A detailed report on a cluster of unexplained polio-like illnesses in Colorado children supports, but doesn't prove, the suggestion that they were linked with enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), which caused a nationwide outbreak of respiratory ailments in children in the late summer and fall of 2014.

Writing in The Lancet, physicians from Children's Hospital Colorado describe 12 cases of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) and cranial nerve dysfunction (facial weakness and/or difficulty swallowing) that occurred in children from August through October of last year. Five of the children tested positive for EV-D68, and of 10 who had limb weakness, none have fully recovered.

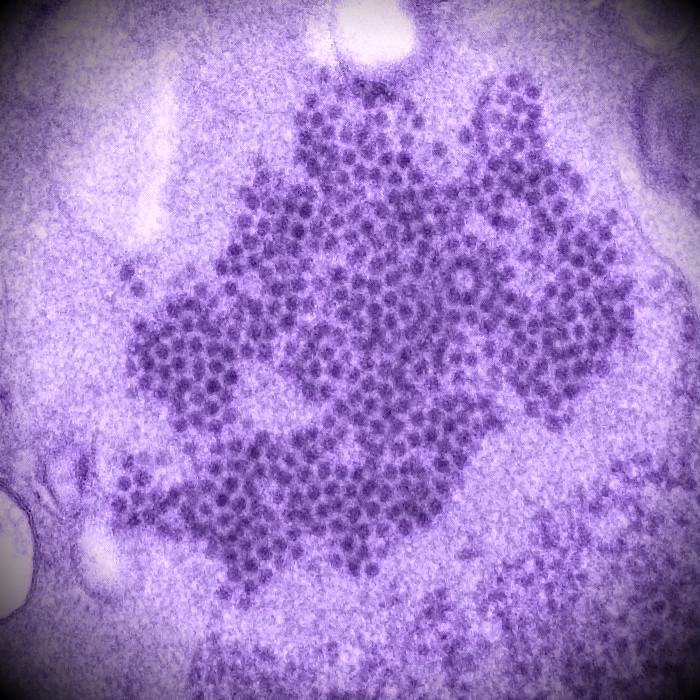

The cases coincided with an outbreak of EV-D68 infections at the Colorado hospital and around the country. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has counted 1,153 EV-D68 respiratory infections in 49 states and the nation's capital since mid-August, nearly all of them in children.

The CDC also has reported 107 cases of the unexplained polio-like illness, which it calls acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), in 34 states since August. Some of these patients tested positive for EV-D68, but the agency has not reported any firm conclusions about a causal link between the virus and the polio-like disorder.

In the Lancet report, the authors, who include two CDC experts, write, "Our findings suggest the possibility of an association between enterovirus D68 and neurological disease in children. If enterovirus D-68 infections continue to happen in an endemic or epidemic pattern, development of effective antiviral or immunomodulatory therapies and vaccines should become scientific priorities."

A clear spike in cases

Aiming to assess the possible link between neurologic illness and the virus, the researchers examined data on children who were admitted to their hospital for treatment of AFP or acute cranial nerve dysfunction with onset between August and October of 2014. The case definition specified AFP accompanied by gray-matter lesions in the spinal cord or cranial nerve dysfunction with brainstem lesions on imaging.

They found 12 children with cases that met their definition. In combing data from the 4 years preceding the study period (Jul 31, 2010, to Jul 31, 2014)—used as a historical control period—they found that the incidence was three times as high as in any 3-month period during those 4 years, a significant difference.

Nine of the 12 patients were boys, and the median age was 11.5 years. Eight were previously healthy, while three had a history of asthma and one had had a heart transplant. All but one child had received all their childhood vaccines, including polio; the other one had had no vaccinations.

All of the children had had a febrile illness with nasal congestion, a cough, or sore throat that began a median of a week before the neurologic problems surfaced.

Ten of the 12 children had varying degrees of weakness in their arms and/or legs, often associated with pain, but they had no loss of sensation. The same number had a cranial nerve dysfunction as manifested by defective speech, trouble swallowing, double vision, or facial droop.

Spinal-cord lesions were seen on imaging in 11 children, and brainstem lesions were observed in 9. The spinal cord lesions were extensive, spanning a median of 17 vertebral levels.

Virus found in respiratory samples

The authors obtained nasopharyngeal samples from 11 of the 12 children a median of 10 days after their initial febrile illness. Eight of these tested positive for a rhinovirus or enterovirus, and 5 of the 8 were positive for EV-D68. The team also looked for the virus in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 11 patients and the blood of 7, but all the results were negative.

The physicians tried several treatments, including intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin, IV methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, and the experimental antiviral drug pocapavir, which was developed for polio. But none of these seemed to help, the report says.

It says some of the patients have experienced mild improvement in their limb weakness with the help of physical therapy. Senior author Samuel Dominguez, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and microbial epidemiologist at Children's Hospital Colorado, told CIDRAP News that the patients have had some continued improvement, but none have fully recovered normal arm and leg motion.

He added that two children who had isolated cranial nerve involvement have recovered function of those nerves.

In other observations, the authors note that they identified 16 cases that met their case criteria during the 4-year historical control period. Nasopharyngeal samples were taken from six of these children, and one of these, dating to November 2013, was available and tested positive for EV-D68.

Reasons for suspecting EV-D68

"Although our findings do not prove that enterovirus D68 is the cause of the neurological presentations described, several epidemiological, virological, and clinical factors suggest an association between the D68 virus and neurological disease," the report states.

The factors include the relatively high number of children meeting the case definition during the EV-D68 respiratory disease outbreak in Colorado, the respiratory illness that preceded the neurologic illness, and the confirmation of EV-D68 in five patients.

Dominguez said no more polio-like cases have occurred at the hospital since the end of October. "If enterovirus 68 potentially has a role, we would've expected the neurologic cases to go away when the respiratory cases went away, and that's what happened," he added.

The report also says the pattern of neurologic deficits and neuroimaging abnormalities is distinctive and similar to what is seen with certain other enteroviruses that affect motor nerve cells, including poliovirus and enterovirus A71.

However, the detection of EV-D68 in some of the patients may have been merely coincidental, particularly since the virus was not found in their CSF, which precluded a firm conclusion about the virus's role, the report says.

If EV-D68 is in fact the cause of the polio-like illness, there are several possible explanations of why very few similar cases have been seen before, the authors say. Among them are improved tests and the possibility of a new strain of the virus.

They conclude that their findings expand the potential range of EV-D68 disease, adding, "If further investigation confirms the association between enterovirus D68 and acute flaccid paralysis and cranial nerve dysfunction, enterovirus D68 will be added to the list of non-poliovirus enteroviruses capable of causing severe, potentially irreversible, neurological damage."

In an accompanying editorial, two French virologists, Audrey Mirand, PharmD, PhD, and Helene Peigue-Lafeuille, MD, PhD, comment that the failure to find EV-D68 in the patients' CSF might have been due to the delay in collection of samples by a median of 10 days after the respiratory illness. They work at the National Reference Center for Enteroviruses and Parechoviruses in Clermont-Ferrand, France.

They add that the absence of EV-D68 in CSF samples does not necessarily rule out a causal role for the virus, "because poliovirus and enterovirus A71 are also more frequently recovered in peripheral samples (stool or throat swabs)."

Dominguez said the hospital has established a multidisciplinary clinic for continued monitoring of the AFP patients. In ongoing investigations, the team is collecting serum samples to test the patients for EV-D68 antibodies, and they may also do a case-control study to examine the prevalence of EV-D68 antibodies in the community, he reported.

Messacar K, Schreiner TL, Maloney JA, et al. A cluster of acute flaccid paralysis and cranial verve dysfunction temporally associated with an outbreak of enterovirus D68 in children in Colorado, USA. Lancet 2015 (Early online publication Jan 29) [Abstract]

Mirand A, Peigue-Lafeuille H. Acute flaccid myelitis and enteroviruses: an ongoing story. Lancet 2015 (Early online publication Jan 29) [Excerpt]

See also:

Related CIDRAP News items and stories: