populations, reduced turnover rates that allow infected individuals to live longer and infect more ticks, and changes to rodent behavior that make questing ticks more likely to feed on rodents, amplifying the infection rates of ticks," he said.

The weather factor

When the researchers looked at weather patterns from data recorded at the institute since 1984, they found that dry winter or spring weather was linked to a reduced density of infected tick nymphs.

Ostfeld said, "Ticks spend some 95% of their time away from hosts, on the ground. They are sensitive to drying out and need moisture to survive."

The right warning at the right time

Levi warned that the forested areas that are split up by development aren't able to support the type of predators that curb populations of small mammals that carry Lyme disease ticks.

And Ostfeld said fluctuations in acorn production, and drops in rodent populations that follow bust years, make it more likely that ticks would seek out other hosts, including humans, for blood meals.

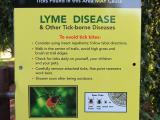

Tailoring public health messaging to the highest-risk times is critical for reducing disease levels in humans, Ostfeld said. "Issuing warnings based on these specific predictions, rather than broad-stroke PSAs [public service announcements], will hopefully counter 'warning fatigue' and encourage people to become more proactive in taking self-protection measures."

See also:

July Ecology abstract

Jul 9 Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies press release