As many as 1 in 100 hospitalized COVID-19 patients may experience a pneumothorax, or punctured lung, according to a multicenter observational case series published yesterday in the European Respiratory Journal.

Pneumothorax usually occurs in very tall young men or older patients with serious underlying lung disease. But University of Cambridge researchers identified COVID-19 patients with neither of those traits who had a punctured lung or pneumomediastinum (air or gas leakage from a lung into the area between the lungs) from March to June at 16 UK hospitals.

"We started to see [COVID-19] patients affected by a punctured lung, even among those who were not put on a ventilator," said Stefan Marciniak, MB BChir, PhD, from the University of Cambridge in a news release. "To see if this was a real association, I put a call out to respiratory colleagues across the UK via Twitter. The response was dramatic—this was clearly something that others in the field were seeing."

Sixty of 71 COVID-19 patients included in the study had a punctured lung, including two with different episodes of pneumothorax, for a total of 62 punctures. Six of the 60 patients with pneumothorax also had pneumomediastinum, while 11 patients had only pneumomediastinum.

Age, acidosis, and survival

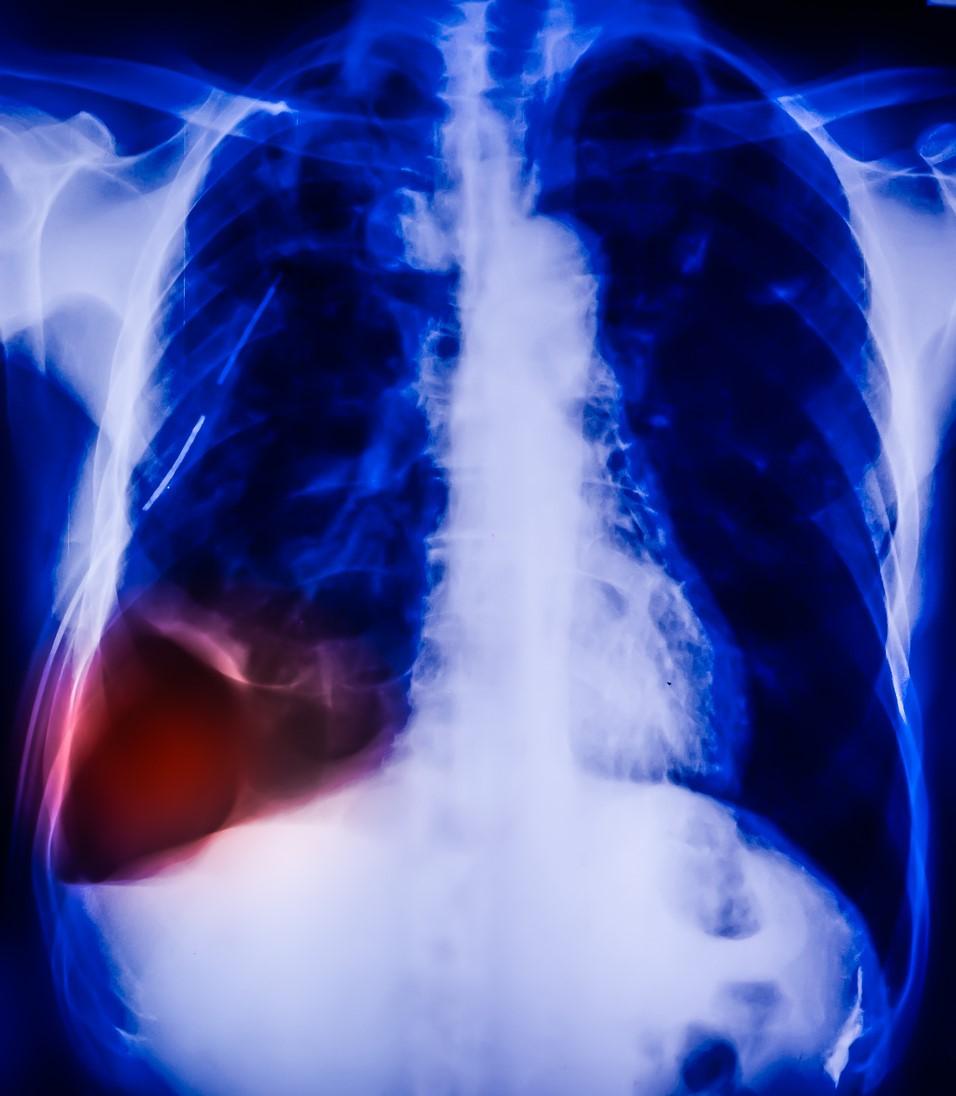

Nine patients with shortness of breath on arrival at the hospital were diagnosed on chest x-ray as having punctured lung, 5 of them hospital readmissions after COVID-19 treatment (4 patients) or becoming infected with coronavirus in the hospital (1). All patients in this group were older than 40 years, and only two had underlying lung disease.

Seven of the nine patients required a chest drain. Two (22%) died 7 and 10 days after pneumothorax, one not requiring a chest drain and one having had the drain removed after the pneumothorax healed. The remaining seven patients were released from the hospital after a median stay of 7 days.

Fourteen patients experienced pneumothorax during their hospitalization while breathing on their own on a general or respiratory ward; six of them were diagnosed by chance. Three patients were on noninvasive ventilation at diagnosis. Eleven patients needed chest drains, while one required surgical intervention. Three patients (21%) died, the rest were released from the hospital after a median stay of 35 days, and one was later readmitted because of pneumothorax of the other lung.

Thirty-eight patients had a total of 39 lung punctures while receiving invasive ventilation; 26 needed invasive ventilation only, while 12 needed oxygen added to their blood outside their body.

Of the 26 patients requiring only invasive ventilation, punctured lung was diagnosed by chance or because they needed more oxygen, revealing hypercapnia (excess carbon dioxide caused by breathing that is too shallow or slow) and acidosis, a buildup of acid caused by lung or kidney dysfunction. Seven patients were given a chest drain, and eight survived for at least 28 days.

There was no significant difference in 28-day survival after punctured lung or pneumomediastinum (63.1% vs 53%; P = 0.85) or between men and women (62.5% vs 68.4%, P = 0.62). However, men were three times more likely to have pneumothorax than women, which the authors said might be because men with COVID-19 appear predisposed to more severe disease. No patients required treatment for pneumomediastinum.

Patients 70 years and older had only a 41.7% survival rate, compared with 70.9% in younger patients (P = 0.02), and patients with acidosis had only a 35.1% chance of 28-day survival, versus 82.4% of their peers, regardless of age.

Serious but treatable condition

The authors noted that previous small retrospective studies suggested that punctured lungs might occur in 1% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients and those dying from their infections and 2% of those needing intensive care, while another study estimated rates of barotrauma (both pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum) at 15%.

A case report yesterday out of China highlights the importance of being on guard for spontaneous pneumothorax, or sudden collapsed lung, especially in COVID-19 patients who have prolonged severe lung damage.

Studies have also suggested that other coronaviruses may contribute to pneumothorax. In a 2004 study, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was also associated with spontaneous pneumothorax, occurring in 1.7% of hospitalized patients. Likewise, in a 2015 study, a punctured lung was considered a predictor of a poor prognosis in patients with MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome).

The authors of the new study said that COVID-19 may cause cysts in the lungs that could lead to lung punctures. They advised doctors to consider the possibility of punctured lungs in COVID-19 patients, even in those who don't fit the profile for it, as many study patients were diagnosed with this condition only by chance.

While an observational case series can't prove that COVID-19 causes pneumothorax, the authors said that the number of affected patients in their study make it unlikely that all lung punctures were coincidental. They said that if there were no link between the two conditions, they would likely have observed only 18 cases of punctured lung in COVID-19 patients from Jan 22 to Jul 3.

While previous studies have suggested that pneumothorax is a predictor of poor outcomes, the authors noted that study patients had an overall 63.1% survival rate and that 52% were released from the hospital.

"These cases suggest that pneumothorax is a complication of COVID-19," they wrote. "Pneumothorax does not seem to be an independent marker of poor prognosis and we encourage active treatment to be continued where clinically possible."

Co-author Anthony Martinelli, MB BChir, a respiratory physician at Broomfield Hospital, said in the news release, "Although a punctured lung is a very serious condition, COVID-19 patients younger than 70 tend to respond very well to treatment. Older patients or those with abnormally acidic blood are at greater risk of death and may therefore need more specialist care."