As the Ebola virus ravaged three West African countries last year, US hospitals faced unexpected challenges adapting to the risks, even the ones that had done preparedness drills, and the threat consumed 80% of infection control staff time, two research teams reported.

The groups detailed their findings yesterday in two reports in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (ICHE). One described the case of two patients with confirmed or suspected Ebola infections at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., and the other involved a survey that questioned infection control specialists about the experiences they had preparing to care for Ebola patients.

In another report today, New York health officials reported on their challenges and lessons learned when a healthcare worker got sick and was hospitalized after returning from Sierra Leone last fall.

NIH staff detail unique Ebola challenges

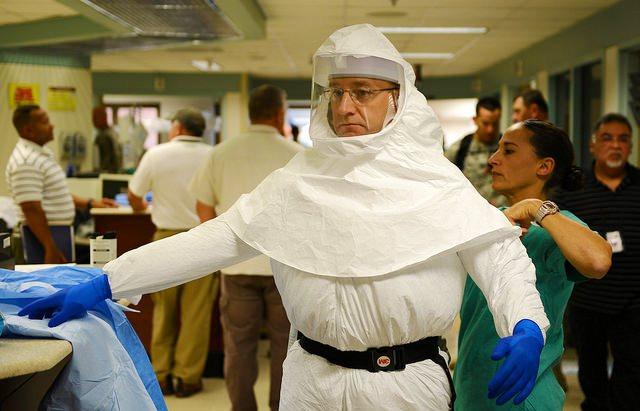

In the first ICHE report, NIH clinicians described their care of a physician who sustained a needlestick injury while working in Sierra Leone who did not develop the disease and of a Dallas nurse who was sickened by the virus while caring for the first Ebola patient diagnosed on US soil, a Liberian man who was visiting the United States.

They noted that the high-containment unit at the NIH hospital was originally designed to treat people after occupational exposure while working on select agents at the agency's nearby labs. Though staff had been planning and practicing to provide specialty care for many years, they said final preparations for receiving potential Ebola patients uncovered many surprises.

For example, a surge of interest from the media made it hard to maintain patient confidentiality, and the staff didn't expect the high volume of calls from other medical centers and the public. Calls to the unit required a full-time staff member, and in retrospect, should have been limited, the authors said.

The team said the admissions stoked a high degree of anxiety and hysteria that resembled reactions seen in when the center studied AIDS patients in the 1980s. Though the fear of the unknown among the public and staff is understandable, they noted that the difference with Ebola is that much more is understood about the virus that causes the disease and how it is transmitted.

"The keystone of our approach was transparency," the group wrote. "We answered questions saying, 'We don’t know,' when we didn’t know the answer, but we promised to try to find the answer, if it existed." They added that the anxieties can be paralyzing if not acknowledged and handled with calmness and candor.

An all-volunteer staff handled patient care, but managers worried whether that system could cover around-the-clock staffing needs. The team appointed specially trained members to observe doffing procedures—thought to pose the greatest risk—but the after-midnight shifts were difficult to fill.

Training a large number of staff was also a challenge, and the NIH prioritized those who would be providing direct patient care or handling specimens.

After a warning from colleagues at Emory University Hospital that waste generated during Ebola patient care would be "enormous," the NIH group had 2 weeks to plan for that element before they received their first patient. They said more than 170 bags of waste were filled and autoclaved during one 10-day admission.

The team ran into an unexpected bottleneck with the landfill owner refused to accept incinerated ashes, which prompted the incinerator contractor to turn away the NIH's sterilized medical waste.

Survey reveals preparedness gaps

Some of the NIH experiences were echoed in responses to an e-mail survey sent to Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) members near the end of October. The results, based on responses from 257 of 1,973 members, were also published in ICHE. Respondents represented health facilities in 41 states, the District of Columbia, and 18 different countries.

They found that preparedness exercises, response plan development, staff training, and keeping up with changing national guidelines took up 80% of infection control staff time, leaving time for only 30% of routine infection prevention activities during that period.

Survey responses revealed gaps in preparedness. Though 65% of respondents reported hosting drills and exercises to help staff prepare, only 30% of frontline care providers had been trained in adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) use, and less than half of the hospitals had the capacity to test patients with suspected Ebola infection.

More than a quarter of patients who were evaluated for Ebola faced care delays or limits in management for other medical conditions.

Hospitals felt only moderately prepared. Of 141 hospitals that had evaluated patients for Ebola, only 2 diagnosed unrecognized Ebola, and 5 had cared for patients with confirmed infections.

Researchers said the limited level of PPE training raises concerns for preparedness for other pathogens, and because so few patients were evaluated with even fewer confirmed, national leaders should consider if general emerging pathogen preparedness would be more cost effective.

Interagency coordination, a key response step

In a report today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), experts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and their partners in New York highlighted lessons learned during the isolation and hospitalization of Craig Spencer, MD.

Spencer got sick with Ebola in late October after returning from Sierra Leone, where he had worked with Doctors without Borders (MSF). The city's health department had activated its incident command system soon after the first Ebola case was detected on US soil in late September in Texas.

New York City health department investigators used the date of Spencer's fatigue onset—2 days before he developed a fever—as the exposure time for potential contacts, given their knowledge of the disease and their desire not to miss any contacts. Three personal contacts were identified for active monitoring, and 114 healthcare workers underwent active monitoring.

The authors wrote that the public health response to Spencer's illness underscored the importance of interagency collaboration. For example, the city's health department and MSF had already established a protocol for when an MSF worker in New York City met investigation criteria.

Despite strong planning and cooperation, the groups involved in managing Spencer's illness faced several challenges. For example, it was difficult to create clear, implementable criteria to determine which health workers needed monitoring, the authors said. And data flow between the health department and the hospital initially required 12 full-time staff members.

The group noted that the quickly evolving situation created gaps in instructions for workers who needed active monitoring but were planning to travel, especially against the backdrop of changing guidelines at different levels on movement restrictions for those who had contact with Ebola patients.

See also:

Apr 1 Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol abstract on NIH Ebola patients

Apr 1 Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol abstract on SHEA survey

Apr 1 SHEA press release on the above studies

Apr 3 MMWR report