Editor's note: Today's commentary was submitted to CIDRAP by the authors, who are internationally renowned experts on risk communication and crisis communication. Peter M. Sandman, PhD, originated the "Risk = Hazard + Outrage" formula for risk communication. In addition to his work on risk controversies, he speaks, writes, and consults widely on communication aspects of pandemic preparedness and other public health threats. Jody Lanard, MD, a psychiatrist by training, is also a risk communication speaker, writer, and consultant. She specializes in public health crisis communication, especially in developing countries. Much of their risk communication writing is available without charge on the Peter M. Sandman Risk Communication Website (www.psandman.com/). Commentaries submitted to CIDRAP do not necessarily represent the center's scientific position.

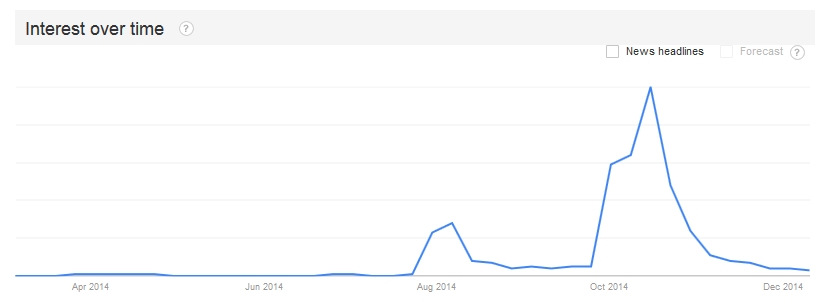

In contrast to the Ebola crisis in West Africa, which started in late 2013 and will last well into 2015 or longer, the US "Ebola crisis" was encapsulated in a single month, October 2014. But there may well be US Ebola cases to come, brought here by travelers or returning volunteers. And other emerging infectious diseases will surely reach the United States in the months and years ahead.

So now is a propitious time to harvest some crisis communication lessons from the brief US Ebola "crisis."

We're putting "crisis" in quotation marks because there was never an Ebola public health crisis in the United States, nor was there a significant threat of one. But there was a crisis of confidence, a period of several weeks during which many Americans came to see the official response to domestic Ebola as insufficiently cautious, competent, and candid—and therefore felt compelled to implement or demand additional responses of their own devising.

To some extent this brief overreaction was inevitable, simply because a terrifyingly lethal infectious disease had made its way from fiction to reality, from small outbreaks to a major epidemic, and from Africa to America.

New risks typically provoke such a temporary overreaction, which we have labeled an "adjustment reaction." The strength of the US Ebola adjustment reaction, however, was exacerbated by a number of official crisis communication errors.

Four of the main errors are delineated below.

Early US response

But first, consider phase one of Ebola in the United States, from early August through late September 2014. During this phase, starting with the repatriation of Kent Brantly, MD, and ending with the diagnosis of Thomas Eric Duncan, the public generally accepted what public health professionals were telling them about Ebola. As a result, public health professionals generally found the public's reaction acceptable, and accusations that the public was overreacting, hysterical, or irrational were infrequent.

After the announcement that two infected American healthcare workers (Brantly, followed by Nancy Writebol) were to be repatriated in early August, there was immediate intense interest, and a vivid but small outcry against bringing Ebola-infected persons into the country.

But the general public lost interest fairly quickly, believing the repeated assurances that the two patients would not spread Ebola to others in the United States. Most laypeople got the impression then that public health officials and experts were trustworthy, competent, and justified in their drumbeat of confident statements that "We know how to stop Ebola."

During this phase, US hospitals had numerous rule-out-Ebola false alarms and even more numerous drills. The celebratory proclamations of hospital officials contributed to the public's confidence. The headlines were virtually identical: "California hospitals say they are ready for Ebola, if it shows up"; "Colo. hospitals say they're prepared for Ebola."

But during this same period, some healthcare workers and state public health officials started (quietly) voicing concerns about the Ebola infection control measures recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and about hospital readiness to manage Ebola cases.

On Aug 5, the day Writebol arrived at Emory University, the CDC held a Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity (COCA) call. Throughout the call, CDC officials were emphatic that familiar infection control equipment and procedures would be sufficient to manage Ebola patients. Many of the clinicians who called in asked tough questions about whether those familiar precautions would be enough. At the end of the call, there were still more than 90 questions in the queue.

By the end of August, several state health officials had contacted us about the CDC's Ebola infection control risk communication. Their message: "Our healthcare workers are not buying what the CDC is selling—and we aren't either."

And on Sep 24, while Eric Duncan was incubating Ebola in Dallas, nurses in Las Vegas held a "die-in" to warn that the nation was not ready for an Ebola outbreak.

US public interest in Ebola naturally escalated after Sep 30, when Duncan was diagnosed as having Ebola at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. But it wasn't the mere fact that the country now had its first domestic case that provoked the ensuing strong public reaction. The CDC had done a good job of warning that there would probably be a domestic case sooner or later. Rather, the reaction was fueled by a sequence of seemingly improbable mistakes: the fact that the Presby emergency room had sent Duncan home on Sep 26, after missing that he was a recently arrived visitor from Liberia; the fact that two nurses who treated Duncan somehow caught the disease from him, despite having worn the recommended personal protective equipment (PPE) and followed the recommended protocols; the fact that one of the nurses was permitted to fly to Ohio and back with a low-grade fever.

Mistakes happen in crisis situations. The CDC and the US healthcare system were facing Ebola together for the first time; they were climbing a steep learning curve. But they had led the public to expect something much smoother, much more flawless. When CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, said in an Oct 2 CNN op-ed that he was "confident we will stop Ebola in its tracks here in the United States," he may have meant "…with some inevitable screw-ups and policy changes along the way." But he certainly didn't say so. He set a standard that response efforts could not meet.

The US Ebola experience highlights four main crisis communication errors.

1. Don't over-reassure

Over-reassurance backfires in two ways. Some people smell a rat immediately; their response to over-reassurance is to feel "handled" rather than leveled with, and therefore to become all the more alarmed. Others let themselves believe the over-reassurance until something happens that proves it wrong; then they feel betrayed and all the more alarmed.

To avoid these reactions, crisis communication experts advise officials to err on the alarming side. Official alarmism has its own problems, especially post-hoc accusations of hype; the CDC has experienced some of that with regard to its effort in September to model a West Africa Ebola worst-case scenario, which yielded numbers of up to 1.4 million cases in the region by Jan 20, 2015.

But it's not damned if you do (warn people about risks and even about worst-case scenarios) and damned if you don't. It's darned if you do and damned if you don't. Over-reassurance erodes public trust far more than alarmism. Paradoxically, over-reassurance also exacerbates public alarm more than alarmism.

The most vivid examples of Ebola over-reassurance by US officials came before the October 2014 crisis of confidence, especially in Frieden's words. At a Sep 30 news conference after Duncan was diagnosed in Dallas, Frieden famously said: "Ebola is a virus that is easy to kill by washing your hands. It's easy to stop by using gloves and barrier precautions…. And that's why at the hospital in Texas, they're taking all of the precautions they need to take to protect healthcare workers who are caring for this individual."

At that news conference Frieden talked about stopping Ebola "in its tracks" three separate times. The CDC is a fervent believer that communicators should repeat their key messages as much as possible. The CDC's unique jargon for this contention is SOCO: Single Overriding Communication Objective. Stopping Ebola in its tracks was clearly a linchpin of Frieden's Sep 30 SOCO.

Many observers have noted these and other examples of official Ebola over-reassurance. But most haven't drawn the connections between official over-reassurance and public overreaction. We think those connections are crucial.

Official over-reassurance exacerbates public overreaction. Arguably it even justifies public overreaction. If officials seem to think everything is under control when it obviously isn't, individuals sensibly try to figure out what additional controls might be useful—and then demand them (eg, travel restrictions and quarantines) or take them themselves (occasionally even to the extent of homemade PPE).

Once people realize that officials are understating the seriousness of the problem, they also try to figure out whether officials are more worried than they're letting on, or whether they're simply wrong. That is, to what extent is official over-reassurance a candor problem, and to what extent is it a competence problem? Both are common.

But it's clear that CDC Director Frieden believed what he said. CDC policies matched Frieden's claims—vis-a-vis the ability of US hospitals to manage Ebola patients, what PPE they would need, what sort of monitoring (if any) should be imposed on healthcare workers who treated Ebola patients, etc.

The CDC's pre-Dallas policies were promptly changed once they proved inadequate. But Frieden hadn't warned that errors and policy reversals were to be expected as officials climbed the Ebola learning curve. Instead, he reiterated often his contention that Ebola was well-understood and would succumb to tried-and-true public health measures.

(By contrast, after some initial overconfident over-reassurances during the 2001 anthrax attacks, Frieden's predecessor Jeff Koplan, MD, MPH, warned that public health officials would learn things in the coming weeks that they would then wish they had known when they started.)

So the CDC's errors and reversals looked incompetent, and the impression of CDC incompetence left the public devising its own Ebola response strategies.

2. Acknowledge uncertainty

As the preceding comparison of Frieden and Koplan demonstrates, Ebola over-reassurance was aggravated by Ebola overconfidence.

In an Oct 20 Houston Chronicle op-ed on the CDC's Ebola communication performance,former CDC health marketing director Jay Bernhardt, PhD, MPH, wrote: "A major challenge of risk and crisis communication is finding the right balance between controlling public fear with confident pronouncements and sharing the reality that the experts can't know everything and are making difficult judgments quickly, some of which will turn out to be wrong."

We think Bernhardt's frame—that officials must "balance" the need to sound confident against the need to acknowledge uncertainty—is mistaken. The goal of (over)confident pronouncements is indeed to control public fear, as Bernhardt suggests. But confident statements that turn out wrong exacerbate public fear. Effective crisis communicators acknowledge uncertainty; the best ones go out of their way to proclaim uncertainty. They do it in a confident tone, showing they can cope with the uncertainty and helping the public cope with it too.

Instead of proclaiming Ebola uncertainty, the US public health establishment proclaimed Ebola absolutism. The media were inundated with overconfident assertions about what "the science" proves about Ebola. Nearly all these assertions converted accurate generalizations about how Ebola usually or almost always behaves into what sounded like ironclad laws about how it always behaves. It (always) has an incubation period of 2 to 21 days; it is (always) transmitted through direct contact with bodily fluids; etc.

When experts start talking about "the science" instead of just "science," it's often a tipoff that they're about to attack as unscientific some opinion with which they disagree. In late October, the most frequently attacked opinion was that asymptomatic healthcare volunteers just back from treating Ebola patients in West Africa should be quarantined.

We don't have room here to review the scientific evidence for and against Ebola quarantines. (Interested readers might want to look at Ebola in the U.S. (so far): the public health establishment and the quarantine debate.) But the strongest scientific anti-quarantine argument is that asymptomatic people rarely if ever transmit Ebola. The strongest pro-quarantine scientific arguments are that people with Ebola sometimes hide or misinterpret their symptoms (as Nigerian doctor Ada Igonoh did after treating Patrick Sawyer in Lagos) and that Ebola is often characterized by sudden onset of symptoms (as both the CDC and World Health Organization case descriptions specify).

The case of Craig Spencer, MD, in late October demonstrates all three points. Despite being out and about in New York City the day before he was diagnosed with Ebola, Spencer infected nobody—yet another example of asymptomatic non-transmission. On the other hand, Spencer later said he "felt sluggish" the day before he went out on the town. It's not clear if he decided his sluggishness wasn't a symptom or if he reported it to someone at Doctors without Borders who decided it wasn't a symptom. The morning after his outing, Spencer had simultaneous abrupt onset of a low fever (100.3ºF) and diarrhea. He called in his symptoms and was transported to Bellevue Hospital, where he was isolated and tested positive for Ebola the same day. (See the New York City news conference transcripts for Oct 23 and Oct 24.)

If Spencer's sluggishness was an Ebola symptom, he missed it. If it wasn't an Ebola symptom, his symptoms came on suddenly and it was lucky he happened to be home then, with easy access to a private bathroom.

Bottom line: There is science on both sides of the quarantine debate—and no excuse for either side to be uncivil or absolutist. And of course any debate over "how safe is safe enough" is fundamentally about values, not science.

To varying degrees, science is always provisional. Ebola science is highly provisional. As statisticians remind us, distributions have tails as well as a hump; the hump is what usually happens and the tails are the outliers. With regard to Ebola, we know a great deal about what usually happens, at least in Africa. We know very little about the outliers—there are too little data to distinguish unusual occurrences from impossible ones.

Here's a thought experiment for public health professionals: Imagine an incontrovertible exception to one of your Ebola absolutes—someone gets the disease after an incubation period of longer than 21 days; someone transmits it while his or her own symptoms are still mild; someone catches it via a cough or a sneeze.

Would you be shocked? Would you judge that our scientific understanding of Ebola has been rocked to its foundations? Or would you acknowledge the exception as simply an outlier, too unusual to be a sound basis for policymaking but not incompatible with anything fundamental about Ebola science as we know it? Would you, in fact, belatedly tell the public something like "We're not surprised that…."?

By their absolutism, officials and experts are setting up the public to be shocked by such exceptions—and to see them as further evidence that those in authority are lacking in competence, caution, and/or candor. That's a recipe for mistrust and overreaction. If experts and officials want the public to trust "the science," they must trust the public with a less absolutist depiction of what science tells us about Ebola.

3. Don't overdiagnose or overplan for panic

Everyone has seen the news stories about US individuals and organizations that took unreasonable Ebola precautions in October—the woman at the airport in her homemade PPE, the school system that thought Zambia might be in West Africa, etc. We don't dispute that some people and some local officials took obviously excessive Ebola precautions.

Most didn't. The typical American (even in Dallas and New York City) was interested in Ebola, a little anxious, and maybe a little titillated. But very few stocked up on supplies in anticipation of a US epidemic, and very few changed their daily routine. When asked by pollsters, most Americans said they supported Ebola policies (such as quarantine) that most experts consider an overreaction. But comparatively few Americans "overreacted" in their actual behavior.

When public health professionals claimed that the country was in a panic, they were treating the outliers as if they were typical. (Reporters unsurprisingly did the same thing, reporting as representative the most far-out tweets they could find.) There's a certain crazy symmetry in the fact that the public health establishment ignored the possibility of outliers on the Ebola transmission spectrum while overstating the prevalence of outliers on the Ebola public response spectrum.

Even these atypical public overreactions weren't examples of panic. Panic is doing something seriously harmful to self or others that you know is seriously harmful to self or others, but your level of emotional arousal is so strong you just can't help yourself. Getting off a bus because someone a few seats away looks ill and West African is unnecessary and even cruel, but it's not panic. Panic is if you don't wait for the bus to stop before you get off.

Social scientists who study emergency management have known for decades that panic is comparatively rare. Articles and book chapters about "the myth of panic" have been appearing since the 1950s. (For a readable online example, see this 2002 article by Lee Clarke, PhD.) However panicky they may feel, most people behave sensibly in emergencies. But official "panic panic"—misdiagnosing an overcautious and possibly mistrustful public as panicking or about to panic— is widespread.

A number of reporters contacted us in October for comment about the public's Ebola panic. In each case we asked the reporter whether he or she knew anyone personally who had panicked. The answer was always no. But reporters had read about a small number of quasi-panicky reactions. And they'd seen quotes from public health experts noting and mocking the public's panic. So it must be real, right? No, actually, wrong.

For the longest and best of our published responses to the Ebola panic question, see How rational are our fears of Ebola?

4. Tolerate early overreactions; don't ridicule the public's emotions

So if they weren't panicking, what were Americans—some Americans—doing in October? They were having an adjustment reaction, a temporary overreaction to a new scary situation, exacerbated by leaders who kept sounding over-reassuring and overconfident, while looking under-competent and untrustworthy.

What's the proper public health response to people's adjustment reaction? Certainly not to ridicule it!

Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, of the Harvard School of Public Health crystallized the ridicule response on Oct 24, when he told Sarah Kliff of Vox: "I'm a believer in an abundance of caution but I'm not a believer of an abundance of idiocy." Kliff's article, focused largely on the case that Ebola quarantines are foolish, was entitled "The New York Ebola patient is a hero. Stop criticizing his bowling trip." The "abundance of idiocy" quote was widely requoted and retweeted. Other expressions of contempt for the public's Ebola fears included labels like "hysteria," "panic" (of course), and even "insane."

Instead of trying to squelch the adjustment reaction contemptuously, seasoned crisis communicators try to guide it empathically—to help people figure out which aspects of a scary situation are most serious and which precautions are most sensible. For Ebola, this would have meant seizing the teachable moment presented by the US public's brief preoccupation with Ebola to mobilize greater concern about the epidemic in West Africa and its possible spread to other developing countries.

Public health professionals did try to deflect Americans from focusing on Ebola in their backyards to focusing on Ebola in West Africa. Or on flu. Or on auto accidents. On anything, in fact, instead of Ebola in their backyards. In short, the effort to harness and redirect the public's Ebola fears was hobbled by contempt rather than empathy for the public's Ebola fears.

The tougher question is whether public policy should take note of public fears. President Obama was neither the first nor the last to intone (on Oct 25) that the US response to Ebola must "be guided by facts, not fear." In other words, we should do what public health professionals think best, not what the public thinks best. Fair enough—though arguably the US public and a few governors were ahead of the CDC in deciding that returning volunteers needed to be monitored carefully, not trusted to monitor themselves.

But public health professionals seemed systematically confused about the relevance of Ebola fears to Ebola policy. Many were apparently comfortable making over-reassuring and overconfident statements to assuage people's fears (rarely noticing that these practices backfire). But taking precautions to assuage people's fears—airport thermal screening, for example—struck the very same experts as unacceptably unscientific. If fear is itself a threat to health, as David Ropeik among others has argued, then isn't there a scientific, public health basis for policies that calm people's excessive fears?

In the debate over Ebola quarantine policy, the dominant position of public health professionals has been even more confused. Leave aside whether a quarantine might protect against an Ebola sufferer whose symptoms have been missed or appear suddenly. Focus instead on how quarantining a volunteer just back from West Africa might affect the fears of that volunteer's neighbors, 80% of whom support Ebola quarantines.

We agree fervently that trying to assuage neighbors' fears (and to reduce stigma) isn't a good enough reason to restrict the freedom of returning volunteers, perhaps deterring prospective volunteers in the process. But most public health critics of Ebola quarantines haven't even acknowledged that calming excessive public fears is a useful byproduct of Ebola quarantines. Instead, they have accused the pro-quarantine side of fearmongering.

It is inconceivable to us—and contrary to much risk communication theory and research—that people who are demanding that returning volunteers be quarantined would become more alarmed if their demands were met, but would be reassured if they were told their demands are idiotic.

Consider also the remarkable contradiction between what experts and officials told America's healthcare workers and what they told the rest of us.

The appropriate message given to healthcare workers: "Prepare. Imagine an Ebola sufferer walking into your waiting room. Practice donning and doffing your PPE without contaminating yourself, and then practice some more. Ask all patients with fevers if they've been to West Africa recently. Even though the odds of your ever treating an Ebola sufferer are low, you still need to get ready."

Nurses and doctors were rightly instructed to go "Oh, my God" and get through their adjustment reactions now, precisely so they will be ready in case they are needed.

The inappropriate message given to everybody else: "Don't prepare. Don't imagine sitting in the waiting room when an Ebola sufferer walks in and sits down next to you. Don't worry about your daughter the nurse or your neighbor the doctor who has been told to get ready to take care of an Ebola patient. Don't try to figure out what you might do or what your local government might do to reduce Ebola risk in your community. Don't try to figure out where that risk might come from. Focus on how low the odds are of your ever meeting an Ebola sufferer, and then think about something else, la-la-la-la."

The public was instructed to stop having this ridiculous adjustment reaction, to stop trying to be ready in case they are needed.

Treat the public like grownups

Aiming to convince the public that there was no cause for Ebola alarm, officials and experts used overconfident over-reassurance and absolutist invocations of "the science." And then they had the gall to ridicule the public as hysterical and panic-stricken. We hope that before the next unfamiliar and frightening infectious disease arrives, officials and experts will practice treating the public like grownups.

Other crisis communication lessons

Readers interested in our generic crisis communication advice may want to start with this list of 25 recommendations. These recommendations are fleshed out in our 2004 crisis communication video, and in the handouts written to accompany the video.

Here are some of the other recommendations on the list that are relevant to the U.S. Ebola "crisis" of October 2014:

- Share dilemmas.

- Acknowledge opinion diversity.

- Offer people things to do.

- Acknowledge errors, deficiencies, and misbehaviors.

- Don't lie, and don't tell half-truths.

All our writing about crisis communication is listed and linked in our Crisis Communication Index. Our writing specifically about Ebola communication is listed and linked in our Ebola Risk Communication Index.