Researchers inched closer to understanding the cause of a mysterious limb-weakening condition that has led to a rash of cases, mainly in kids, in the late summer and fall every other year since 2014, revealing new findings today based on new spinal fluid testing methods.

One of the new tools didn't find much direct evidence of enterovirus in the samples, but a new microchip testing method designed to detect antibodies resulting from enterovirus infection—an indirect but useful gauge—found evidence in several samples. A team from Columbia University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported their findings today in mBio.

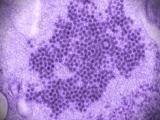

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) affects the spinal cord and is marked by onset of sudden weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in cases have paralleled outbreaks of enterovirus D68 and enterovirus A71, which typically cause a mild respiratory infection. However, no direct cause has been identified.

CDC reports two new cases

In its latest update yesterday, the CDC said 13 AFM cases from 8 states have been confirmed so far this year, an increase of 2 from its report last month. Health officials are still investigating 76 suspected cases. Since the CDC began tracking cases in 2014 it has received reports of 574 illnesses.

Earlier this summer, the CDC issued a statement urging clinicians to be alert for AFM cases in the coming months.

New tests looked for direct and indirect evidence

For the study, researchers used a new tool called VirCapSeq-VERT to look for genetic evidence of the virus in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 13 children and 1 adult diagnosed with AFM in 2018. They also tested five CSF samples of people with other central nervous system diseases. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

They found enterovirus genetic material (EV-A71) in the adult AFM patient and genetic material from another enterovirus called echovirus 25 in one of the non-AFM cases.

Then using a microchip assay called AFM-SeroChip-1 that they developed, they examined samples for enterovirus antibodies. They tested the same 14 AFM samples and looked at CSF samples from 10 adults with central nervous system conditions and 10 children with Kawasaki disease.

They found enterovirus antibodies in 11 of 14 AFM patients, and of those, 6 were positive for EV-D68, a strong indicator that enterovirus had been in the central nervous system. None of the samples from kids with Kawasaki disease had enterovirus antibodies.

In another part of the study, researchers tested CSF samples from the 14 AFM patients and 6 of the controls for tickborne diseases using a new test developed by the Columbia University's Center for Infection and Immunity (CII). All were negative

Though the investigation into other AFM causes continues, the team concluded that the study provides further evidence that enterovirus infection may play a role.

Nischay Mishra, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at CII and the research team's co-lead, said in a Columbia University press release that doctors and scientists have long suspected that enteroviruses, which are relatives of polio virus, are the cause of AFM, but there hasn't been any direct evidence to prove it.

"Further work is needed with larger, prospective studies; nonetheless, these results take us one step closer to understanding the cause of AFM, and one step closer to developing diagnostic tools and treatments," he said.

See also:

Aug 13 mBio study

Aug 13 NIAID press release

Aug 13 Columbia University press release

Aug 12 CDC AFM update

Jul 10 CIDRAP News story "CDC wants clinicians' help to solve acute flaccid myelitis riddle"