A new study by researchers in the United Kingdom shows that a chlorine-based cleaner used on surfaces in UK hospitals is ineffective against Clostridioides difficile bacteria.

The study, conducted by researchers at the University of Plymouth and published in the journal Microbiology, examined the effect of clinical concentrations of sodium hypochlorite disinfectant (NaOCL) on C difficile spores, which can survive on hospital surfaces for months. C difficile is the leading cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea, and causes an estimated 29,000 deaths in the United States and 8,382 in Europe each year. While chlorine-releasing agents are used in the disinfection of fluid spills, blood, and feces in UK hospitals, recent studies have found signs of emerging sporicidal resistance.

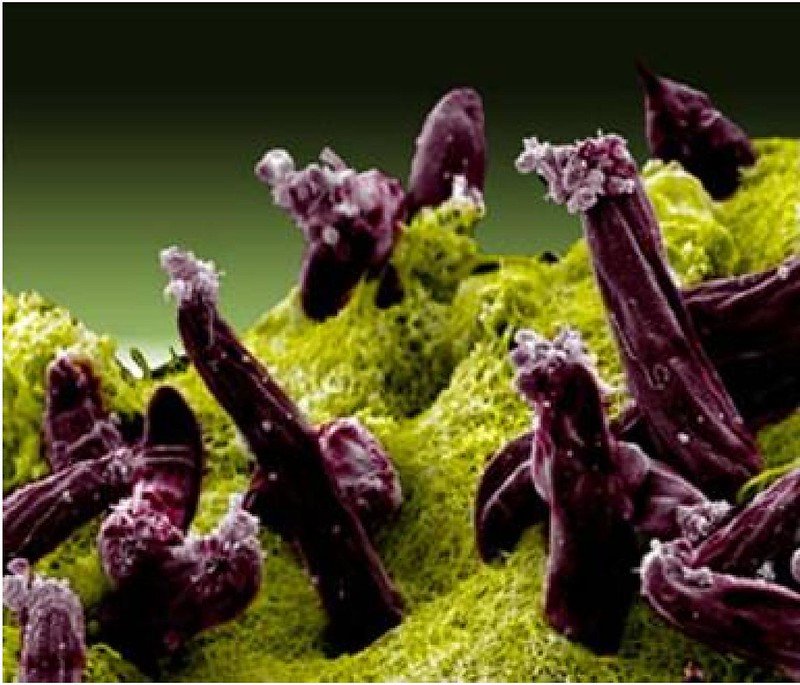

Three different strains of C difficile were exposed to NaOCL at concentrations of 1,000, 5,000, and 10,000 parts per million (PPM) for 10 minutes. Spore recovery was reduced for one of the strains, but examination of spores from all three strains showed no changes to the outer spore coat and no significant reduction in spore viability, indicating a tolerance to the disinfectant.

Scrubs, gowns could act as fomites

The researchers then applied spores from the three C difficile strains onto patient gowns and surgical scrubs and treated them with NaOCL. Although fewer spores were recovered from the fabrics than the liquid, the investigators still found that the scrubs and gowns retained the spores, and that the spores still survived treatment with NaOCL when it was applied directly to the fabric. This indicates that scrubs and gowns could serve as vectors of C difficile transmission in hospitals.

The study authors say the findings highlight an urgent need to review current C difficile disinfection guidelines.

"This study highlights the ability of C. diff spores to tolerate disinfection at in-use and recommended active chlorine concentrations," lead study author Tina Joshi, PhD, associate professor in molecular microbiology at the University of Plymouth, said in a university press release. "It shows we need disinfectants, and guidelines, that are fit for purpose and work in line with bacterial evolution, and the research should have significant impact on current disinfection protocols in the medical field globally."