A report today from the United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment) highlights the environmental dimension of antimicrobial resistance.

The Frontiers Report, launched during the third UN Environment Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya, lists the release of antimicrobial compounds into the environment by households, hospitals, pharmaceutical factories, and farms as one of six emerging issues of environmental concern because of the potential impact on antibiotic resistance. The other issues are nanomaterials, marine protected areas, sand and dust storms, solar power, and human migration.

While the extent of environmental contamination from antimicrobial production and use by humans and food-producing animals remains unclear, several studies in recent years have documented the presence of antibiotics in agricultural soil, river and lake sediment, tidal estuaries, and wastewater facilities. The concern is that even low levels of antimicrobial residues in soil and water systems are contributing to the evolution of antimicrobial resistant bacteria.

"Around the world, discharge from municipal, agricultural, and industrial waste in the environment means it is common to find antibiotic concentrations in many rivers, sediments and soils," UN Environment Executive Director Erik Solheim writes in the foreword to the report. "It is steadily driving the evolution of resistant bacteria: a drug that once protected our health is now in danger of very quietly destroying it."

Several paths into the environment

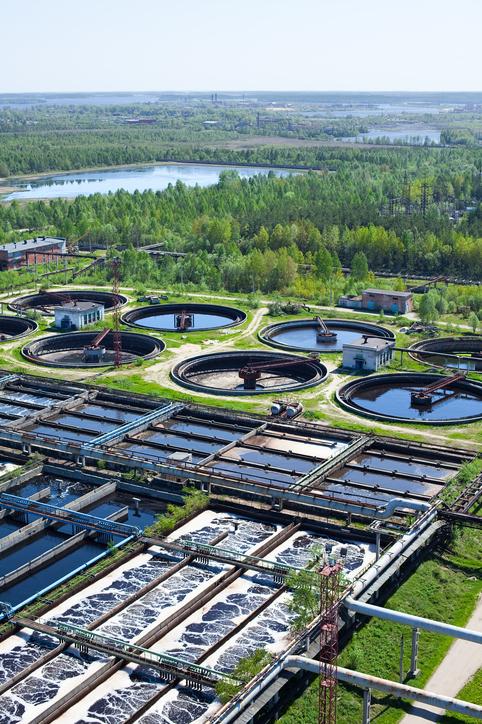

Antimicrobial residues can follow several paths into the environment. According to the report, up to 80% of antibiotics are excreted un-metabolized through urine and feces into sewage systems and flow into wastewater treatment plants that are also treating water from hospitals and industrial facilities. But because these treatment plants aren't designed to fully remove antibiotics and other pharmaceuticals from wastewater, the drugs end up being released into surface waters.

Antimicrobial use in agriculture also plays a role, as antibiotics used to treat food-producing animals are excreted through manure, which is spread onto fields as fertilizer and can be carried into nearby lakes, streams, and oceans with other untreated agricultural runoff. In addition, nearly three quarters of all antibiotics used in aquaculture may be lost to surrounding waters, according to the report.

Researchers have found antimicrobial residues in water and soil all over the world. A study in China earlier this year found five major antibiotic classes in estuary samples from coastal China, pinpointing wastewater streams from municipal sewage treatment and aquaculture as likely contributors. A recent study conducted in Minnesota found residue from 10 different antibiotics in lake bottom sediment dating back to the 1950s. All the lakes studied receive water from sewage treatment plants.

Pharmaceutical production facilities also contribute to the problem, especially in India, where a large proportion of antibiotics are produced. In April, a team of researchers sampled water from sources in and around Hyderabad, India—a major pharmaceutical manufacturing hub—and found high concentrations of three antibiotics and increased concentrations of eight others.

Once in the water and soil, the antimicrobial residues can interact with natural bacterial communities and with human and animal bacteria that have also been discharged into the environment. While the concentrations of antimicrobial residue found in surface water and soil aren't high enough to be lethal to their bacterial neighbors, laboratory studies have shown that even small amounts of antibiotics can exert some selective pressure for bacteria carrying antibiotic resistance genes to share those genes—not only with their offspring but also with other types of bacteria. Disinfectants and other industrial pollutants that end up in water, the report adds, may increase that pressure.

The studies in China and India suggest this may be what's happening in surface waters. In both studies, researchers also found a high abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in the water they sampled, indicating that the presence of antimicrobial residues in the water may be linked to the emergence of those resistance mechanisms. Other research has focused on wastewater treatment plants as potential "hot spots" for the horizontal transfer of resistance genes.

Mitigation strategies, stewardship may help

The question, the authors of the report say, is what level of antimicrobial residue will affect microbial communities. "Generating reliable temporal and spatial data on the exposure of microbial communities to antimicrobial residues in soil and water is vital to better understand the extent of selection that occurs in natural environments," they write.

Other unanswered questions are how much human exposure to resistant bacteria in the environment occurs through drinking water, food consumption, and direct contact with the environment, and what impact that exposure has on human health.

While noting that more research is needed on the issue, the authors of the report say developing strategies to reduce the amount of antibiotics and resistant bacteria in treated wastewater could help mitigate the problem. Some of the approaches that have been tried, with varying levels of effectiveness, include membrane filtration and ozonation to remove antibiotics and bacteria, ultraviolet light disinfection and heat treatment, and secondary and tertiary wastewater treatment facilities. They also suggest treating animal waste before applying it as fertilizer.

Antimicrobial stewardship will play a role as well, they add, by reducing the amount of antibiotics that get into wastewater in the first place.

See also:

Dec 5 Frontiers 2017 report

Dec 5 UN Environment news release