Research on long COVID in children is limited, and reported prevalences range widely, from less than 1% to 70%. And while it's a relatively new condition in an evolving field, experts say it could be better defined and measured through well-designed longitudinal studies that take children's unique presentations into account.

"I think it's largely because we're trying to apply adult framework to pediatric problems, and as a result, a lot of things are missed," David Putrino, PhD, director of rehabilitation innovation for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, told CIDRAP News.

"I think what we need are detailed longitudinal studies where we really take the time to characterize what long COVID looks like in a pediatric population," he said. "That has not been done. What has been done is 'let's treat them just like little adults,' which is always a pitfall in pediatrics."

No consensus on prevalence

In 2022, a systematic review of 22 studies involving children identified a long-COVID prevalence range of 1.6% to 70%, while a study from Germany from the same year that analyzed long-COVID among 157,000 COVID-19 patients suggested that kids were at the same relative risk as adults (30% vs 33%, respectively).

In July 2023, a systematic review of 31 studies published in 2022 involving 15,000 children concluded that 16% of children had persistent symptoms 3 months after infection. Another systematic review from that period found that 1.3% of US children ever had long COVID and that 0.5% currently had it in 2022.

Different symptoms, limited vocabulary

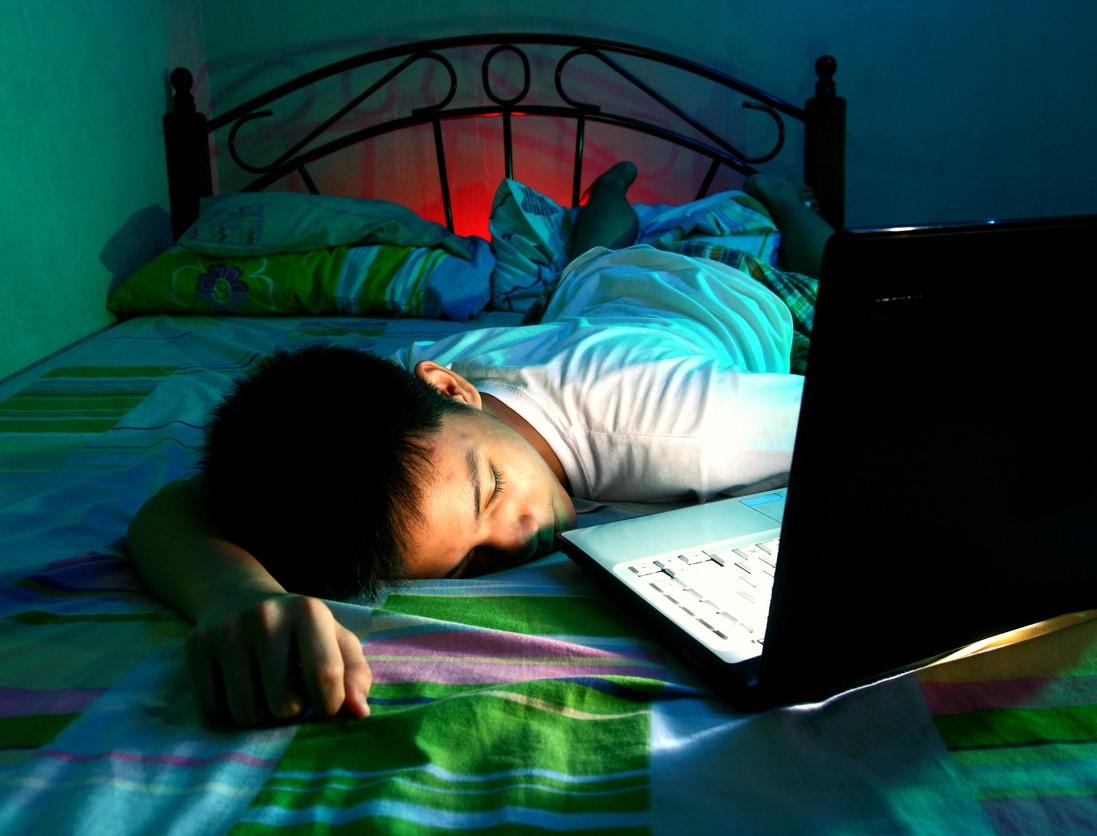

Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis and chief of research at the VA St. Louis Health Care System, told CIDRAP News that many children likely aren't diagnosed as having long COVID because they don't recognize or have the vocabulary to report their symptoms.

"Kids don't come home and say, 'Mom, I have postexertional malaise, I have brain fog,'" he said. "What happens is that they start doing poorly in school, and parents find out weeks and weeks later."

Hannah Davis, cofounder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, a group of long-COVID patients who are also researchers, said recognition can be particularly difficult in younger, preverbal children.

"Generally, long COVID research in children has been lacking compared with long COVID research in adults," she said. "A very sad thing to me is that I, and the other folks with long COVID as adults, we had this whole life where we understood what it meant to be healthy and active and not have these symptoms, and children don't necessarily, so you see it manifest in different forms."