A new study in the New England Journal of Medicine indicates that a form of tuberculosis that is resistant to at least four of the front-line antibiotics used to treat the bacterial disease is primarily spreading from person to person in South Africa.

The finding is significant, the authors of the study say, because it suggests that the long-held notion that extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) is acquired mainly as the result of inadequate treatment is only part of the story. It could help explain the dramatic rise of XDR-TB in South Africa, which has seen a 10-fold increase in cases since 2002.

And it's the type of evidence that's been needed, they say, to transform the approach to fighting spread of the disease.

Almost 70% person-to-person spread

In the study, researchers used a combination of methods to get a better understanding of how XDR-TB is being spread in the country. They started by interviewing and reviewing the medical records of 404 patients in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa who had been diagnosed as having XDR-TB from 2011 through 2014.

The province not only has nearly half the country's XDR-TB burden, the authors explain, but also its highest rates of TB and HIV. Overall, South Africa has one of the highest TB burdens in the world.

Participants were then asked to name contacts at home and work and other community settings (such as churches) and identify locations in the community where they spent two or more hours per week in order to create a picture of their social network.

In addition, the researchers performed genetic sequencing or "fingerprinting" of isolates from each patient to determine whether the various strains of XDR-TB matched.

What the researchers found was that 124 of the patients (31%) had previously been treated for multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB and met the clinical definition for acquired resistance, which develops through the selection pressure created by multiple episodes of ineffective treatment. But the other 69% of the patients had no history of treatment and appeared to have acquired XDR-TB through direct, person-to-person transmission.

"These patients had never previously had TB or been exposed to TB drugs," lead author Sarita Shah, MD, MPH, of the CDC's Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, told CIDRAP News.

That finding was supported by multiple genotyping methods, which showed that 84% of the patients had a strain of XDR-TB that genetically matched with at least one other person in the study. The matching strains formed 31 genotypic clusters that ranged from 2 to 14 participants, with 1 cluster sharing more than half the patients.

Finally, social network analysis showed that 30% of the patients had person-to-person or hospital-based epidemiologic links, an indication they had acquired XDR-TB through direct contact with another infected individual in the community or in a hospital. At least half of the epidemiologic links between patients occurred in households, but they also involved schoolmates and church members. And this wasn't just in one area, but across the entire province.

Shah said that the combination of the patient interviews, genetic sequencing, and epidemiologic information "created a complete picture of transmission as the primary cause in two thirds of the cases."

Shah and her colleagues say that while person-to-person transmission of XDR-TB isn't surprising, the extent of transmission occurring within the community is a concern, since methods to stop the spread of XDR-TB in the community are lacking. And the epidemic could be even wider. The social networks of the patients showed a large number of contacts (2,901) who were exposed to the disease and could be carrying it.

"There is potentially a large pool of people who were infected and could become sick," Shah said. Although she and her colleagues did not screen all of these contacts, other contact-tracing studies, she explained, have shown that nearly half the contacts of people who have drug-resistant TB will become infected.

Stopping the cycle of transmission

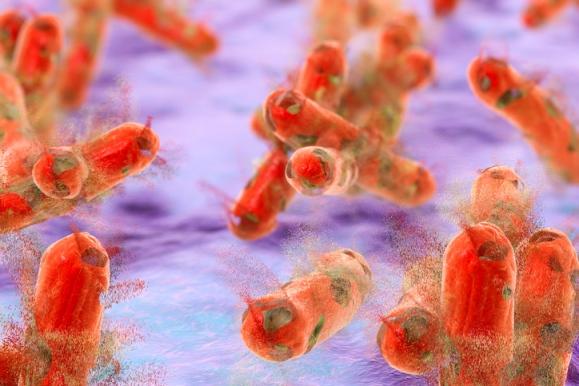

TB is a bacterial disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that most often affects the lungs. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), TB is one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide, causing 1.8 million deaths in 2015. Although curable and preventable, a 6- to 9-month treatment regimen consisting of four antibiotics—isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide—must be strictly followed. When patients don't follow and complete the regimen or receive inadequate care, the disease can become resistant.

The WHO says there are 480,000 cases of MDR-TB worldwide, and that information from countries with reliable data suggests that nearly 10% of those cases are XDR-TB. As of the end of 2015, 117 countries had reported at least one case of XDR-TB. The high degree of resistance in XDR-TB means that treatment options are limited. As a result, treatment is successful less than 40% of the time, and death rates are as high 80%.

Because TB can be spread through the air by coughing, sneezing, or even talking, public health officials have suspected that person-to-person transmission of drug-resistant TB is occurring. But they haven't had the data to support that belief. "This is something we suspected from the beginning, but we just didn't have the evidence to show it," Shah said.

This study, Shah said, provides "strong, incontrovertible" evidence that there needs to be more emphasis on halting transmission. That means better infection and prevention control in hospitals, screening for sick people in the community and separating them from the general population, and promptly initiating treatment.

"The real key here is to stop the cycle of transmission," Shah said. "We need to evaluate people who are in close contact, see if they have become infected or may be sick already, and get them into treatment early…to turn around this epidemic as quickly as possible."

See also:

Jan 19 N Eng J Med study