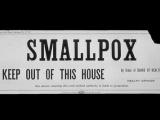

Jan 31, 2003 (CIDRAP News) – A case described in this week's New England Journal of Medicine illustrates some practical obstacles to quick diagnosis of illnesses that look like smallpox, including potential problems in sending clinical samples to outside laboratories for analysis.

The case involved a man who reported to MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland with a rash that had started on his face after four days of headache, fever, nausea, and vomiting, according to a letter by Jennifer A. Hanrahan, DO, and two colleagues. The symptoms suggested possible smallpox, and the hospital notified local health officials and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The hospital lab tested clinical specimens for varicella-zoster virus and HIV and got negative results. The staff e-mailed digital photos to the CDC and also sent clinical specimens. The CDC cultured the specimens and identified the pathogen as herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2 (human herpes virus 2), usually associated with genital herpes.

"The collection and shipping of specimens were more complex than we had anticipated," wrote the authors, who followed CDC guidelines in sending the material. "Not all items listed by the CDC as necessary for the collection of specimens are generally available in hospitals, so it is worth reviewing this list ahead of time."

The authors said it took considerable time to collect the appropriate specimens and then complete the detailed paperwork that's needed when sending specimens via commercial shipper to the CDC. In all, it took 25 hours from the time health departments were notified of the case until the CDC notified the hospital of its finding, the letter states. "Had this event not occurred during normal business hours, the process could have taken even longer."

The letter says it would not have been necessary to send specimens to the CDC if the hospital had conducted direct fluorescence antibody tests for HSV. In a Reuters Health report, Hanrahan was quoted as saying she decided against testing the patient for HSV because, with the possibility of smallpox, she wanted to limit lab workers' exposure to clinical specimens.

In view of this case, the hospital has instituted a protocol for rapid evaluation of patients with febrile illnesses that suggest possible smallpox; the protocol includes tests for HSV as well as varicella-zoster virus and syphilis.

In an accompanying letter, CDC officials comment that the case demonstrates the usefulness of digital cameras and shows that public health labs need rapid diagnostic tests for the full range of diseases included in the differential diagnosis of smallpox. "The appropriate diagnosis would have been made hours earlier in this case if a test for HSV had been readily available," states the letter by Inger Damon, MD, PhD, and colleagues.

The CDC officials echo Hanrahan's advice to review the guidelines for collecting and shipping specimens in order to speed that process. "When indicated, aircraft are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to move specimens to reference laboratories or physicians who can assist in the evaluation of patients," the letter notes.

Hanrahan JA, Jakubowycz M, Davis BR. A smallpox false alarm. (Letter) N Engl J Med 2003;348(5):467-8

See also:

CDC guidelines for specimen collection and transport

http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/response-plan/files/guide-d.pdf