New US surveillance data indicate that infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens are moving beyond the healthcare setting.

In a study published last week in the American Journal of Infection Control, researchers with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and eight US public health departments reported that 1 in 10 infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) were community-associated, occurring in patients without the known healthcare risks—like hospitalization or stays in long-term care facilities—typically associated with CRE infections. Most were found in white women with urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Furthermore, molecular analysis of samples from those infections identified the presence of an enzyme that makes bacteria resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics and is carried on mobile genetic elements that are easily shared with other bacteria.

The findings are concerning because CRE infections are resistant to most antibiotics and are considered a major public health threat by the CDC. And while CRE are already a major target of hospital infection prevention and control efforts, the worry is that once they're established in the community and in a broader population, it will likely be more difficult to control them.

"CRE cause difficult-to-treat infections and have the potential to spread rapidly, including outside of the healthcare setting, where most cases currently occur…and some Enterobacterales are common causes of infection that occur in the community already," CDC epidemiologist and lead study author Sandra Bulens, MPH, told CIDRAP News. "So there's a real potential for these organisms to spread into the community."

CRE are spreading into a broader population

To get a baseline understanding of the incidence of community-associated CRE (CA-CRE) cases compared with healthcare-associated CRE (HCA-CRE) cases, and some of the associated risk factors, Bulens and her colleagues analyzed laboratory- and population-based surveillance data collected from eight sites in Georgia, Minnesota, Oregon, Colorado, New Mexico, Maryland, New York, and Tennessee from 2012 through 2015. The total population under surveillance in 2015 was approximately 15.2 million

The surveillance effort, which looks at bacterial isolates collected from clinical laboratories in the eight sites, is part of the Emerging Infections Program (EIP), a network of state and local health departments and academic institutions that work with the CDC to monitor incidence of CRE and other drug-resistant pathogens in inpatient and outpatient settings. According to a recent CDC report, there were 12,700 hospital-onset CRE infections in the United States in 2020, an increase of 35% from 2019. But this was the agency's first attempt at determining CA-CRE incidence.

Cases were defined as HCA-CRE if the culture was collected from patients who had been in an acute care hospital or long-term care facility for 3 or more days, or if it had come from patients who had undergone surgery in the prior year, were undergoing chronic dialysis, or had a urinary catheter or other indwelling device. If those factors were not present, cases were defined as CA-CRE.

A total of 1,499 CRE cases from 1,194 patients were included in the analysis, with 1,350 (90%) defined as HCA-CRE and 149 (10%) as CA-CRE. The overall crude incidence of CRE across all eight sites was 2.96 cases per 100,000 population. The sites with the highest crude incidence of HCA-CRE were Maryland and Georgia, while New York and New Mexico had the highest crude incidence of CA-CRE.

Bulens said the proportion of CRE in patients without identifiable risk factors, though small, was surprising.

"These are typically organisms identified in individuals with extensive healthcare exposure," she said. "Seeing this spread into the community is a concern because of the potential to cause infections that are challenging to treat in a broader population."

The organisms identified most frequently were Klebsiella pneumoniae (53% of cases) and Escherichia coli (18%), with K pneumoniae accounting for a higher proportion of HCA-CRE cases and E coli for a higher proportion of CA-CRE cases. Urine was the most common culture source, and the most common infections associated with CRE were UTIs, which accounted for 68% of all CRE cases, and were more common in CA-CRE than HCA-CRE cases (83% vs 67%).

Among the 1,194 patients, the 139 CA-CRE patients were similar in age to the 1,055 HCA-CRE patients (median age, 64 years), but were more likely to be female (84% vs 58%) and white (73% vs 51%). Bulens said the apparent racial differences between CA-CRE and HCA-CRE cases need to be further explored, as the numbers in the study were not large enough to be able to assess those differences.

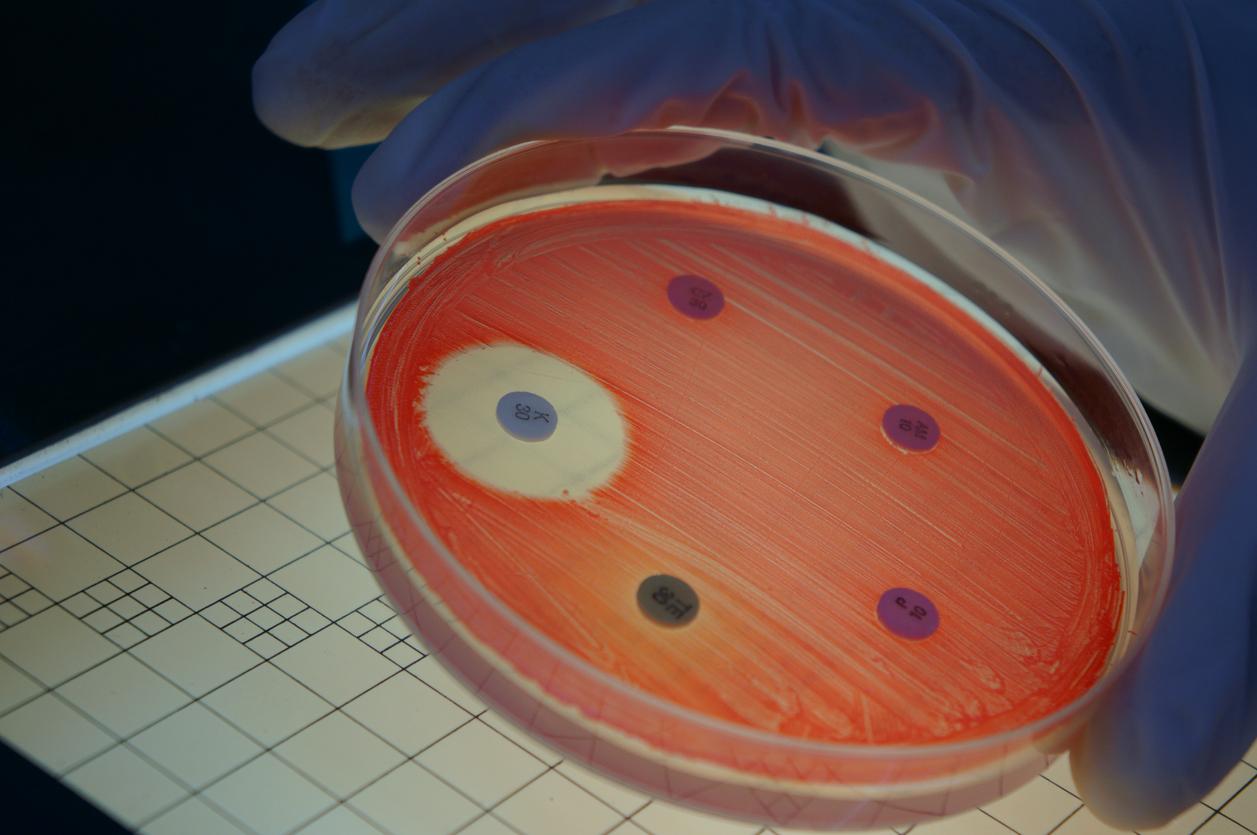

Whole genome sequencing of 12 CA-CRE isolates submitted to the CDC revealed that 5 harbored a carbapenemase gene, which carries an enzyme that can inactivate most, if not all, beta-lactam antibiotics and can be transmitted to other strains and species of bacteria. "This shows that we're not only finding CRE in the community, but we're finding the most concerning type," Bulens said.

Slowing community spread

"We know how rapidly these organisms can spread," said study co-author and CDC epidemiologist Maroya Walters, PhD, who noted the rapid community spread that's been observed in recent years in bacteria carrying another multidrug-resistance gene—extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)—that makes treatment more difficult. "What I really worry about is that CRE will follow the same pattern."

Walters said the next step will be to figure out what other factors might be associated with CA-CRE cases.

"Are these individuals who had recent antibiotic use? Are they caring for someone who's recently been in a hospital? All of that information will be really helpful for understanding more about these CA-CRE cases in the individuals at risk," she said.

Bulens said the findings highlight the importance of good infection prevention and control efforts "across the continuum of healthcare" to keep CRE infections out of the community. In a press release from the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), which publishes the journal, APIC President Linda Dickey, RN, MPH, said they also suggest that efforts to mitigate the spread of CRE will be needed beyond hospital walls.

"This study provides important initial data regarding the potential for CRE to become more common in the community," Dickey said. "It also reinforces the need for continued CRE monitoring outside of healthcare settings to inform community-prevention efforts and reduce the spread of serious, drug-resistant infections."