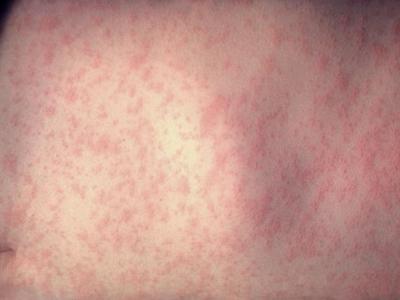

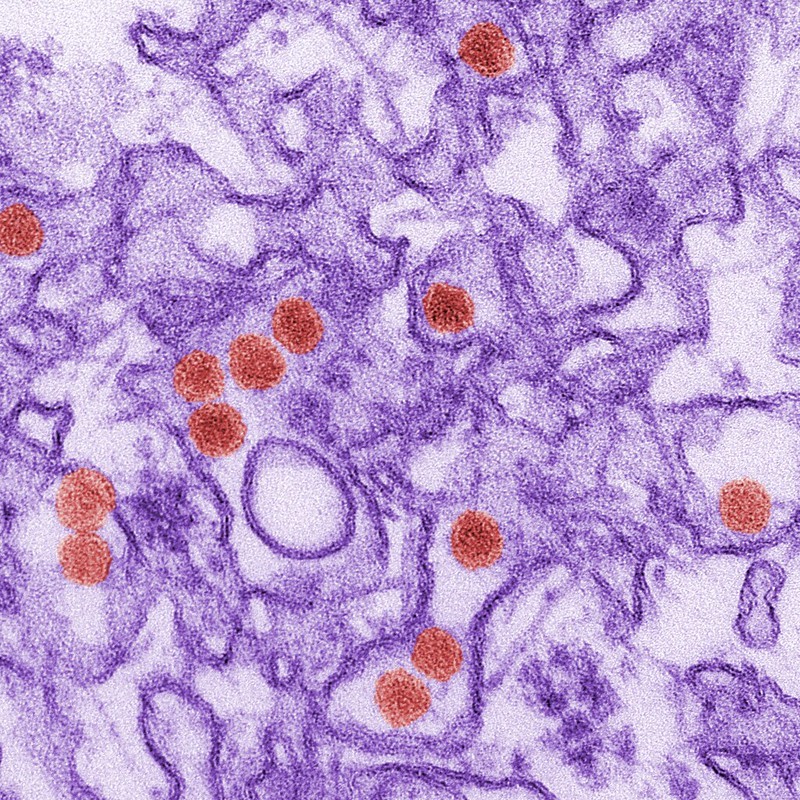

From its first human case in 1952 until just a few years ago, the Zika virus had affected relatively few people in Africa and Asia and was typically accompanied by mild symptoms: fever, body aches, rash, pink eye. Most people didn't have any symptoms.

But when it first appeared in the Americas in 2015 and was linked to congenital defects, including developmental issues and microcephaly (smaller-than-normal heads), affecting more than 3,700 newborns, particularly in Latin America, the world knew what Zika was.

Currently, there is no treatment or preventive vaccine for Zika virus infection, but as the disease's prevalence has faded, so has global concern. To spur the development of Zika medical countermeasures (MCMs), the University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP), the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), a task force of experts, and the World Health Organization (WHO) have created the "Zika Virus (ZIKV) Research and Development (R&D) Roadmap," a 10-year framework for optimizing research, diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines.

In the roadmap, experts outline 14 strategic goals, such as ensuring research tools are available, identifying funding sources, supporting novel therapies, and promoting vaccine development.

"We need to avoid an 'out of sight, out of mind' mentality. Just because Zika incidence is low now doesn't mean that this disease won't come back with a vengeance at any point in time," says Michael Osterholm, MD, PhD, CIDRAP director, and roadmap steering committee member. "The roadmap development process relies heavily on stakeholder engagement, which we hope will foster ownership of various goals and milestones in the roadmap."

Samba Sow, MD, MSc, director of the Center for Vaccine Development in Mali, says, "By highlighting key knowledge gaps, identifying strategic goals and milestones, and encouraging synergistic research and development activities, the roadmap will serve as a valuable tool to advance the existing complex field of Zika virus MCM research and stimulate overall investment in R&D and in implementation activities."

Starting today through Mar 26, the roadmap is open to public comment on the WHO website with an accompanying online reflection form. From there, it will be further refined and then published as a living document.

Zika's global but sporadic reach

Zika virus is one of 10 WHO priority diseases that include COVID-19, Ebola virus and Marburg virus, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and the unknown but probable "Disease X."

Unlike some diseases on the list, Zika can be found on most every continent, affecting a total of 87 countries and territories as of July 2019, according to the WHO. The massive 2015-16 outbreak in the Americas involved more than 700,000 cases.

Unlike some diseases on the list, Zika can be found on most every continent, affecting a total of 87 countries and territories as of July 2019, according to the WHO. The massive 2015-16 outbreak in the Americas involved more than 700,000 cases.

Zika infection, while normally mild, can lead to Zika congenital disease, whose symptoms may include microcephaly in infants. The WHO has also linked it to health problems such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, neuropathy, and spinal cord inflammation.

While the prevalence of Zika congenital disease has not been confirmed by the WHO, a 2018 study by researchers from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention looked at 1,450 children in US territories whose mothers had Zika during pregnancy. Of the children, 14% had birth defects associated with the virus and 6% had microcephaly.

People contract Zika infections primarily through bites from Aedes mosquitos, but it can also spread through sexual and vertical transmissions (from pregnant women to their fetuses), blood and blood products, and organ transplants.

This makes developing therapeutics and vaccines challenging, and to further complicate the process, Zika occurrences are unpredictable. Although fewer outbreaks are objectively a good thing, tasks such as testing possible MCMs or understanding complications of the disease can be stalled because of a lack of cases.

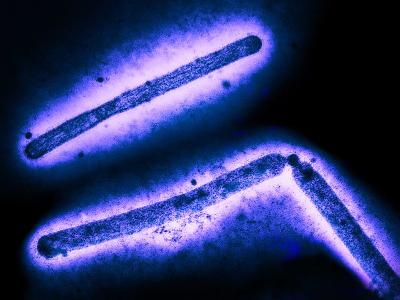

The disease's status as a flavivirus can also cause issues due to cross reactivity or similarity with other flaviviruses, which must be taken into consideration when developing vaccines.

Regarding diagnostics, Singapore is just one of the countries that can experience both dengue and Zika, says Yee-Sin Leo, MBBS, M Med, MPH, director of the country's National Centre for  Infectious Diseases and roadmap task force member. Because of the chemical overlap of the viruses that cause these two diseases, public health officials struggle tracking Zika, and Leo says polymerase chain reaction tests have generally been used only if there is sufficient clinical suspicion.

Infectious Diseases and roadmap task force member. Because of the chemical overlap of the viruses that cause these two diseases, public health officials struggle tracking Zika, and Leo says polymerase chain reaction tests have generally been used only if there is sufficient clinical suspicion.

Working through COVID disruptions

Leo and Osterholm are just two members of the international group working on the roadmap. The collaboration consists of 6 steering committee members from the WHO, UTMB, and CIDRAP; 22 task force members and subject matter experts; and 3 core CIDRAP researchers, all of whom were part of the CIDRAP team that helped create three other WHO roadmaps.

Steering committee member Alan Barrett, PhD, Sealy Institute for Vaccine Sciences director, WHO Collaborating Center for Vaccine Research director, UTMB professor, says that the roadmap has been crafted in an extremely collaborative environment, in part because of the solidarity COVID-19 has brought to the public health sphere as well as the fact that Zika is found around the world.

"It was great having the input of the task force members who came from different parts of the world. Their perspectives were very different based on their experiences and what they've seen of the disease, and that helps, I think, making—in my biased opinion—an excellent roadmap." he says.

The steering committee and the task force members met in Geneva in 2019 as the first of two in-person meetings. Then, when COVID-19 hit, the timeline got rearranged and digitized. While the roadmap was still able to come together, the next COVID-related challenge is to make sure it doesn't get lost in the pandemic noise.

As Jairo Andrés Méndez Rico, PhD, regional advisor of viral disease for the Pan American Health Organization and roadmap task force member, puts it, "The problem right now with the research is...Zika is very sporadic, so maybe it's a little loss of interest. And when, of course, you have COVID for more than 1 year, everyone's slowly thinking and talking about COVID, and the funds are going to COVID. Everything is very, very difficult to keep moving at the same speed with other things like Zika right now."

Fortunately, there is one potential advantage to COVID-19: It's forcing innovation. Because of that, perhaps the road to R&D can be disrupted for the better.

"I don't think it's possible to have a sensible discussion at the current time until the pandemic is finished, because the pandemic is teaching us so much about emerging disease as we go forward," Barrett says. "Look at the way vaccines have taken off, and the mRNA vaccines. They were sort of discussed when [COVID-19] arrived, but look how fast we've made them."

"I don't think it's possible to have a sensible discussion at the current time until the pandemic is finished, because the pandemic is teaching us so much about emerging disease as we go forward," Barrett says. "Look at the way vaccines have taken off, and the mRNA vaccines. They were sort of discussed when [COVID-19] arrived, but look how fast we've made them."

Roadmap builds on past research

The Zika virus R&D roadmap has 14 strategic goals and 70 total milestones, with the earliest one occurring in 2024. End points include assessing and developing different-use diagnostic tests, pursuing regulatory approval of therapeutic candidates that have cleared phase 1 and phase 2 trials with special notice toward neonates, and the creation of sufficient vaccine candidate supplies ready for phase 3 or phase 4 trials when outbreaks occur.

Researchers won't be starting from scratch in every area. Vaccines published a roundup of Zika vaccine candidates in June 2020 that reported seven in phase 1 clinical trials and one in phase 2. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published a similar article in November 2020, but it looked at therapeutic candidates, noting that one type, tetracycline antibiotics, may be easier to move to clinical trials because the US Food and Drug Administration has already approved it.

The experience that Zika outbreaks have provided researchers is no small matter, either. In Brazil, flaviviruses such as dengue and yellow fever are endemic, so when Zika virus broke out across the country in 2016, public health officials were able to adapt dengue surveillance methods to Zika, says Méndez Rico.

"Nevertheless, we still need more information regarding, for instance, the dynamic of the virus, and we have to learn a bit more about the technical patterns," he says. "We still need to know how to work within the serology, because serology is a tool, an important tool, but we can't apply it for the same flaviviruses."

Protecting the vulnerable

Part of what makes Zika such a priority is that not only does it make an already vulnerable population—pregnant women and children—even more vulnerable, those ramifications weren't noted until the mid-2010s. Leo believes that the risk of initial clinical vaccine trials in pregnant women is still too high, adding that because Zika can be transmitted sexually, it's worth vaccinating mass populations.

"No one predicted that Zika would come back at that larger scale," Leo says. "And not only that, but Zika was being seen for a long period of time as a disease that is very mild in clinical  consequences [but now it has] caused such a drastic, traumatic outcome in the recent episodes, where we see so many of the infants being born with abnormalities. We can't really predict how the virus will behave in the future."

consequences [but now it has] caused such a drastic, traumatic outcome in the recent episodes, where we see so many of the infants being born with abnormalities. We can't really predict how the virus will behave in the future."

Besides R&D, the roadmap mentions that other efforts are needed such as vector control, contraception access, and community engagement. Even though the document does not delve deeply into these initiatives, their very mention underscores the roadmap's importance.

"The most important part of the roadmap is starting the conversation," Méndez Rico says. "We know each other, so in the end, I think it was a very, very good work—how to finally make an agreement of what it is we really have to do and what we have to know in the next years."