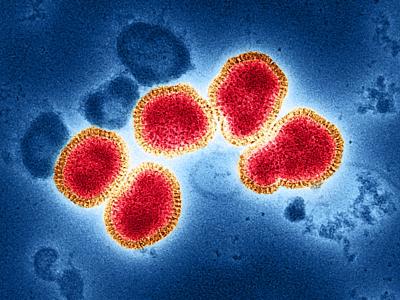

Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of babies exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy showed abnormal findings in 3 of 48, shedding more light on the congenital effects of the virus, according to a study to be presented next week at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting in San Francisco.

In another research development, an international group of scientists identified an antibody against Zika virus that might play a role in the development of treatments and vaccines and explain why some people weren't as affected during recent outbreaks.

Study team to follow long-term development

None of them had microcephaly, the most obvious and dire outcome of fetal exposure to Zika. But the MRI series alludes to one of the key mysteries of pregnancies affected by Zika virus: If a baby looks normal at birth and doesn't have microcephaly, have they been protected against the disease?

"We don't know the long-term neurological consequences of having Zika if your brain looks normal," Sarah B. Mulkey, MD, PhD, a fetal-neonatal neurologist, said in a press release from Children's National Health System. She is a member of the Children's Congenital Zika Virus Program, which scanned the 48 babies for the study, and will present the group's findings on May 9. "That is what's so scary, the uncertainty about long-term outcomes."

Of the 48 babies selected for the study, all appeared healthy and had mothers with confirmed Zika infection in pregnancy. Forty-six mothers were Colombian, and two were Americans who contracted the disease while traveling to a Zika hot zone. The women experienced Zika symptoms at a mean gestational age of 8.4 weeks, and all had at least one fetal ultrasound performed in pregnancy.

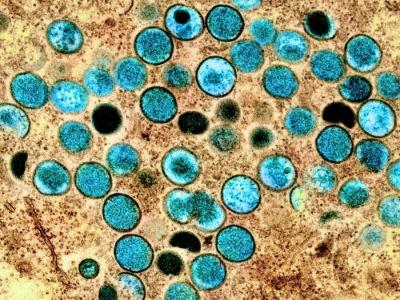

Only three fetuses exposed to Zika in the first or second trimester had abnormal fetal MRI results. One fetus' MRI showed heterotopia and "an early, abnormal fold on the surface of the brain." The pregnancy was terminated at 23.9 weeks. The second had parietal encephalocele, a birth defect that causes the brain to protrude from the skull. According to the researchers, "it is not known if this rare finding is related to Zika infection."

Finally, a third fetus had a number of abnormal brain findings, including a thin corpus callosum, dysplastic brainstem, heterotopias, significant ventriculomegaly, and generalized atrophy.

"Fetal brain MRI detected early structural brain changes in fetuses exposed to the Zika virus in the first and second trimester," Mulkey said. "The vast majority of fetuses exposed to Zika in our study had normal fetal MRI, however. Our ongoing study, underwritten by the Thrasher Research Fund, will evaluate their long-term neurodevelopment."

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that 1 in 10 babies born to a Zika-infected mother will have congenital complications from prenatal exposure to the virus. Long-term prognoses for these children are unknown.

Antibody could help vaccine development

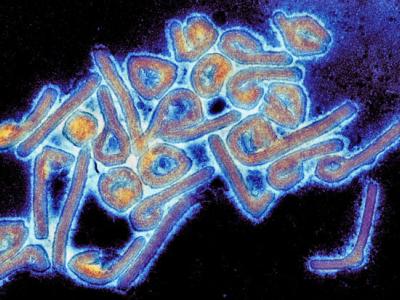

Investigators from the Rockefeller University have identified antibodies in the blood of people infected with the Zika virus in Brazil and Mexico that appear to block infection. The finding could help researchers create new tools to fight the virus, including a vaccine.

In the study, published in the journal Cell, today, the investigators describe how five of six volunteers produced nearly identical antibodies that were uniquely primed to fight the Zika virus. The antibody, called Z004, was then given to mice exposed to Zika, and it protected them from developing infections.

When the research teams explored and mapped the interaction between the antibody and Zika virus, they found that the antibody pinches a ridge on the virus during binding. The ridge is also present on other flaviviruses, and they found that the ridge on dengue 1 is remarkably similar to Zika.

Researchers said a tiny fragment of Zika envelope protein containing the ridge might offer vaccine developers a safer approach than ones that all or most of the virus to prompt an immune response.

Z004 also offered protection against dengue 1, and further analysis of the blood samples from Brazil showed that many who had mild Zika infections were previously infected with dengue 1, which they said might explain why some people fared better during the outbreak.

Margaret MacDonald, MD, PhD, a research associate at Rockefeller and a study coauthor, said in the press release, "Even before Zika, their blood samples likely had antibodies that could interact with this same spot on the envelope protein. It appears that, much like a vaccine, dengue 1 can prime the immune system to respond to Zika."

See also:

May 4 Children's National Health System press release

May 4 Cell study

May 4 Rockefeller University press release