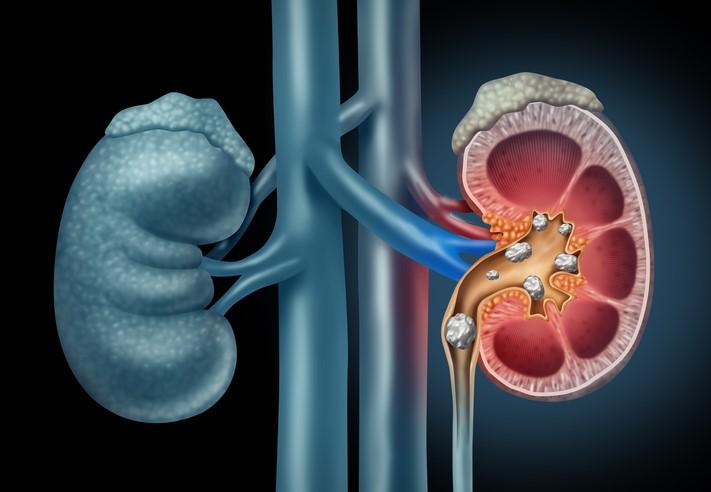

Over the last 30 years, the prevalence of kidney stone disease has risen by 70%, with the greatest increases seen in children and young women. Although dietary and lifestyle factors have been suggested as possible causes for this increase, the exact reasons remain unclear.

In a study today in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, researchers with Children's Hospital of Philadelphia suggest another possibility: oral antibiotic use.

The study found that exposure to five different classes of antibiotics 3 to 12 months before diagnosis was associated with increased odds of nephrolithiasis, and that the association was strongest among children. While the risk decreased over time, patients exposed to four of the five antibiotic classes remained at risk for kidney stones for up to 5 years after exposure.

"With these findings, I think it does suggest that antibiotic exposure, particularly if it's earlier in life, may be a risk factor for the development of kidney stone disease," lead study author Gregory Tasian, MD, MSCE, a pediatric urologist at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, told CIDRAP News.

A strong, consistent association

To investigate the link between oral antibiotic exposure and nephrolithiasis, the researchers conducted a population-based, nested case-control study using The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a database containing health records on more than 13 million adults and children who received care from a general practitioner in the United Kingdom from 1994 to 2015. The analysis included 25,981 patients with nephrolithiasis and 259,797 control subjects.

The primary exposure investigated was oral antibiotic exposure 3 to 12 months before the onset of symptoms, a period chosen because kidney stones form over weeks to months and antibiotics can affect the microbiome for several months after exposure. The most frequent indications for antibiotic use were chest infection, cough, upper respiratory tract infection, tonsillitis, and urinary tract infection (UTI). To determine whether there was an independent association between antibiotic use and kidney stone formation, the researchers adjusted for age, sex, and race, as well as other comorbidities, including UTI, and exposure to other medications.

The analysis found that oral sulfa antibiotics (odds ratio [OR] 2.33) cephalosporins (OR 1.88), fluoroquinolones (OR 1.67), nitrofurantoin (OR 1.7), and broad-spectrum penicillins (OR 1.27) were all associated with increased odds of nephrolithiasis among children and adults. No association was found with seven other antibiotic classes.

"With those five antibiotics, the association was remarkably strong and consistent, although the strength of the association varied by antibiotic class," Tasian said.

Further analysis revealed that the magnitude of the association was greater in children and adolescents and when exposure to the antibiotics occurred 3 to 6 months before diagnosis. In all classes except broad-spectrum penicillins, the associated risk remained statistically significant for 3 to 5 years after the antibiotic exposure.

For Tasian, the results provide an alternative explanation for the increase in kidney stone disease that he and one of his co-authors, pediatric nephrologist Michelle Denburg, MD, MSCE, have seen in their practices. The other explanations proposed for the increase, like changes in diet, "didn't capture the dramatic and rapid shift in the epidemiology of the disease." While diet hasn't changed much over the last 20 years, he explained, the prevalence of kidney stones in youth has doubled.

Tasian said the finding of higher risk among children and adolescents is consistent with the theory that age makes a difference when examining the health effects of exposure to environmental stressors or contaminants. It's also consistent with other research suggesting that antibiotic exposure early in development produces more profound alterations of intestinal microbiota. "Children and youth may be a particularly vulnerable population, where the effect of antibiotics may be greater than it is later in life," he said.

Antibiotics and microbiome disruption

Although Tasian and his colleagues did not investigate how antibiotics may be increasing the risk for kidney stone formation, they theorize that antibiotic disruption of the human microbiome is playing a role.

One theory, examined in previous studies, is that antibiotics may reduce the abundance of Oxalobacter formigenes, an intestinal bacterium believed to play a role in preventing kidney stones by reducing intestinal absorption of dietary oxalate, which combines with calcium to form kidney stones. These prior studies have found that patients with kidney stones also have lower overall diversity of gut bacteria. Since Oxalobacter is resistant to many of the antibiotics associated with increased risk of kidney stones in the study, that suggests those antibiotics could be affecting other gut bacteria or other metabolic functions involved in kidney stone formation.

Another possibility, Tasian and his colleagues suggest, is that antibiotics may select for multidrug-resistant bacteria in the urinary microbiome that promote kidney stone formation. They also acknowledge, however, that variables that they couldn't measure—such as diet, fluid loss due to underlying illness, and undiagnosed conditions—could be factors. They say more research on how antibiotics affect the microbiome and kidney stone formation is needed.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence that antibiotic use, particularly in early development, may have potential adverse health impacts beyond contributing to antibiotic resistance. For example, recent large epidemiological studies have found an association between antibiotic use and increased risk of diabetes up to 15 years after exposure. Other studies have linked antibiotic use in children with increased weight gain and allergy risk.

"Taken together, these studies of kidney stones and diabetes support the hypothesis that, by affecting the gut microbiome and its metabolic properties beyond just the intended effect of treating infections, health providers may be unintentionally contributing to chronic disease," Lama Nazzal, MD, and Martin Blaser, MD, of New York University School of Medicine write in an accompanying commentary. "Because the consequences may be delayed by months or even years, these outcomes could have slid under the radar of health practitioners."

Tasian said the findings could also bolster the case for more prudent use of antibiotics, especially in children, given that children under the age of 10 receive more antibiotics than any other age-group and that as much 30% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions are inappropriate. While providers and patients may understand that antibiotic stewardship can prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistance, he explained, the public health impact may not always be enough to discourage antibiotic use. But if antibiotic use is linked with a common disease, that could change the equation.

"When there's an association with a common disease, and one that's increasing, it just adds additional weight to the importance of judicious and appropriate use of antibiotics, and adds to the entire work being done in antibiotic stewardship," Tasian said.

See also:

May 10 J Am Soc Nephrol abstract

May 10 J Am Soc Nephrol commentary (subscription or payment required)