The antiparasitic drug ivermectin reduced the incidence of malaria by 26% in a cluster randomized trial conducted in Kenya, which has a high rate of the disease and of use of bed nets against mosquito bites, according to a new study in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

"We are thrilled with these results," first author Carlos Chaccour, MD, PhD, said in a news release from the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), which led the study. "Ivermectin has shown great promise in reducing malaria transmission and could complement existing control measures."

Chaccour is a co-principal investigator of the BOHEMIA (Broad One Health Endectocide-based Malaria Intervention in Africa) project and was an ISGlobal researcher at the time of the study.

Ivermectin has shown great promise in reducing malaria transmission and could complement existing control measures.

Ivermectin is typically used to treat helminth-caused diseases like river blindness (onchocerciasis) and elephantiasis (lymphatic filariasis), but it was hailed as a COVID-19 treatment without sound data to support that premise. It is among the drugs being tested against malaria, because traditional mosquito-control methods, such as long-lasting insecticidal nets and indoor residual spraying, have become less effective owing to insecticide resistance and behavioral adaptations by mosquitoes.

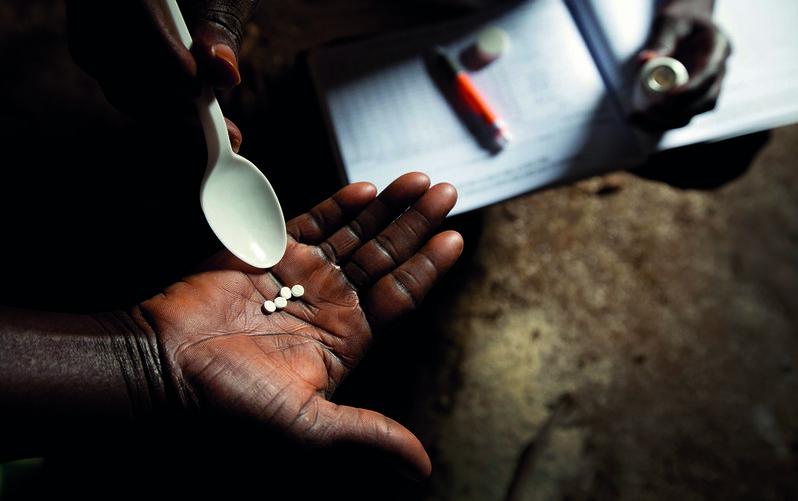

The drug has been shown to reduce malaria transmission by killing the mosquitoes that feed on people taking it. Almost 600,000 global malaria deaths were reported in 2023, among 263 million cases, according to the release.

Focus on protecting kids, teens

For the study, the research team randomly assigned 84 clusters of household areas in a 1:1 ratio to receive mass administration of ivermectin (400 micrograms per kilogram of body weight) or albendazole (another anti-helminth drug, 400 milligrams, for the control drug) once a month for 3 consecutive months at the beginning of Kenya's "short rains" season. They then tested the focus group—children 5 to 15 years old—for malaria infection monthly for 6 months after the first round of treatment.

The two primary outcomes were the cumulative incidence of malaria (assessed only among children 5 to 15 years of age) and of adverse events (assessed among all eligible participants). "We conducted a cluster-randomized trial in Kwale, a county in coastal Kenya in which malaria is highly endemic and coverage and use of insecticide-treated nets are high," the authors noted.

The 84 household clusters comprised 28,932 children and adults. Six months after the first round of treatment, the incidence of malaria was 2.20 per child-year at risk in the ivermectin group and 2.66 per child-year at risk in the albendazole group. The adjusted incidence rate ratio (ivermectin vs albendazole) was 0.74 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.58 to 0.95), for a 26% reduced risk. The rate of serious adverse events did not differ between the two groups.

The study authors wrote, "The results of our trial were consistent across multiple sensitivity analyses and showed a gradient effect, with higher protection observed among children living farther away from the cluster border and in clusters where the drug was distributed faster. Our trial showed a community-wide benefit with ivermectin, and the results are aligned with the WHO [World Health Organization]-proposed minimally required criterion of at least a 20% reduction in the incidence of infection that lasts for at least 1 month after the completion of a single round of treatment."

New approach in uncertain times

In the news release, senior author Regina Rabinovich, MD, MPH, director of ISGlobal's Malaria Elimination Initiative, said, "This research has the potential to shape the future of malaria prevention, particularly in endemic areas where existing tools are failing. With its novel mechanism of action and proven safety profile, ivermectin could offer a new approach."

In an accompanying NEJM editorial, US researcher Richard Steketee, MD, MPH, called the study "a well-conducted trial."

"These findings were not unexpected," he said, "but were the first to show that seasonal mass administration of ivermectin on a monthly schedule could be performed in alignment with other malaria or health interventions and provide a further substantial reduction in transmission."

"It is conceivable that doses could be given more frequently (a challenge for program delivery) or that a longer-acting endectocide could be identified through future research, thereby leading to a greater reduction in transmission that exceeds the observed 26%."

This research has the potential to shape the future of malaria prevention.

Steketee added, "Unfortunately, news of this encouraging intervention comes at a dire moment for global public health. Radical funding cuts in staff, commodities, program operations, and research have devastated existing malaria programs in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, as well as the many supporting organizations ... Until these resources are restored, continued deployment of currently effective interventions should be prioritized to prevent the undoing of progress and the likely resurgence of malaria."